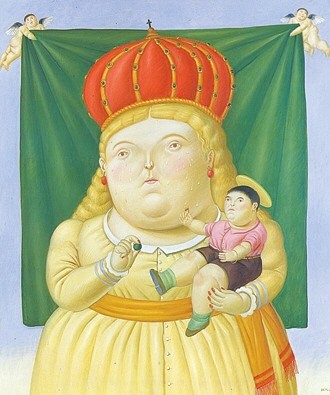

| “Our Lady of Colombia” (1992), part of the Fernando Botero retrospective that opens May 26 at the Southwest School of Art & Craft and the San Antonio Museum of Art. |

| Botero: Beloved artist of the Americas May 26-August 19 San Antonio Museum of Art Southwest School of Art & Craft San Antonio Public Library Downtown For a complete schedule of events, including lectures and classes, see Boterosa.org and the Current’s weekly calendar of events |

The artwork is appearing at the San Antonio Museum of Art, the San Antonio Public Library, and two venues at the Southwest School of Art & Craft, and represents the first major U.S. retrospective for the Colombia-born artist since 1974.

San Antonio has the opportunity to feast its eyes on works spanning almost the full breadth of the 75-year-old artist’s career. But not quite.

Except for a few pages in the show catalog and for a lecture set for June 19 at SAMA, the exhibition ignores some of the most powerful paintings and drawings in Botero’s portfolio: 80 works collectively known as Abu Ghraib.

Most of these works were completed in 2005, long before the final details of this exhibition were set in stone. Failing to include at least some of these paintings or drawings in this show is like mounting a retrospective of Picasso’s career and ignoring “Guernica,” or showing Goya’s works and leaving out his “Disasters of War.”

To their credit, show organizers include samples of Botero’s dark side — what Botero has referred to as “a parenthesis,” where he subjects his stylized and distorted human forms to abuse, cruelty, and death.

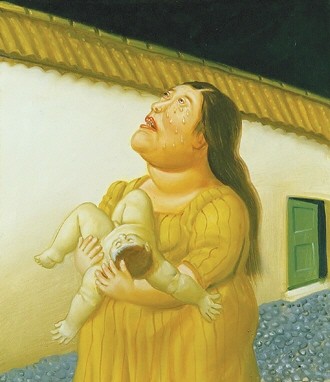

| “Sorrow” (2004) |

But it’s one thing to offer depictions of innocents caught in the crossfire of a vicious Colombian drug battle, and another thing entirely to hit the still-raw nerve of Iraqi detainees tortured and humiliated by the U.S. military, with graphic displays of urine, vomit, snarling dogs, bleeding rectums, and bloody batons.

Go to YouTube and search for “A Permanent Accusation,” and you’ll get one interpretation of the struggles Botero faced finding a U.S. museum to display these pieces, along with a glimpse of many of the pieces that can’t be seen at this show.

Since that video was produced, Botero’s Abu Ghraib series has been shown in a private gallery in New York City last fall. The paintings and drawings also attracted some 15,000 visitors over a seven-week span earlier this year to a library on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley — an event staged by a graduate student and about 30 volunteers.

According to an International Herald Tribune article covering the UC Berkeley show, “when Art Services International organized a Botero retrospective currently on tour, it offered the Abu Ghraib series to American museums and found no takers.”

“American museums didn’t want this exhibition,” Botero was quoted as saying. “For what reason, artistic or political, I don’t know.”

Dr. Marion Oettinger, Jr., director and curator of Latin American Art at the San Antonio Museum of Art, said in mid-May there was no chance of getting the controversial artwork into the show so close to the opening. He added that the contract SAMA had with Art Services International was finalized two years ago.

Although Botero clearly would have preferred that the Abu Ghraib artwork be included, he will be supporting the event in person at SAMA’s member preview Thursday May 24.

That’s good news for honorary co-chairs Mayor Phil and Linda Hardberger and others in the San Antonio community who are supporting the exhibition. Oettinger says the city-wide celebration is modeled on the crowd-pleasing success of SAMA’s 2003 Dale Chihuli exhibition, which concluded with the installation of his intricate and colorful Fiesta Tower glass sculpture at the San Antonio Public Library’s central location.

By making an appearance at this show, Botero is evidently not prepared to make the ideal the enemy of the good. In that same spirit, we can recommend that San Antonians make the most of this sweeping exhibition, starting with the paintings, drawings, and sculptures on display at SAMA.

A hefty catalog accompanies the exhibition, with articles by Dr. John Sillevis, curator of the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (who is the guest curator for this event), Dr. David Elliott, Director of the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, and Dr. Edward Sullivan, Dean of the Humanities and Professor of Fine Art, New York University. The show catalog details the Baroque influences on Botero as he grew up in Medellín, studied in Bogotá, and traveled to Barcelona, Madrid, and Florence, where he fell under the sway of Velázquez, Goya, and the masters of the Italian Renaissance.

Tim Foerester, director of exhibits, says the first thing visitors will see at SAMA is “Hand,” a monumental bronze outside the museum’s entrance. Together with “Smoking Woman” and “Rape of Europa,” it’s one of several monumental sculptures at the museum.

Oettinger says most of the paintings will be in SAMA’s 7,000-square-foot Cowden gallery, and most of the drawings, which reveal Botero’s fluid mastery of line, are housed at the Southwest School of Art & Craft venues.

The artwork in the Cowden gallery will be organized thematically, Foerester says, in a semi-chronological way. Judging from an advance copy of the catalog, the first few paintings will immediately challenge anyone who thought that they had Fernando Botero all figured out. One of Botero’s earliest compositions, “The Boy from Vallecas” (1959), was inspired by another painting with the same name by Velázquez (circa 1635-1645), who made a portrait of a court dwarf. Botero’s boy is not just capacious, filling the entire frame, he’s also dead, and dressed for a funeral, with a jarring brushstroke and facial colors with shading that contrasts sharply with the dichotomous background.

The next grouping of paintings traces the influences of Botero’s exposure to Baroque Spanish colonial through the Catholic church — as the show’s organizers put it, “the sumptuous decorations that flourish on the walls … with gaudy angels, tormented saints, the physical agony of Christ, and the pearly tears of the immaculate Virgin.”

In works like “Christ” (1999) and “Our Lady of Colombia” (1992), visitors can see hints of religious sculpture and painting. But in “Our Lady of Colombia,” Botero’s simplified background and comic distortions give the painting a surreal, cartoon-like whimsy, closer in spirit to Magritte or even Bruce Kliban than Caravaggio or Peter Paul Rubens.

While thoroughly contemporary, Botero was clearly inspired by the classics, some of which were pretty odd in their own right. His reverse-profile diptych called “After Piero della Francesca” (1998) is a weird pair of paintings, as monumental as Easter Island Moai sculptures. But the source of his inspiration, Piero della Francesca’s portraits of Federigo, Duke of Montefeltro, and Battista Sforza, Duchess of Urbino, are almost as strange.

Although many of his visual distortions create an almost-comic effect, like those Photoshop techniques that enlarge the eyes or ears in magazine ads, Botero doesn’t always distort his forms for the purpose of parody or satire. “I do the same with my oranges and my bananas, and I have nothing against these fruits,” he notes.

The painting “Still Life with Mandolin” (1998) reverberates back to the pivotal moment in 1956 when Botero stumbled upon the proportion-warping effects that would become his life’s work. He was in Mexico City then, drawing a mandolin, and decided to dramatically shrink the size of its hole. It was “like going through a door and entering another room,” Botero said, according to the catalog notes. Like many of Botero’s still lifes, Botero plays tricks with the eye, giving the weighty stem of the instrument the appearance of falling forward into the viewer’s arms, following the flow of the blank sheet music as it cascades off the edge of the table. A shuttered window is open just a crack, and in many other still lifes, Botero makes use of a framed mirror or open drawer to tease the eye.

Some of Botero’s still lifes are unsettling, with an eerie sense of foreboding. His almost-proportionate “Pineapples” (1970) are half-eaten, abandoned, and starting to attract flies and ants. His wildly voluminous “Pear” (1976) has a tiny bite taken from one side, and small worm poking out from the other.

Despite his vivid use of colors, however, a sense of sadness and melancholy permeates many of Botero’s oils and pastels. “The Widow” (1997) is based on Botero’s childhood memories of family life after his father died. “The Orchestra” (2001) features four players under colorful lights who each look as if their best friend just died. “Melancholy” (1989) captures the loneliness of the closeted cross-dresser, who only has a hand mirror for company. Even “Dancers” (2002), one of Botero’s most festive pastels, features a cast of characters who seem barely able to crack a smile.

The sense of sadness and eerie foreboding in so many of Botero’s pieces escalates to graphic carnage in works like “Woman Falling from a Balcony” (1994), “The Wall (Execution)” (2004), “Sorrow” (2004), and especially “20.15 Hours (Massacre)” (2004), in which an upended room is littered with dismembered body parts.

Botero, who stays away from his homeland as a precaution against kidnapping, is no stranger to violence. In 1995, a bomb hidden in one of his bird-shaped sculptures killed 23 people and injured 200 in Medellín, his hometown. He requested that the wreckage of that sculpture be left untouched, as a monument to violent stupidity, and he donated a second sculpture, called “Bird of Peace,” which now stands a few feet away.

In the same way, Botero refuses to sell or profit in any way from his Abu Ghraib series of paintings and drawings. But he has made it clear that if he can’t profit from his most memorable images, maybe others can. “Art has to be seen,” Botero says in the International Herald Tribune article. “This is a testimony. It’s not anti-American, it’s anti-inhumanity.”