Emilio Ledezma and the SA Aztecs refuse to give up on a dream

A couple of years ago, the San Antonio Aztecs traveled to Alvin for a semi-pro football game. The driver of one of the team’s vans lost his way en route to the stadium, and at game time the Aztecs had only 10 players available. Never a good thing in a sport that requires you to put 11 players on the field at all times.

Emilio Ledezma, the team’s coach, was well into his 40s by this point, but he found an extra pair of shoulder pads and an unclaimed helmet and suited up for the game, which the Aztecs won in a rout. Ledezma doesn’t make a habit of this kind of 12th-man heroics, but he always looks like he’s itching to run onto the field and piledrive a running back into the turf or lay a nasty block on a blitzing safety.

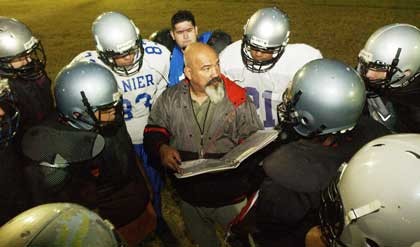

| Emilio Ledezma, head coach of the San Antonio Aztecs, dissects a new play for his team. (Photo by Mark Greenberg) |

As the founder, coach, organizer, and surrogate father to this team of gridiron moonlighters, Ledezma, 44, is the most extreme example of the semi-pro football ethos. Short and stocky, with a shaved head, dark mustache, and wild, gray goatee, Ledezma conveys hard-scrabble intensity. With his refrigerator frame and pitbull tenacity, you can easily imagine him being a ferocious tackler in his heyday. And nothing delights him more than watching one of his defenders lay a solid hit on someone — even if it’s a teammate in practice.

Semi-pro football is a subculture built on people like Ledezma, athletes who refuse to give up the game when the scholarship offers don’t arrive in the mail and the scouts don’t know your name. The rare occasions when semi-pro ball is written about or discussed, it’s inevitably said that these players play “for the love of the game.” How else do you explain the great lengths these warriors travel for the tiniest crumbs of glory? For starters, “semi-pro” is a misnomer. It suggests that players get paid to play (they don’t), that their equipment is provided for them (it isn’t), and that they practice and play at first-rate facilities (hardly, unless middle-school fields count).

Nonetheless, there is precedent for semi-pro players making a jump to the summit of pro football. Before Johnny Unitas rewrote the NFL record book with the Baltimore Colts, he played semi-pro ball in Pennsylvania for $6 a game.

With the inevitable personnel turnover that comes with semi-pro ball, Ledezma defines the Aztecs more than any single player because you sense that he coaches this team because he simply can’t imagine not doing it. As if the Aztecs don’t occupy enough of his time, he also runs a youth football league and trains boxers. One of his Aztecs assistant coaches, John Jutez, says with affectionate sarcasm: “Emilio’s out of control. If he can find a way to do something without getting paid for it, he will.”

Ledezma’s dedication is on full display as the Aztecs take the field for their final pre-season scrimmage on January 28 against their crosstown rivals, the San Antonio Riders. The team begins its regular season on February 25, and the coach has high hopes for this year’s squad. About 60 spectators are in attendance at Little Cowboys Stadium, a spartan field on the South Side. The scoreboard doesn’t work, the coaches generally have to guess how much time is left in a quarter, and the officials spend part of their time instructing the baffled linesman on where to move the first-down chains.

Gathering his squad in a sideline huddle, Ledezma says, in his perpetually hoarse shout, “No fighting guys. Let’s keep it straight up. If you wanna hit somebody, use your pads.”

Because they’re still paying equipment fees for the 2006 season, the Aztecs players are a motley, ragtag lot. Some players wear blue jerseys, while others are in black, and a few wear yellow or white. All the key players are here, guys best known by their nicknames: Smoke, Lee-bo, Big Chris, Double D. On the sidelines, 33-year-old Joaquin Hernandez sits next to players a decade younger than he is, and shakes his head with wonder at his own attempt to reclaim high-school glories after 14 years away from the game.

| The Aztecs celebrate a tough win over the San Antonio Riders. (Photo by Gilbert Garcia) |

Ledezma put this team together, designed their plays, negotiated a stadium deal for them, and set up the fund-raisers they’ll need to finance the season. But some part of him aches to join them on the field, like he did that day in Alvin. “Honestly,” he says, “I wish I could rewind the clock and go back and put on some pads”

Boxing was Emilio Ledezma’s first love. As a young welterweight fighter, he was known as “El Gato” for his cat-quick reflexes. Early in his professional career, at age 26, he took a shot to the eye and suffered a serious injury. Doctors told him he couldn’t risk further damage to the eye, so he decided, “I’ll put on a face mask and I can hit somebody.”

By then, he’d already tried out for the San Antono Gunslingers, a professional franchise in the short-lived USFL. When the Kansas City Chiefs conducted tryouts in San Antonio, Ledezma was one of the players who showed up (he says he was cut in the third round). He even played bass in a late-’80s hard-rock band called Pretty Ugly, only giving up the gig when he concluded that the group’s decadent lifestyle didn’t mesh with his new-found family responsibilities.

“When I played with semi-pro teams, they kept folding,” Ledezma says. “One day a guy told me, ‘Why don’t you put a team together? You know everybody.’ I thought about it and decided to call them the Aztecs.”

The team debuted in 2002, with Ledezma, in the twilight of his playing career, lining up at fullback and middle linebacker. Over the course of that season, one of the coaches quit, and Ledezma stepped in as an assistant. The following year, he took over as head coach, slowly assembling a group of players with the right mix of talent and dedication.

“The first season was hard,” he says with a smile. “I didn’t win a game. It took me awhile to develop and realize what worked and what didn’t work. Now I’m winning ballgames. I’ve lasted the longest. Semi-pro teams in San Antonio last maybe two or three years and they end up folding or calling themselves another name.”

In 2004, the Aztecs made the Texas United Football League playoffs for the first time. One of the players on that team was Chris Oquendo, now in his third season with the Aztecs. Oquendo, 21, is 6-3, 250 pounds, a big player by any standard but an absolute behemoth amongst the undersized semi-pro players that surround him. With his size, he looks like a tight end, but instead he plays quarterback, the same position he played in high school at Fox Tech. “They call me Daunte Culpepper,” Oquendo says in reference to the Minnesota Vikings’ signal caller, “because he’s a big quarterback too.”

Oquendo says he started with Pop Warner football at age 8 and found it hard to quit when his high-school career ended. “I like to win, I like to be out here,” he says. “We have a good team and I want to keep it going. I have my wife and son so I have to keep working, but I would love to make a career of football. Hopefully some scouts come out here and check me out for arena ball. Last season we got scouted for arena football, but I was hurt that day and wasn’t able to play.”

Oquendo currently works at a Utility International warehouse handling shipping and receiving, a job that occasionally gets threatened by his non-paying football work. “Last week I dislocated my fingers `in a scrimmage`, and I couldn’t really work,” he says.

Fielding a semi-pro team can be expensive. Each of the 31 teams in the TUFL are required to pay the league a franchise fee of $500 per game. They also pay for the rental of a field (this season the Aztecs will play at Mount Sacred Heart Stadium), and must pay the officials at each of their home games. In addition, the teams must pay for their players’ jerseys. To meet these costs, Ledezma charges each of his players $100 for the season. He also organizes fund-raisers, such as a recent barbecue plate sale at Auggie’s Barbed Wire Smokehouse. Players must also buy their own pads, an expense which can easily run up to $200. When combined with the demands of twice-a-week practices and weekly games, these costs would scare off many young family men, but several Aztecs cling to hope for a shot at the Arena Football League.

| Quarterback Lee Crayton works on offensive drills during a Tuesday night practice. (Photo by Mark Greenberg) |

Charles Perez, 22, paints commercial buildings for a living and plays defensive end and tight end for the Aztecs. “I played at Lanier High School and after high school I jumped straight to semi-pro,” he says. “I tried to play some college ball, but it didn’t work. It’s hard giving it up. I even coach in my spare time, for 11- and 12-year-olds. Football’s my life. I want to do it as long as I can. Who knows? Maybe I can even jump to the next level.”

Perez has a son and his wife is pregnant with their second child. He says the game is “in my blood,” but acknowledges that as his family grows, it becomes harder to find time for semi-pro ball. It’s a situation shared by Lee Crayton, 24, a San Marcos high-school graduate who plays quarterback and cornerback for the Aztecs. “It is hard, because I’ve got two little babies, and I’m a stay-at-home dad,” Crayton says. “But my family encourages me just as much as I encourage myself, so it works out.”

If any player on the Aztecs resembles the team’s coach, it’s Joaquin Hernandez. Like Ledezma, he’s a vertically challenged fireplug from the South Side with a knack for hitting. The Aztecs’ greatest strength is a brutally stingy run defense, and Hernandez is an anchor of their strong linebacking crew.

At practices, it’s obvious that Ledezma particularly enjoys the defensive side of the game, and his defensive players are so aware of their superiority that they tend to taunt the offense during drills, shouting things like, “Better watch it, O-line,” and “Coach, they’re looking scared.”

Hernandez, decked out in red high-tops, is quiet but focused. He says he returned to football after 14 years away from the game because he rode his two 12-year-old sons pretty hard during their football season, and they wanted to see if he could still play. “They believe that I can’t do it, and I’m one of those who believes you practice what you preach,” he says.

Late night practices at Palo Alto Park are family affairs for Ledezma, with his wife and their three children faithfully watching the proceedings. His 11-year-old son Jorge giddily runs around the practice field with a football tucked under his arm. “He thinks he’s the next Deion Sanders,” Ledezma says.

Ledezma’s 17-year-old daughter Bianca is his star boxing pupil. Pretty and petite, with no evidence of taking any stiff jabs or wicked uppercuts, Bianca goes by the name of “La Gatita” (an homage to Ledezma’s own history as “El Gato”). She finished second in the 2005 U.S. Championships and made her professional debut last June. Ledezma says boxing training is how he makes his living, adding that he’s coached professional fighers, Golden Gloves champions, and one fighter who made the Mexican Olympic team.

Bianca’s reliance on her dad’s ring feedback is such that when she realized she had a fight scheduled for February 25, the same day as the Aztecs’ regular season opener, she wanted to cancel it. One of the lessons he taught her was to never let the judges decide the fight for you. Knock out your opponent, so there won’t be any doubt about it. That lesson was driven home in her professional debut against DeShawnta Burton when the fight was ruled a draw, although most observers believed Ledezma won convincingly.

Ledezma’s skepticism about judges extends toward his view of football officials. At the team’s scrimmage with the Riders, he persistently questions the officials about calls he thinks they missed. One such call comes late in the fourth quarter when a pass interference penalty against the Aztecs sets up the Riders with a first-and-goal opportunity. With both sidelines screaming like it’s Super Sunday, the Aztecs shut down the Riders on four plays and run out the clock for a hard-earned 12-6 victory.

After the game, Ledezma tells his players they can win a national championship, but they must make sacrifices. Minutes later, he shows sympathy for their various commitments, but indicates that no excuses are acceptable in semi-pro football.

“They’ve got their families to worry about and all that stuff that goes along with life,” Ledezma says. “I try to tell the guys, ‘If you think you’re gonna stay home and play PlayStation and that kind of stuff, that doesn’t work.’ You’ve got to come out here and know the plays. To do something good and become a champion, you have to work for it. Nothing’s given to you.” •