Even if you only studied art by default in school, you might’ve made a quick-and-dirty monoprint by smearing paint on a woodblock and transferring your masterpiece onto paper. And many of us are versed in at least the basics of screen-printing (aka silk-screening or serigraphy) thanks to its relative simplicity and everyday applications (band merch, beer koozies et al.). But when you dive into etching, lithography, collotype, photogravure and other related processes, you’ll find that printmaking can be a laborious and complex practice involving precise chemistry, light-sensitive materials, multiple steps and specialized tools such as etching needles, zinc plates, gelatin sheets, leather rollers and stone grinders. Not exactly something one picks up as a casual hobby.

The most prevalent form due to its commercial use for posters, magazines and advertisements, offset lithography exemplifies printmaking’s most obvious purpose: to print multiples of the same image. But for certain artists working in the versatile realm of printmaking, the ability to make dozens, hundreds or thousands of the same image might be less important to their output than the nuances and visual idiosyncrasies of the medium itself.

California transplant and longtime San Antonio resident Kent Rush fits snugly into this category of artists. While he does print numbered editions of the same image, his masterful work explores the unusual tones, textures and patterns intrinsic to printmaking.

Born in the Bay Area, Rush inherited a knack for making things from his father, an industrial art teacher who died when Rush was a child. Although he excelled at art during high school, Rush opted for an architecture program before settling on art, with teaching being the end goal. After earning degrees from the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) and the University of New Mexico, Rush relocated to Texas to help launch the printmaking program at the San Antonio Art Institute, a bygone school housed on the grounds of the McNay Art Museum. Short of a return to California from 1979 to 1982, Rush has remained a constant presence in San Antonio ever since, exhibiting nearly everywhere imaginable and teaching generations of future artists at UTSA for 36 years (1982-2018).

In addition to being one of the original founders of Blue Star Art Space (now Blue Star Contemporary), Rush boasts a long relationship with the McNay. Beginning with a solo exhibition in 1977, his history with the museum includes a retrospective in 1998 and the recently opened showcase “100 Years of Printmaking in San Antonio: Kent Rush.” Organized by prints and drawings curator Lyle Williams in conjunction with a Tricentennial series exploring the history of printmaking in the Alamo City, the exhibition expresses a lot in a relatively compact setup. But save for an informative video that shows the artist at work in his studio, viewers shouldn’t expect much immediate gratification. Regardless of the mediums at play (Rush works between drawing, painting, collotype and lithography with an emphasis on “the space between photography and printmaking”), his work requires viewers to slow down and contemplate what they’re looking at and, perhaps more importantly, how and why it was made.

The word “subtle” has been used with regularity in descriptions of Rush’s work. And while that feels like an accurate descriptor for his figurative output — including photo-realistic drawings, photographs and prints celebrating mundane objects, concrete embankments and freeway underpasses — his collage-like abstractions — which often fuse representational fragments with intense studies in mark-making — are far from subtle. Taken as a whole, his often inter-related bodies of work run the gamut from minimalist to maximalist, from quiet, controlled arrangements to chaotic storms of intersecting lines.

With multiple mediums and styles at play, one might question the connective thread or visual continuity in Rush’s work. Arguably the most obvious “theme” that emerges is the artist’s affinity for found objects and ignored corners of the urban sprawl. Water run-off stains in drainage ditches are presented as expressionistic collaborations between man and nature; concrete is celebrated as an overlooked source of imperfect beauty; gum wrappers become artifacts — dust under the rug of of modern civilization.

“For about 20 years, I was photographing primarily concrete objects, Rush told the Current during a recent tour of his McNay exhibition. “What I really love formally are just basic shapes … So I would scour the countryside trying to find odd concrete objects because, for one, concrete’s kind of like the base of our whole existence in the modern world. It’s like our foundation material but nobody pays any attention to it.”

In terms of materials, however, paper might be the biggest common denominator in his work. Regardless of what processes and tools are involved, the vast majority of what Rush makes could be categorized as “works on paper.” Even his large-scale paintings, monochromatic abstractions reminiscent of Japanese screens, are rendered on paper that’s been stretched like canvas.

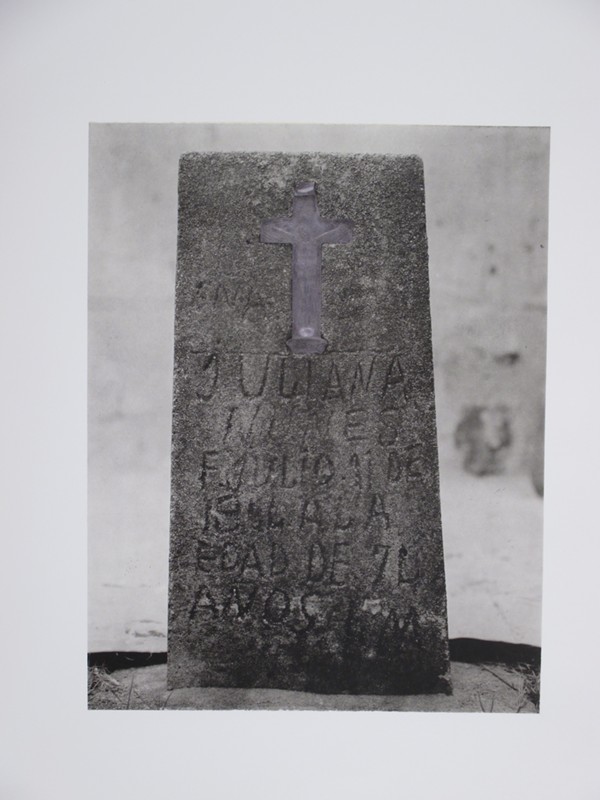

Interestingly, some of the more immediately relatable images in the new exhibition are from his most recent body of work. Titled Recuerdos, the still-in-progress series of collotypes involves Rush visiting cemeteries across South Texas to photograph humble concrete gravestones with a large-format camera, a well-worn backdrop and a light-diffusing apparatus. While it could be seen as merely the latest chapter of Rush’s artistic love affair with concrete, it feels like a significant departure since it introduces a more obvious human connection. Describing one of the images in the series, which depicts a hand-lettered gravestone inlaid with a purple glass cross, Rush explained, “There’s kind of sentimentality that doesn’t exist in the more professional tombstones.”

Standing out as something of a wildcard, our personal favorite in the show conjures an odd dichotomy — a weathered statue of Saint Francis positioned in front of a panel salvaged from a vintage pinball machine. “My wife (local artist Victoria Suescum) and I both love what we call vernacular art,” Rush said. “And even though this isn’t vernacular art, because it’s cast concrete, it kind of fits in because it’s the kind of stuff people put in their yard, and every year they paint them and pretty soon they get encrusted … and you can’t see the details ... This series has that same notion, there’s kind of a sentimentality there, a preciousness.”

100 Years of Printmaking in San Antonio: Kent Rush

$15-$20, 10am-4pm Tue-Wed, 10am-9pm Thu, 10am-4pm Fri, 10am-5pm Sat, noon-5pm Sun, Through September 30, McNay Art Museum, 6000 N. New Braunfels Ave., (210) 824-5368, mcnayart.org