| "THEY DON'T REALLY EAT ANYTHING `IN THEIR FIRST YEAR OF LIFE`; WHERE DOES THAT MONEY GO?" – NPR, AUG. 8, 2006 |

For the average middle-class family, the U.S. Department of Agriculture says it will cost $184,000 to raise a child from birth to the age of 17. Last week on NPR, commentator Michelle Singletary admitted the figures are all over the place, from rural to urban centers, but in the first year of your baby's life, you can expect to pay, on average, $7,300. (Where does that money go? Don't they have a free-food fountain at their immediate or sterilized-bottled disposal?) "The largest baby expense is daycare," Singletary answered. Since parental leave is only slightly longer than the summer romance in Grease - a whopping 12 weeks of unpaid leave vouchsafed by the U.S. Department of Labor - you most likely will put your newborn in a facility. For the privilege, Singletary says, Americans can expect to pay $280 a week (roughly the same amount as 15 undergraduate hours at the University of the Incarnate Word. Too bad daycare tuition is not the kind of big-ticket item you can get at a baby shower). Then there's the matter of a dearth of quality centers. U.S. Vital Statistics says Bexar County has seen a slight increase in its annual stork deliveries, with 25,600 babies born in 2005. Match that up with the number of child-care providers: Around 1,000 licensed and registered places, from commercial centers to those operated out of private homes, offer child supervision countywide. It's the same shortage all over the country. And parenting handbooks will tell you that if you've left your search until the last minute - say, the end of your second trimester of pregnancy, when you have enough of a bulge that people are bringing their hands toward your belly like vaqueros warming by the fire - then you will have to break the law and leave your child unattended, preferably with the TV on and an ample supply of cold cereal. (That's what Jacob Calero and Michelle De La Vega of San Ramon, California, did this year when they left their two children, one an autistic 5-yearold, home alone while the couple took a New Year's Eve trip to Las Vegas. The Associated Press noted that the couple was able to find a dog sitter for their puppies.) The market of child-care tip-givers is such a silt-clogged waterway that even the Dummies reference-book series has devoted a volume to the subject. And they all seem to suggest that choosing a provider is a process you should approach with Hemingway's "animal instinct of impending doom" (to borrow George Packer's phrase). Author Ann Douglas suggests in The Biggest Mistakes Parents Make When Choosing Childcare that as soon as the EPT reads positive, you should make two calls: one to your mother, then another to a daycare provider, to put the unnamed, sexless, fertilized egg on a waiting list. Otherwise, they won't get into any place worth a damn. Douglas said that.

| “WE JUST DO WHAT THE LEGISLATURE SAYS WE DO, BUT YOU DON’T WANT TO BE JUST THE LITTLE GESTAPO OF CHILDCARE LICENSING.” – CATHRYN NEWHOUSE, CHILDCARE LICENSING, TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY AND PROTECTIVE SERVICES |

Children under careless or dubious supervision are not just the stuff of Grimm's fairy tales and guidebook pitches. Just last month, authorities in Cookeville, Tennessee, raided Little Learners Daycare and found little dreamers on the floor, napping, while fumes from the licensed operators' meth-brew - ephedrine, propane tanks, iodine, drain cleaner, and meth oil - wafted into their hairless nostrils. That's precisely why operators are monitored by Child Care Licensing, a division of the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. Registered childcare providers can expect unannounced visits at least once a year from people like Cathryn Newhouse, a cinnamon-haired Canadian three years from retirement, who wears a smiley-face button on her nametag reading, "Attitude is everything." CCL looks into personnel files, staff-member-to-childratios, field-trip procedures (during the summer, there's a big push to make sure people don't leave kids in cars), and other health and safety minutiae that might be overlooked - making sure, for instance, that no one has left anything a child could suffocate on, like that friendly-looking, unused, cottony diaper. Newhouse's office also investigates complaints. "Sometimes people complain about whether a kid's hair is combed when they come pick them up." (Yeah, parents can be picky.) But she also tries to give kudos: When a dingy center repainted, she put that in its report. Newhouse met with the Current at Good Samaritan's Westside facility for a

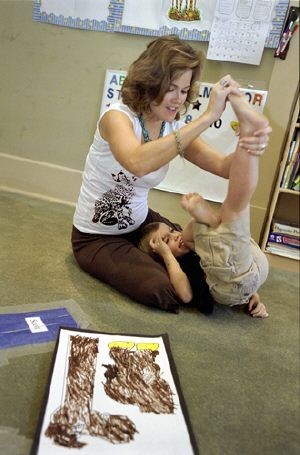

| Tess Coody (center) looks in on her son Kieran, 4, during snack time in the firm's onsite childcare facility. |

| "THE CHRYSALIS IS READY TO BURST. WE JUST HAPPEN TO BE AHEAD OF THE CURVE." – TESS COODY, GDC |

Tess Coody, 35, looks like Keri Russell, the star of that old show Felicity. She hears this all the time. When her hair was longer, people would ask if she was the marketing firm's intern. When the COO and partner was pregnant with Brendan in 1999, she led the charge to get care providers on-site (including the personal caregiver she uses at home). Employees donate equipment (there are still rotating milk-buying days) and the company invested $10,000 that first year. Call it a co-op, but don't call it a new concept. The nation's first co-op nursery school was started in 1916, by 12 faculty wives at the University of Chicago, who pooled their resources and volunteered to oversee a childcare program while the women moonlighted with war work. During World War II, Roosevelt's Federal Works Administration created a childcare program, featuring nurseries that were poorly supervised and inconveniently located for mothers who once again went to work in war industries. As Alice Kessler-Harris writes in her book Out to Work, "So inadequate were `the nurseries` that rumors circulated about executives in war industries who wanted to set up their own child-care centers." Since then, women have secured a more permanent place in the workforce (Hey, Betty Friedan, ladies now make up more than half the labor force!). Which brings us to the most obvious point about childcare: It exists because women work. The U.S. Census Bureau said of the 14.6 million women with children under the age of 6 in 2004, more than 55 percent were working. "I'm not bashing daycares," says GDC's Coody of a mother's modern-day conundrum. "Some of our parents still choose to use them ... But how is it better to go somewhere 20 minutes away? As parents, where does our right to direct and manage the care of our children begin, and the state management of it begin? We've worked for lots of clients who really believe in compassionate-conservative, family values. If we're going to say in the state of Texas family is the bedrock of society ... `then` live that." So far, "living that" has meant giving GDC's childcare the marketing treatment - media outreach to all the local news outlets, creating a website (Familyfriendlyworkspaces.com), getting endorsements from Councilman Kevin Wolff and state representatives Joe Straus and Mike Villarreal, and volunteering hours of work - valued at $350,000 so far - to get the state legislature to consider a "take your child to work" category for childcare next year. Living that also means business-as-usual, such as holding a graduation ceremony this month for the 4- year-olds who will soon be starting preschool (Miss Karen, who's worked at the GDC care center for a year, said, "The separation anxiety is usually on the side of the parents. The kids are more stable"). GDC also has to get the fire marshal to approve their third-floor nursery, add an emergency exit to the playground, and get the OK from the Metropolitan Health District before CCL's August 23 deadline. If they don't, would law enforcement bust up GDC's party room and lead the kids away, as the tykes hold hands like a paper cutout? "If they're not in complete compliance with what we need by August 23, they would not be allowed to have children in their center. We could potentially seek a legal injunction for them to stop," Child Protective Services' Mary Walker explained, giving a worst-case-scenario. "But it's all been quite amicable. They are professional, law-abiding folks, and this is mandated. I don't think there would be any need to send sheriffs out there." Indeed - we all know the best parties are the ones where the cops don't show up. Post-script: After the Current's production deadline, the state gave Guerra, Deberry, Coody a temporary permit to operate its daycare.