Another train ran off the rails last month in San Antonio. One television station took a camera up in a helicopter, so for almost an hour we had wonderful bird’s-eye views of derailed boxcars on the ground. The strangely fascinating images of this train accident suddenly reminded me of a conversation four months ago. My friend Jim and I were talking about new developments in architecture. I was extolling the superiority of European design in general when Jim interrupted in an irritated tone: “You love buildings that look like train wrecks.”

My response was a barely audible “Hmmm.” I recognized the kernel of truth in his accusation. Poor Jim — having to lead me back to the safe world of xyz and its Cartesian coordinates, where everything gets plotted on imaginary x, y and z axes. It’s a design environment in which armies of happy CAD monkeys impose rectilinear logic on everything. In that world, draftsmen always make the most efficient use of 4 by 8-foot plywood panels, and every corner meets at 90 degrees. I totally understand orthogonal language but I know that its spatial definitions are mere constructs.

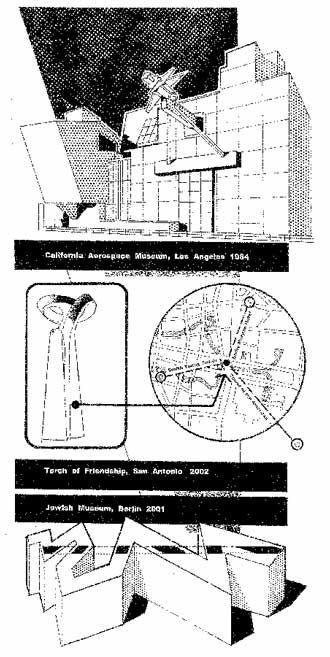

The televised train wreck was shown from new angles as the helicopter hovered overhead. The zigzag line of boxcars looked nothing like any building I knew. Well, except maybe Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum* in Berlin. Some people see a lightning bolt in its zigzag plan. Was Jim referring to this iconic building? On TV, more views of the train wreck. One boxcar was rammed into the side of a small house. OK, maybe Jim had seen pictures of Frank Gehry’s notorious house* in Santa Monica, that famous blip from 1978 that infuriated so many people. (Yes, that was 28 years ago!)

I’m not sure why deviations from orthogonal construction whip some people into a froth. It’s one thing if your house is designed to be perfectly square and your contractor builds rhomboid rooms and crooked corridors. I see how that’s a problem.

But what about buildings designed outside the xyz envelope? Sometimes there are legitimate reasons to rotate grids, to set building elements at disquieting angles. Something other than artistic whim or attention-getting strategy might generate such a building. It could be a special condition that produces oblique architecture, a unique circumstance of site or program. Whatever it is, I am sure it will antagonize someone.

I’d like to cite a significant local building outside the xyz box, but I can’t find one radical enough. Instead I will focus on two large sculptures to illustrate xyz and non-orthogonal conditions.

There is probably no better example of a Cartesian xyz sculpture than “Asteriskos,” the Tony Smith steel sculpture. It was a memorable HemisFair landmark in 1968. After it was rescued from the scrap-metal pile it was relocated to the McNay Art Museum grounds in 1970.

The Torch of Friendship by Mexican sculptor Sebastián is Asteriskos’s non-orthogonal counterpart. Installed in 2002 where Alamo and Commerce Streets meet, it is a towering red-orange exclamation point that brings an omnidirectional dimension to this key location. Essentially a continuous, ribbon-like, painted metal construction, the sculpture functions as two conjoined identities, one belonging to the ground plane and the other to the sky. Its tapering stable legs anchor it firmly into the fixed street grid. On top, the suggestion of a circular crown is unmistakable, eliciting a fluttering fabric or rotating riata. The implied motion seems appropriate at this vehicular turnaround, where this sculptural gesture up in the air echoes and reinforces the counterclockwise traffic pattern below.

A pedestrian approaching the sculpture from any direction cannot fail to link it visually with the Tower of the Americas, the Smith Young Tower, and the neo-Gothic turret of the Emily Morgan at numerous sidewalk station points. These references provide nudges along expansive and exhilarating lines of movement apart and free from the rectilinear ground plane.

Donald Kunze, a professor of architecture, decries the predominant cultural xyz bias so deeply ingrained in us because it dulls our ability to know the world in genuine and direct sensory experiences. By grade-school age we’ve learned to impose rectangles on the natural world at the expense of appreciating its true forms and understanding its complex order (which is certainly not orthogonal). Xyz is convenient when laying out townships and residential plots, or turning trees into stackable lumber, but it will always be an order imposed by convention. A map of the U.S. with state lines shows the prevalence of imaginary straight lines. In contrast, Mexico’s state boundaries usually follow rivers or mountain ridges. The same is mostly true for regional divisions in countries that were never part of the British Empire. Open your atlas and see.

| Here are three websites to explore extra-orthogonal architecture: Scrapbookpages.com/Berlin2002/JewishMuseum Greatbuildings.com/buildings/Gehry_House.html Morphosis.net |