A local volunteer delves into the (growing?) SA homeless scene

“Welcome to the Streets”

By Liz, 18You can feel your skin harden,

You can feel the emotions fading,

That’s what they do to you,

The Streets.

The smells are the same,

They are the constant reminder of how low you have actually sank.

You’ve become the bottom feeder, the one that has to be tough.

I’ve lost all stability in my life

My home, family, friends ...

I want it all back now.

I want my life back.

This is my home and life.

So, to a passerby who looks down at me with their nose up,

I hold my own head higher

And say with a smile:

“Welcome to the Streets”

The 18-year-old woman who wrote this poem expresses feelings that many of the chronic homeless have about life on the streets early in their experience. Most, however, either don’t remember (or don’t want to recall) the brutal reality expressed in these lines, and have psychologically acclimated to their harsh surroundings.

According to San Antonio homeless advocates, the chronic homeless are extremely difficult to help, due at least in part to widespread mental illness and drug dependence. Pastor John Flowers of Travis Park United Methodist Church — which runs the Café Corazón homeless-outreach program where I volunteer weekly — says that about one-third of the homeless nationwide are chemically addicted, one-third have been diagnosed as mentally ill, and there is substantial crossover within these groups. He sees these numbers reflected locally.

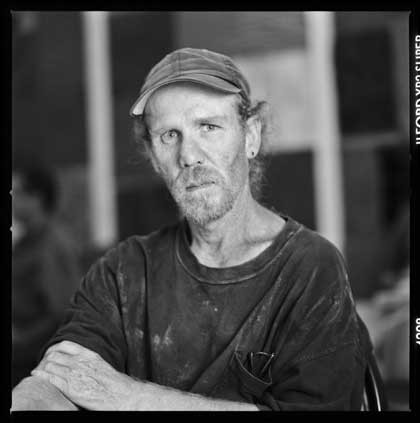

| Charles Davis has been coming to the church's day center since he came to San Antonio five months ago. Davis, who has been on the streets since he was 17, says that the day center has helped him get his Social Security card and gives him a place to get off the streets. |

“These populations are very tough to treat,” says Flowers. “Mainly because they have become accustomed to the lifestyle.”

Public concern and public policy have long been focused on the antisocial behavior of the chronic homeless. Last year, the San Antonio City Council passed an ordinance that in effect, opponents argue, criminalizes homelessness, with penalties of up to $500 for aggressive panhandling, sleeping in public, urinating in public, and camping without a license. As of January, nearly 500 people were cited for violations. In large part because of this law, San Antonio was ranked as the 13th “meanest city” nationwide by the National Coalition for the Homeless. A dubious distinction, but SA’s not alone: Three other Texas cities finished in the top 15.

“Jim,” who has spent many years on the street, personifies the prevailing controversy over chronic homelessness. Though not diagnosed as clinically schizophrenic, he appears to have two distinct personalities. When sober, he seems extremely kind; I have observed him making thoughtful gestures toward his friends. After drinking, though, his other side takes over. Under chemical influence a few Saturdays ago, he interrupted a church wedding and had to be escorted out by the police. He expressed remorse about his actions the next day, after sobering up and learning of the incident, which he didn’t remember.

Even an eternal optimist would find it hard to argue that all the homeless can be rescued. There are many, however, like the poet Liz, who are teetering on the edge and can be helped.

Liz remained eerily calm while telling her horrific story. She was raised in the South by an abusive, drug-addicted father who forced her to engage in illegal activities to support his habit, and has mental-health problems, including diagnosed paranoia and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“I created problems at the last shelter and was asked to leave,” she said, when I asked why she wasn’t in a shelter or attending school. But, she adds, “I plan on getting my GED and eventually going to college.”

Travis Park Day Center Manager Gene Hauser said that to solve the problem of homelessness, we need first to identify why people become homeless. Hauser said the homeless face a number of problems, including, but not limited to: mental-health issues and substance abuse; lack of financial resources and stability; lack of affordable housing; and legal problems.

“Although the City, under the Department of Community Initiatives, does a tremendous job, there simply aren’t enough funds available for mental-health care,” he said. “Several years ago, there were major Medicaid cutbacks in psychological-social rehabilitation, and this caused a bad problem to become worse.”

This year, the National Alliance on Mental Health ranked Texas 47th in mental-health funding; the state spends a paltry $39.02 per capita.

“We don’t have sufficient funds to provide mental-health care and counseling,” laments Clemencia Prieto, a community action manager with the City. Government reports back her claim: According to the National Mental Health Association, Texas agencies were forced to reduce their budgets after the Texas Legislature made dramatic cuts in mental-health funding during the 2003 session — a move advocates for the mentally ill said would result in more than 25,000 people losing state-assisted mental-health care.

Dennis Maricelli, the I.D. recovery coordinator at the church, sees another serious problem on the horizon. He posits that “The homeless population in San Antonio is going to increase dramatically in the near future due to the loss of housing subsidies for Katrina victims. We’re totally unprepared for this event.” `For more on that topic, see “Life on the brink,” July 5-11, 2006.`

In addition, according to Prieto, the number of homeless youth has doubled since November 2005. So far, there’s only speculation about the reasons for the dramatic increase. One theory she offered is that, due to limited foster-care resources, children are seeking refuge on the streets.

“Mike,” who fidgeted at first and seemed hesitant to speak with me, quickly warmed up, seemingly willing to discuss his plight. He smiled frequently and expressed pride in having helped others, but said that he desperately wanted to leave the streets and have a place of his own.

| Sharon Adkins has been homeless for two years and is now a member of the Travis Park United Methodist Church and occasionally volunteers at the church's day center for the homeless. |

“I have had numerous construction jobs, but just couldn’t stay employed,” he said. He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and had been taking lithium, but isn’t taking the medication now. His name, he said, was put on a waiting list for mental-health care. “I can’t remember how long ago it happened,” he said, “and I’m not sure if I’ll get help soon.”

The 2-1-1 Texas/United Way Help Line lists organizations that provide counseling on a sliding-fee scale. The Family Services Association on San Pedro has a waiting list of “two months or longer.” Jewish Family Services, said it was unable to see anyone in the foreseeable future. A call to the Mental Health Association, an organization that provides a list of mental-health providers in San Antonio, yielded a recording saying that they had only part-time staff and that it would take a while to return phone calls.

Many people enter the streets chemically addicted, and the desire to break away from the pain through drugs and alcohol can exacerbate their situation. Yet often, when they go for help, none is available. According to Dr. John Roache, a professor of psychiatry specializing in addiction issues at the University Health Center, there’s “very little municipal and state support for treatment programs.”

Prieto echoed that sentiment.

“There are an insufficient number of detoxification facilities and alcohol-abuse treatment providers in the city of San Antonio to deal with the demand for services,” she said.

Dr. Christopher Wallace, Roache’s colleague and another addiction expert, said that “San Antonio doesn’t even have a combination detoxification and rehabilitation center,” something, he said, that is desperately needed in this area.

Obviously, financial hardship is a major cause of homelessness. The minimum wage — the rate earned by many of the homeless when they’re able to find work — hasn’t risen in nearly 10 years and, adjusted for inflation, is 40 percent less than in 1968. Those earning minimum wage or just above minimum wage find themselves closer to homelessness than any other group because they’re unable to save for the proverbial rainy day.

Recent attempts to raise the federal minimum wage have proved futile. When, in May 2005, U.S. Senator Ted Kennedy and Representative George Miller proposed a modest increase of $2.10 phased in over a period of two years, the proposal was quickly defeated by the Republican leadership — as were three similar proposals during the prior session of Congress. If lawmakers don’t pass a new minimum wage before George Bush finishes his term, workers will have gone a record 11 years without an increase, eclipsing the nine-year record set during the Reagan administration.

“This is a definite problem,” Hauser said. “If I earn minimum wage, how can I afford to pay rent, let alone other expenses?”

Even a night’s respite from the streets can drain a few hard-earned dollars. An eight-hour shift at a minimum-wage job pays about $40 before taxes. A night at one of the cheapest hotels in town, The Traveler, costs $28, leaving barely enough for food.

Fourteen states and more than 125 municipalities have countered the lack of federal support for a minimum-wage increase by enacting “living-wage” ordinances. These laws, which are indexed to cost-of-living increases, require that employers — particularly those who profit from government contracts — pay several dollars above the federal minimum wage. Texas, however, due to pressure from the hospitality lobby and concomitant campaign contributions, not only refuses to consider a living-wage law, but is one of only eight states to ban city-level living-wage laws.

“Every job that pays less than $8.20 an hour — the absolute minimum needed to pay the bills — contributes to the plight of homelessness,” Pastor Flowers said.

Legal problems can haunt the homeless long after they have paid their official debt to society by serving jail terms, parole, and probation. Anyone convicted of certain sex, violent, or drug felonies is automatically excluded from federally financed housing programs, said Janice Wehrman, the City’s community initiatives homeless coordinator.

“There’s no system to find housing for this population. If they’ve been convicted of a methamphetamine crime, a violent crime using a weapon, or a sexual offense, then they’ve lost all rights to public housing,” she said. “This is one of the main reasons why we see an overrepresentation of people with criminal backgrounds living on the street.”

Overcoming any criminal background can be challenging. Rob, a 28-year-old ex-felon, is clean-cut (the only unconventional aspect of his appearance is the tattoos covering both arms), but said he still has trouble getting work.

“The main problem is my criminal record,” he said, referring to a five-year-old domestic-violence conviction. “Few employers are willing to give me a chance. Once they hire me, they’re always happy with my work performance — the only problem is lack of opportunity.”

Though convincing politicians to provide sufficient resources for combatting homelessness seems like a daunting-enough task, even more challenges lie ahead. “We’re seeing drastic changes in the homeless population,” Wehrman said. She added that as of April 2006, families accounted for nearly 40 percent of the homeless population, and more than two-thirds of those were headed by single parents. One of the main reasons for this increase stems from changes in national attitudes toward social programs following the 1994 Republican Revolution, and continuing through the Bush Administration. A program that resulted from these changes, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, allows enrollees to receive assistance for a maximum of just five years, with few exceptions. Wehrman said that we’re now seeing these clients fall into homelessness due to their inability to get a job that would enable them to pay such expenses as childcare and rent.

Flowers summed up his view of the state of affairs: “If we don’t find reasonable intervention behaviors for dealing with chemical addiction and mental health, the homeless problem will neither be eradicated, nor lessened.”

Jim shares Flowers’s tepid view of the future.

“If I could somehow come clean,” he said. “I believe half the people on the streets would consider it a miracle and follow my path.” Lowering his eyes, he added, “But I just can’t seem to do it.”

Ron Palermo is a weekly volunteer with Corazón Ministries, a Christian, nonprofit homeless-outreach program at Travis Park United Methodist Church.

This is the second in a two-part series concerning S.A.’s homeless population. Last week, the Current looked at Katrina victims who may soon become homeless because of a loss of FEMA subsidies in “Life on the brink,” July 5-10, 2006.