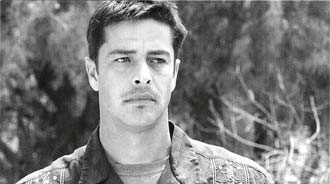

| Mexican border agent Adam Fields (John Carlos Frey) treads uneasy lines — geographical, cultural, and legal — in The Gatekeeper |

In Preston Sturges' Sullivan's Travels, a successful movie director strays beyond his privileged enclave in Hollywood to learn about the misery and desperation of ordinary Americans during the Depression. In Black Like Me, John Howard Griffin darkens his skin chemically in order to experience what Jim Crow meant to its victims. And in Gentleman's Agreement, Gregory Peck gains personal acquaintance with anti-Semitism by pretending to be Jewish.

In The Gatekeeper, Adam Fields (Frey) undergoes a journey, incognito, that opens his eyes to how the other half lives. But that was not his intention, and, as a light-skinned Latino, he resisted acknowledging he was part of that other half all along. A border agent assigned to guard California against unauthorized entry from Mexico, Fields is overly zealous about his job. "We must protect ourselves from illegal immigrants," he insists in a propaganda video he makes on his own time for a group of isolationist vigilantes. "We are being overrun by Mexicans."

Denying his own Mexican origins, Fields is intent on stanching the flow of human traffic over the border he has sworn to secure. Slipping undercover, he stages a scheme to lure immigrants into an ambush. Pretending to be an alien named Juan Carlos Mendoza, Fields crosses into Tijuana and hires a coyote to smuggle him, along with about a dozen others, back into California. The plan for his vigilante confederates to intercept the smuggled party is bungled, and Fields finds himself trapped in the plight of an undocumented Mexican. Brought at gunpoint to a secluded farm in central California, he and the other migrants become virtual slaves to a criminal methamphetamine operation. When Fields attempts escape, he is shot in the leg as a warning to the others. At the outset of The Gatekeeper, Fields repudiates his dying Mexican mother, but by the end of his ordeal, he has grown to recognize his ties to his fellow human beings. In the final frame of the film, Fields grasps the hand of an orphaned Mexican boy, reconciling himself with his own rejected childhood identity.

The Gatekeeper is an impassioned polemic against demonizing the 11 million people, 80 percent of them Mexican, who have illegally crossed the porous borders of the United States. Perhaps not since El Norte has a feature film so graphically portrayed the hardships endured by those desperate enough to attempt a breach of this country's southern boundary. It draws the viewer into a daily drama of exclusion and exploitation that most citizens of the United States are content to ignore. In the anti-Mexican Latino Adam Fields, Frey provides an effective guide for leading the North American viewer across the border from apathy (or even enmity) to empathy.

| The Gatekeeper Writ & dir. John Carlos Frey; feat. Frey, Michelle Agnew, Anne Betancourt, Joel Brooks, Joe Pascual, Kai Lennox, J. Patrick McCormack, Tricia O'Kelley (R) |

Like a prince who discovers that his covert jaunt has gone too far and he is caught in a pauper's world, Adam, a true American, insists to his Mexican companions: "I don't belong here." Nobody belongs in a forced-labor camp, but, suggests the film, if anybody does, so do we all. •

A CONVERSATION WITH JOHN CARLOS FREY

By Steven G. Kellman

Producer, director, writer, and star of his first feature film, The Gatekeeper, John Carlos Frey is also overseeing its distribution and promotion. He spoke to the Current by phone from Las Vegas, where his film is being shown. Frey visits San Antonio this week for Q&A sessions following the Friday, August 1 and Saturday, August 2 evening screenings of The Gatekeeper.

Born in Tijuana, Frey grew up in San Diego, a half mile from the border, where apprehensive aliens were as abundant as the Border Patrol agents out to apprehend them. Although his father was Swiss, his mother was Mexican, and he remembers how once, having neglected to carry proper identification, she was temporarily deported to Mexico. As a child, Frey did not embrace his Latino identity: "I wanted to pass, and I did."

Frey never intended to direct his own screenplay. "I tried to sell it for three years but couldn't get anyone on board," he says. Theatrical distribution of The Gatekeeper comes now at the end of an arduous six-year process. Frey raised the scant $200,000 he used to make his film and, to reduce costs, took on the roles of director and lead actor. "It was an excruciating experience. I will hopefully never have to do this again."

Frey shot his film in sequence, and the process made him as haggard as his tormented character, Adam Fields, was supposed to be. "I wish I had enough financing just to direct," Frey says.

However, because his minuscule crew was not intrusive, the United States Border Patrol was very cooperative and allowed Frey to shoot in restricted areas and to ride with its agents as part of his research. He interviewed undocumented immigrants and reviewed reports from the Drug Enforcement Administration. The meth lab operation in The Gatekeeper is drawn from DEA case files, and what the film calls the National Patrol is modeled after an actual vigilante group called the American Patrol.

The Gatekeeper has been wowing crowds at film festivals and earning the admiration of Border Patrol agents and Latino leaders. It has also provoked hostile letters and even a veiled death threat against Frey. Asked whether he expects his film will have an effect on immigration policies in the United States, the producer-director-writer-actor is loath to present The Gatekeeper as a political document. "It's just a movie," Frey insists. But he clearly also has ambitions beyond just entertainment.

"I hope the film exposes an issue that is underrepresented in the media," he says. "I hope it can raise the awareness of the American people of who these people are and what they endure." •