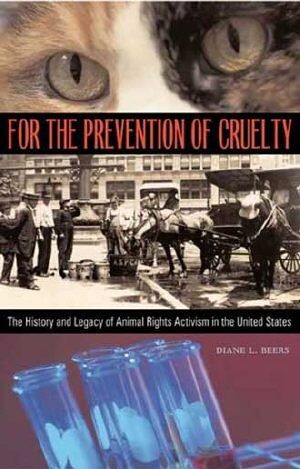

| FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY: THE HISTORY AND LEGACY OF ANIMAL RIGHTS ACTIVISM IN THE UNITED STATES By Diane L. Beers Swallow Press $19.95, 368 pages |

Though Diane L. Beers begins her history of animal advocacy in 1641, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony adopted its "Body of Liberties" (which included provisions against cruelty toward animals), she is silent about the treatment meted out a few months later to Granger's favored creatures. The tradition of animal advocacy in this country runs parallel to a history of flagrant abuse. Homo sapiens have exploited other species for food, clothing, experimentation, and entertainment on such a massive scale and with such indifference to their agony that it seems perverse to apply the term "brute" to anyone but a human being. "For the animals it is an eternal Treblinka," wrote Isaac Bashevis Singer, a vegetarian who knew that cruelty to other species existed long before the Nazi death camps. Yet Singer did not invent vegetarianism, and opposition to fur and circuses goes back more than a hundred years.

Beers's book documents a continuity between the concerns and tactics of 19th-century animal advocates Henry Bergh and Caroline Earle White and today's campaigners against cruelty in laboratories, pounds, and factory farms. She uses the term "animal advocacy" to cover the entire spectrum of activism - from animal-welfare proponents who believe in human preeminence but stress our responsibility to minimize the suffering of "lesser" species, to animal rights radicals who, rejecting traditional anthropocentrism, insist that no species can be privileged when it comes to suffering. Beers claims the origins of organized animal advocacy are rooted in the abolition movement, and shows how other social-justice efforts, such as women's suffrage, child protection, temperance, and labor reform, attracted some of the same supporters.

Like other causes, animal advocacy has always been subject to a tension between accommodationists and revolutionaries. Just as civil rights were advanced through the combined, often philosophically conflicting, efforts of the conservative National Urban League and the militant Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, so, too, have the interests of non-humans been represented by both the American Humane Association, which collaborated with railroads and meatpackers to improve conditions for cattle before their slaughter, and the American Anti-Vivisection Society, whose motto Non facias MALUM ut inde fiat BONUM (You cannot do EVIL that GOOD may result) underscores its ethical fundamentalism. In recent years, animal advocates have formed alliances with environmentalists, but the two have also clashed when the interests of entire ecosystems seemed at odds with those of individual organisms.

Beers reviews the principal successes of animal advocacy: 1866, the first cruelty conviction; 1871, the first federal cruelty statute; 1958, the Humane Slaughter Act; 1966, the Laboratory Animal Welfare Act; 1972, the Marine Mammal Protection Act; 1973, the Endangered Species Act. She becomes most animated and detailed in the period following World War II, when prosperity and consumerism intensified both the assault on animals and efforts to protect them. Noting that Peter Singer's eloquent Animal Liberation inspired a new era for advocacy, Beers halts her history in the year of its publication, 1975. For discussion of dramatic developments of the past three decades (the elimination of dissection from medical- school curricula, banning of pâté de foie gras in some cities, Animal Liberation Front's guerrilla raids on abusive laboratories, adoption of "no-kill" policies by municipal pounds, campaigns against fur, the emergence of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals as leading scapegoat for those contemptuous of the rights of goats, even the NBA's adoption of a non-leather basketball), readers will have to look elsewhere.

Passion for the rights of animals drove Bergh to confront armed hunters and White to attempt citizens' arrests of drivers who abused horses. Beers is dispassionate and informative about a subject that remains as timely as Whole Foods' recent decision to cease stocking live lobsters. She is particularly attentive to the sociology that has been driven by affluent white Northeasterners, and she notes that, until recently, though women comprised the majority in animal-advocacy groups, the leadership has been male. (Opponents have attempted to stigmatize them all as "zoophilic psychotics.")

Rational argument, by Peter Singer, Rachel Carson, and others, has done much to change the way Americans relate to other species. But to reach hearts - and stomachs -as well as minds, it takes more than a syllogism proving that meat is murder. Beers describes how humane books by Jack London, Mark Twain, and Anna Sewel (Black Beauty) seized readers' imaginations, but she is silent on the effect that Hollywood has had on attitudes toward animals. Bambi has done more to discredit hunting than bungled blasts by Dick Cheney. Gorillas in the Mist, Free Willy, Babe - concern for the rights of animals is not just Mickey Mouse.