In America's wilderness - solace, sonnets, and some really bad corporate behavior

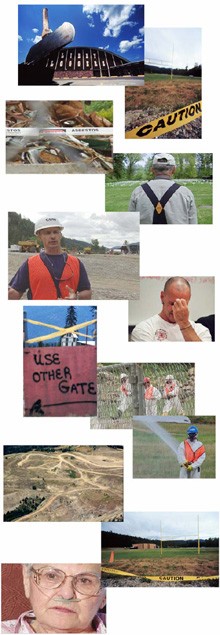

| Scenes from America, gothic: Libby, Montana, pop. 2,400, was home to a W.R. Grace vermiculite mine that so contaminated the town with asbestos more than 10 percent of its residents have died from related diseases. In 1999 the EPA began a belated and costly cleanup. Some of the Libby vermiculite ended up at San Antonio's Texas Vermiculite. |

The real-life cast of American Values is deliberately diverse, challenging Outside and Adventure magazines' portrayal of nature as the domain of Tactel- and Lycra-clad Yuppies. Native Americans, Latinos, African Americans, and the children of Cambodian refugees reminisce about their experiences in wilderness and how important open spaces "as free from human intervention and oversight as possible" are to their identity and quality of life. Cheryl Armstrong, whose father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were hunters and fishermen, talks of bringing urban youth of color to the woods. Donald Rodriguez recalls that he saw his father "in another light" on the family's annual trip to Yosemite; now he shares that bond with his two young sons. Alaskan Faith Gemmill remembers hunting in the mountains as a child, wrapped in caribou hides. At the end of its quiet, captivating hour, American Values has redefined wilderness as neither a commodity nor a luxury, but a public good that belongs to us all.

High Plains Films, now more than a decade old, makes documentaries that explore the relationship between nature and society, which requires confronting irony on a regular basis. Its 2004 feature, Libby, Montana, shows how scenic isolation can be costly. In the sparsely populated West, W.R. Grace operated a vermiculite-mining operation that employed a significant portion of Libby's 2,400 citizens. The ore was separated and refined at the mine and shipped to Grace facilities nationwide to be processed into potting-soil additive and the popular insulation filling Zonolite. The town's second-greatest natural resource after lumber, Libby vermiculite contained unusually high amounts of tremolite asbestos, a highly toxic form of the mineral because it easily becomes airborne in small particles. Once inhaled, these particles become imbedded in the lung's lining, which forms copious scar tissue in response. Grace executives sat on Libby's school and hospital boards, and attended church alongside employees who were gradually dying of asbestosis and mesothelioma, a type of lung cancer caused by exposure to asbestos.

As hundreds of men became ill - at last count more than 10 percent of the town died from related causes - Grace was able to rely on Libby's natural insulation from the flow of information and knowledge. As early as the 1950s, before Grace purchased the plant, the government had notified the mine that its vermiculite posed a health risk. Company documents from the '70s , when Grace owned the facility, show that the East-Coast company was aware that it was incurring an immeasurable liability by not notifying its employees of the risk. One man recalls that after the annual company physical, the report always came back "no change," which made it all the more shocking when an independent, out-of-town doctor told him he had five to seven years to live because so little was left of his lungs.

Earl Lovick, manager of the Libby plant, in many ways epitomizes Hannah Arendt's "banality of evil." During legal testimony, Lovick admits that Grace had a responsibilty to its employees; but later he tells his inquisitor that they didn't tell the men not to touch a red-hot stove, either. That rationalization might have been more compelling if the filmmakers hadn't recorded former union president Robert Wilkins recalling how he learned from an out-of-town remediation crew that came to clean up a spill that tremolite is asbestos. When Wilkins confronted Lovick, he tells the camera, Lovick spread his hands wide and said, "Bob, I thought everybody knew that!"

Grace certainly knew, and it knew that the tremolite, freed into the air by strip mining and processing, was killing its employees. In 1969, Lovick possessed a document showing that 42 percent of its 10-year employees were dead or dying of asbestosis or mesothelioma, and 92 percent of its 20-year employees were meeting the same fate. Lovick himself had surgery to address his asbestosis, demonstrating conclusively that nothing is as valuable as information - information that Lovick nonetheless withheld from the men whose families he saw daily on the streets of this tiny town.

| Actor Christopher Reeve narrates American Values, American Wilderness, which presents a wide variety of people talking about their love of untrammeled nature and the relationships and identity fostered in the wild. |

But Libby's isolation didn't protect the rest of the country from its deadly export. The EPA has cleaned up a handful of the 240 sites that received and processed vermiculite from Libby. In San Antonio, more than 103,000 tons passed through the Big Tex Grain Co. site (formerly Texas Vermiculite) on the banks of the San Antonio River just south of Blue Star, but no data has been made available on the current level of contamination, if any `see related story, page 8`.

Libby's remoteness also tells a cautionary tale about political power, which is exercised through money and proximity. W.R. Grace executives, now facing federal indictments for their actions and inaction in Montana, are accused of obstructing the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health when it wanted to study the conditions at the mine in the '80s. At that time, company head Peter Grace chaired President Ronald Reagan's Grace Commission ("the President's right hand," is how Wilkins describes it), charged with finding ways to downsize the government. Thanks to numerous environmental-pollution suits, Grace's net profits dropped almost 90 percent during the '90s, it filed for bankruptcy in 2001, and now the political tide has turned against it. But 20 years would have made a significant difference in the life and health of the town's surviving residents.

If the political pressure to prosecute Grace's executives to the full extent of the law persists, it will be due in part to this deeply moving film, which won numerous awards at festivals last year. Many critics have praised the "objectivity" of filmmakers Doug Hawes-Davis and Drury Gunn Carr; what they mean is that the directors let the headlines, residents, and Lovick tell the story. This time-tested documentary technique seems fresh in the wake of last year's much-more-publicized and vocally political Fahrenheit 9/11, but at its root is the recognition that Libby, Montana isn't a red-state or blue-state story. It is a story about American democracy and American capitalism, and the battle that must constantly be waged to keep the latter from consuming the former. •

American Values, American Wilderness will air on PBS this summer. Check local listings for showtimes. Libby, Montana is available from High Plains Films at highplainsfilms.org.

By Elaine Wolff