|

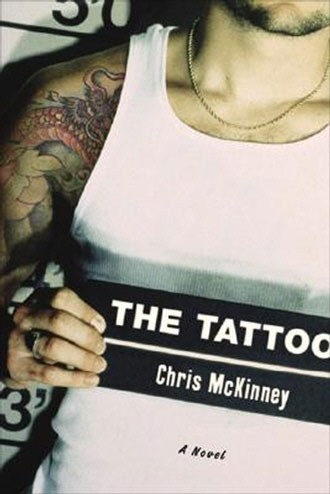

The Tattoo By Chris McKinney Soho Press $12, 248 pages |

Lately, I’ve taken to retyping, printing, and scotch-taping these passages to the wall behind my desk. The most recent to join Philip Roth, Haruki Murakami, Gary Lutz, and Janet Malcolm, comes from Chris McKinney’s 1999 debut novel The Tattoo:

“Suddenly the words, ‘fuck it,’ flashed into my mind in big, bright neon, Vegas-style letters. Those two wonderful words that many of us cling to. It’s like your mind, it can conjure up all sorts of rationalizations, arguments, and the debate can go on and on, but when you say, ‘fuck it,’ it’s like the ace in the hole because there’s no real argument that can stand against it. ‘Fuck it’ can mean you made a decision or you let life make the decision for you while you were totally uninterested in it anyway. ‘Fuck it’ is absolute, it covers all bases.”

These are the words of the novel’s central character, Kenji Hideyoshi, a Hawai’ian of Japanese descent growing up on the poverty-stricken, “windward” side of Oa’hu — the rural region that isn’t covered in Fodor’s Hawaii.

There’s another quote worth pulling, not for its wall-value, but for the author’s prescience:

“Cal knew that Ken took pride in his story, and that it probably irritated him that no one would read over it or make a movie out of it. Sure, if you take all the pidgin out, exchange Ken with some white guy from West Virginia, then there’d be an audience. But Ken was Japanese and brought up in ‘paradise.’ Paradise was never the compelling setting unless it was falling or lost.”

Whether intentionally or not, with these words McKinney foresaw his future as a Hawai’ian writer. The book, published when McKinney was 26, would win the Hawai’i Book Publishers Association’s highest honor, the Ka Palala Po’okela Award. It would also earn McKinney the Elliot Cades Award, the state’s highest literary honor. Nevertheless, his novel would not leave the islands until this year, with its reissue by a New York publisher.

The Tattoo is a frame tale in three acts that stretches out from the cells of the Halawa Correctional Facility, where Hideyoshi, convicted on a manslaughter charge, is having the Japanese kanji symbol for The Book of the Void by 17th-Century samurai-author Miyamoto Musashi tattooed on his back. The tattooist is white and mute, and therefore the consummate confessor, as well as the stand-in for the until recently non-existent mainland American reader.

In Hideyoshi, McKinney has crafted a character tormented by his self-awareness and a life story that the reader will often forget is fictional. Hideyoshi’s tale begins with his struggles to fit in as a Japanese among native Hawai’ians, and the development of his fatalistic identity under the influence of an abusive father. Hate swells inside him, and only by feeding off the rage is he able to escape the windward side for the city. But this rage also consumes him, and once in Honolulu he finds himself swallowed by the criminal underworld. When love offers redemption, he is forced to return to the windward side, where, in the end, he commits the homicide that lands him in prison.

Throughout the book, Hideyoshi as narrator references Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man and Richard Wright’s Native Son. This leads one to believe that McKinney intended his book to serve the same mission: to give voice and humanity to Hawai’i’s oppressed classes. And on one level, book succeeds as an ethnography of Hawai’i’s complex culture, comprised of indigenous people and the children of Asian refugees, marginalized by white tourists and military personnel; of youth trapped by mountains and oceans and poverty. The strength of McKinney’s prose is primarily in his use of the dialect spoken by the windward Hawai’ans, and the bitter reality reflected in the poetry of their pidgin.

If McKinney’s ultimate achievement is his portrayal of Hawai’ian culture in a way that the mainland Americas — those who’ve never seen, nor ever will, anything but the tourist side of Hawai’i — can identify with, then the ultimate failure belongs to the mainland American publishing houses for ignoring the book for so long.