A rumor on the streets of SA — streets soon to be glamourized by the high-def glow of 15 digital billboards — is that Clear Channel Outdoor, the nature-advertising arm of SA-based media behemoth Clear Channel Communications, knows it’s not going to get one more ever-lovin’ electrical signpost. So when City Council passed the “pilot program” last December that gave the Mays’ family jewel a dozen of those 15 pilot boards, Clear Channel was poised to grab prime spots.

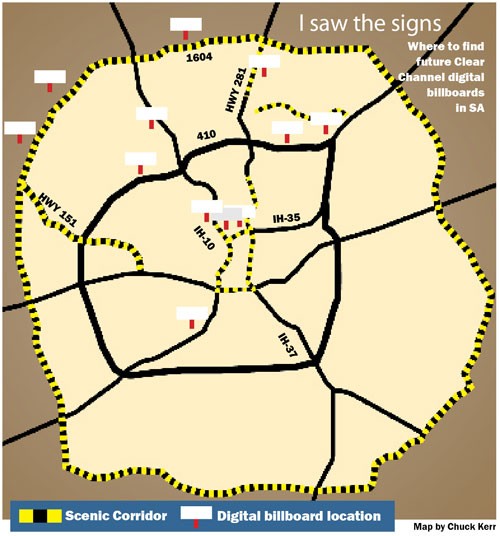

Not eight months later, the Electrical Supervisory Board, the City arm charged with reviewing the permits, approved the last of the lot, the result being seven digital billboards along 1604, 281, and inner-city I-10, otherwise known as Scenic Corridors — prettier than average stretches of highway that per an earlier City Council were intended to eventually have no billboards at all, much less blinky-shiny variable-message boards.

How on earth?

The short-short:

1. September 2007: The FHWA issues a memo announcing that “changeable electronic variable message signs” do not violate federal rules prohibiting “intermittent,” “flashing,” or “moving” lights on billboards along federally funded highways. This means states that approve them won’t jeopardize federal highway funding under the Highway Beautification Act. Preservation activists scramble to find their dictionaries.

2. San Antonio City Council approves a “pilot program” for 15 digital billboards, including signs along Scenic Corridors, as long as the latter are “minimal” modifications of existings signs, not new structures.

3. The Texas Transportation Commission adopts new rules in February ’08 that allow cities to approve digital billboards along federal roadways as long as they meet the FHWA’s mininal standards.

But here’s the sort of sad part. Although a train was clearly in motion, the City didn’t have to climb on board. Clear Channel could have rolled straight through the Pink Dome from D.C. without a stop in the Alamo City. Except they wouldn’t have had much to show for what must have been a fairly extended lobbying effort by various industry reps: So far, Houston, Dallas, and Austin have declined to go whole-hog for digital signs. In fact, Houston — the city we love to mock as the poster child for unzoned clusterfuckometry — just celebrated the removal of the first 100 billboards in an 800-billboard remediation program.

Nonetheless, City staff, in its presentation to Council for the December 6, 2007, vote, portrayed it as a do-or-die measure. Under “Alternatives” on the Request for Council Action, City staff offered only: “The sign industry contends that the current ordinance allows the installation of digital billboards. If they are correct and the City Council does not approve this ordinance digital signs may be allowed without a framework to regulate them.”

Hang on a sec. Would something have prevented San Antonio from emulating dozens of other cities around the state and country who’ve declined to authorize digital billboards along highways and other city thoroughfares? Passing, instead of the pilot program, an ordinance banning digital billboards?

“Nothing,” says Margaret Lloyd, policy director for Scenic Texas. “They have the power to do that.”

The power perhaps, but not the will in San Antonio, where the Mays family carries a big stick. The Queque last week reported on their generosity to would-be County Commissioner Kevin Wolff, who managed to stick around long enough in his second term as Councilman for District 9 to vote for the digital-billboard pilot program before resigning to run for the commissioners court. Clear Channel Outdoor officers Mark and Randall Mays and assorted company lobbyists have since donated at least $8,000 to Wolff’s campaign, although that largesse looks small in comparison to the company’s $40,000 donation last year to Foundation for the Future, the PAC that successfully lobbied for the 2007 $500-million city bond. That donation, in turn, seemed almost de rigueur, what with Clear Channel Outdoor President Blake Custer serving on one of the committees that shaped the bond program, alongside such notable local political players as Ramiro Cavazos and his former City of Phoenix colleague, City Manager Sheryl Sculley.

Those levels of entanglement might explain why an October 13 Express-News headline suggested “S.A. offered deal on digital billboards,” as if Clear Channel were doing the City a favor. The favor? When all was said and negotiated down to the pilot program, dozens of old vinyl billboards will be removed in exchange for Clear Channel’s 12 new digitals. “Right now I believe the number is over 60,” Clear Channel VP Tim Anderson told the Current. “Over 60 structures have been removed.”

The problem, charges Scenic San Antonio Chair June Kachtik, is that some of those signs were no longer being maintained, and under City rules, Clear Channel would have had to either repair or remove them, regardless of the pilot-program tradeoff.

“We have records of every tradeoff that the City was going to make,” said Kachtik. “And what we find by and large is that there was not valid advertising on many of these billboards that were being taken down.”

When they complained to the City, she said, the City’s response was, aren’t you glad those trashy signs are coming down?

“And our response was, ‘I guess we were

naïve.’”

City Development Services Director Rod Sanchez says they’re just failing to understand how the City’s sign-compliance program works. The signs are inspected pretty much annually he says, and if they’re marginal for some reason, they get a “partial pass” in the system. But “a partial pass didn’t mean that it failed,” he said. He acknowledges that at least one sign that Clear Channel proposed to demolish in the trade didn’t have a vinyl face; he couldn’t recall another that critics say was demolished in August 2007, but that Clear Channel had at first counted toward its total. None of the signs that are being removed would be required to be demolished separately under City code, he said. “They’re all good signs.”

Vance Jackson Neighborhood, Inc. President Ted Trakas says that debate misses the larger point: Evaluate the tradeoffs based on revenue, rather than square footage as the pilot ordinance does, and San Antonio’s deal pales in comparison to the deal Anaheim, California, wrangled from Clear Channel. The actual billboard numbers are close, says Trakas, but Anaheim was exchanging vinyl for vinyl, not vinyl for digital. When you compare the potential revenue difference, “Anaheim was holding out for a 10-times-better deal.”

The ratio SA brags about is roughly four-to-one, and Sanchez said that in some instances, as many as 19 passive billboards could be removed in exchange for one new digital billboard, but according to a presentation by the U.S. Green Building Council Central Balcones Chapter, Clear Channel would have to retire 49 old-fashioned billboards to make up for the carbon footprint of a single digital billboard. For the pilot program alone, this would equal 588 billboards, more than a third of San Antonio’s total of almost 1,600 signs. District 7 Councilman Justin Rodriguez, who registered the sole opposing vote to the pilot program, agreed that it looks funny coming from a council that has recently launched a green-city initiative.

“I think my feeling is there’s a commitment there to move forward on some green initiatives in our city and to be a lot more progressive,” he said, “but yet we’re allowing policies that are counter to that, such as the digital billboards.” `Read the full interview in the MashUp, page 7.`

Rodriguez lays some of the blame for the decision on the council’s relative inexperience; the vote came eight months into the first term of half of the members. That inexperience may prove costly in many ways. A little over a year from now, the feds are set to release the results of a study evaluating the impact of digital signs on drivers. In the meantime, San Antonio and other cities have been flashed a pair of studies backed by none other than the Outdoor Advertising Association of America that found, perhaps less than surprisingly, that digital billboards have little or no impact on driver safety.

San Antonio architect Jonathan Smith took it upon himself to contact Jerry Wechtel, author of a report titled, straightforwardly enough, “A Critical Comprehensive Review of two Studies Recently Released by the Outdoor Advertising Association of America.” His question: Would the City’s promise to evaluate the impact of the new signs after the pilot program expires in December do any good?

“What he told me was it’s basically impossible to measure the safety of these things for free, and the City right now hasn’t set aside any money to do the safety study,” said Smith.

Of course, the City could have waited a quick two years to see what the Feds came up with.

“One could question the judgment of those City officials,” said Scenic Texas’s Lloyd. “What’s the rush?”

Like many participants and observers in this battle, especially those who showed up repeatedly at subcommittee hearings, council, and Electrical Supervisory Board meetings to register their opposition to digital billboards, San Antonio Conservation Society President Marcie Ince thinks Clear Channel’s hometown advantage sealed the deal. And whether or not Clear Channel takes the threat seriously (VP Anderson told the Current that “we think once the public sees these digitals, they’re gonna be like what our experience has been in every other market: They’ll shrug their shoulders and go, ‘eh, no big deal.’”) Ince and her allies plan to do everything they can to make sure SA never sees its 16th digital billboard, including making it an issue in the spring council elections.

“I get the impression nobody’s really happy with these things, they’re just trying to appease Clear Channel,” said Ince. “We do not owe Clear Channel anything just because their headquarters are here.” •

Vance Jackson Neighborhood, Inc. President Ted Trakas has devoted extensive time and energy to analyzing San Antonio's digital-billboard pilot program. You can find his extensive collection of white papers at vjni.org. Here's his take on Billboard Economics.

http://vjni.org/Issues/_Digital-Billboards/20080318_Billboard-Economics_pdf.pdf

San Antonio's Council has in the past designated portions of local highways and roads as Scenic and Scenic-Urban Corridors, restricting the signage and development along these thoroughfares for "to preserve the aesthetic environment,

reduce visual blight and distraction and further promote traffic safety," as the ordinance says. Read it here.

http://www.sanantonio.gov/planning/pdf/ordinance/Scenic_Corridors_ordinance_4-17-03.pdf

Two conversations about “significant” versus “minimal”

To the best of our knowledge

Perhaps no provision of the local digital-billboard pilot program causes as much heartburn as the method for determining whether converting a vinyl billboard to a digital sign is a “significant” modification — a crucial distinction, because billboards along San Antonio’s Scenic Corridors can only be remade into digital displays if the modification isn’t “significiant.” Critics such as the San Antonio Conservation Society’s Marcie Ince ask how a company can replace pretty much everything but the pole and still call it a “minimal” modification, but wouldn’t you know it, Clear Channel (and the City to a lesser degree) has an answer at the ready. Below are excerpts from two conversations, one with Clear Channel VP Tim Anderson, another with SA Chief Sign Inspector David Simpson.

Tim Anderson, Clear Channel

I’m sure that you’re aware that one of the objections that’s been raised to some of these billboards that the Conservation Society, for instance, says that they think these are really major modifications, they’re not minor modifications. Could you tell me from Clear Channel’s perspective what the difference is between a major modification to a sign and a minor modification?

Obviously there’s probably some percentage that’s applied. For example, under TXDOT rules there’s a 60-percent threshold that says if a sign is changed or modified greater than 60 percent of the value of a new sign, then it’s considered under TXDOT rules as “major” and you have to get a new permit.

And you said “value,” so it’s based on the monetary cost of the changes?

Of a new sign. Am I making sense?

Actually, break that down if you would and walk me through it like I’m in fifth grade.

Sometimes I get into lawyer mode and I speak a little too lawerly and I apologize. What TXDOT says is they don’t consider any modification major unless whatever you’re spending is 60 percent or more of what a new sign would cost. So, if a new sign today would cost $100,000, I’m not allowed to go and make any modification that exceeds $60,000. That to them is a new sign.

And you’re saying 60, six zero?

Six zero, yes, ma’am. Sixty. and if you’ll notice in the ordinance itself there is no percentage, so we have worked with the City to ensure that we keep any mofications we make significantly below a 60-percent threshold. So, again, what is significant? That is the question that some of the opponents are trying to use to stop our changes, but the amount of changes we’ve made have been significantly below a 60-percent threshold.

Let’s say you’re building a brand-new billboard, not even a digital one, what’s the major expense in putting up a new billboard?

My gosh ...

I mean, if you were gonna break it down, what costs the most? The pole? The sign itself?

You know, in all honesty, and I’m not ducking your question, Elaine, it’s so dependent on so many factors. It’s how much does the lease cost, the site preparation for the pole, how much does steel cost that day, literally that day. You know, what type of sign are you building is a part of it -- it’s really hard to say, oh, gee, what is the most expensive part of the sign. It’s kind of hard, I don’t want to be accused of misleading anybody.

Sure, I understand. So in the TXDOT formula, when it says the cost, you can’t spend more than 60 percent of the cost to put up a new sign if you’re just modifying it, does that cost include all those things: leasing, the whole shebang, not just the physical sign itself?

It would be the cost not of, you’re not allowed to include lease costs; in other words I can’t include what I’m paying the landowner for the use of his land, but all those other costs would be included.

OK, got it, so labor, the cost of steel, manufacture, the whole thing?

Yeah.

I've seen prices both $250,000, even up to $500,000 for the cost of a new digital billboard. Is that anywhere in the ballpark and how does that compare to the cost of the construction of just a new old vinyl billboard?

Uh, the faces are anywhere from $300,000-$500,000. So yes, you're in the ballpark. And that again is the face. It's something where essentially what we do is, we take the old face, that was holding the vinyl, we remove that and take what is essentially a cabinet and bolt the cabinet to the existing structure. So that's how that works. It's not a brand-new sign in that context, it's just a face change.

So, really, it's like bringing the wire up and putting on this cabinet that has the ...

Yeah.

David Simpson, Development Services, City of San Antonio

`Explaining how they calculate the percentage cost of a digital-billboard modification`: Can we get estimates in terms of the value if it were to be built today. And then can we also get an estimate of the work that you were requesting to be done to the structure to provide the digital face. And then we compared those estimates and looked at the percentages and they all fell well, well within that 60 percent, and typically we’re seeing them near about 30, 20, 30, 40, so they were all well less than half the cost, and so, it was so subjective we had to find something for lack of a better term to hang our hat on. And so there again we referenced the Texas Governmental Code ...

And that was based on TXDOT’s ...

Actually, I don’t think it’s TXDOT per se, I get so narrowminded in my Chapter 28, let me see if I can’t find where I found that ... Local Government Code, I’m sorry. It’s the Texas Statutes and Local Government Code.

So are those price comparisons, are those part of the public record?

Yes, ma’am.

Because a lot of the opposition is looking at it structurally and saying, how can it possibly be minor when you’re taking more or less the entire top and changing it out.

And that’s the whole idea. One person’s idea of significant is, depending on what the objective is, would be different, particularly in this instance. So the director took the position, OK, where do we have a reference point to what is significant? And being that the Texas statutes on local governmental code had outlined that you can perform work, that you can even relocate these structures, um when it’s governmental action or when there’s changes required, or when it’s an act of God, so to speak, some of these events, would drive the fact that they have to do something to these structures, we would allow it if it falls within that percentage of the actual cost of that structure.

Now here’s my other question: There was a lot of discussion about non-conforming signs, when this was coming through the system. What is a non-conforming billboard?

Well, quite honestly, I guess again that’s somewhat of an interpretive issue that there again may be better suited for the director, but depending on who you ask and what their objective is, you have different opinions. You could view the term non-conforming as any structure that exists that wouldn’t be allowed today, correct? So, therefore, in essence, one could say that all structures are non-conforming. But for the purposes of billboards, it’s a more of a height-size-setback-spacing issue. So I think it has to do with those parameters in regards to non-conforming structures, or signage.

Initially I know that opponents of digital billboards had wanted non-conforming signs not to be allowed to be converted to digital. But I don’t think that actually came through as part of the pilot program, or am I missing that in there?

Well, uh, well, again, I guess the language as such is that it provides for new structures and existing structures and corridor signs -- there’s the three categories. And of course if it’s an existing sign, it requires minimal, well it’s minimal to meet the minimal and safety standards ... OK, it’s an existing structure that requires some work. At what point does that work become “significant”? So, we’re requiring the work because we want it to meet the building-code requirements, but we wouldn’t have allowed it if it had exceeded the percentage laid out by the Local Governmental Code because at that point that was kind of our directional for “significant,” if you will. so I guess in that sense this is viewed as re-faces, and we didn’t have any new structures built, so they were all existing structures, so we referenced everything under that category.

So even if it was, say, non-conforming and you were talking about the setback, it could be converted to digital provided it was still minor, but it could also at the same time be addressing the non-conforming issue.

Correct.