Sex proliferates on TV and movie screens, but the gay rights movement is increasingly abstaining, leaving queer youth without a guide

| Be afraid, be very afraid: Safe-sex education has shifted from promoting healthy sexuality to a new tone that harkens back to the scare tactics of the early-to-mid '80s. |

Over the past two decades, queer communities have paid more attention to the needs of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender youth. We, and they, have fought for high-school gay-straight alliances and created state-funded projects like the Massachusetts Safe Schools Program and California's Safe Schools Coalition. More books, both fiction and nonfiction, are aimed at a gay-youth market, and teen-oriented TV shows, such as The Real World and American Candidate, feature gay participants.

In a profound way, however, the GLBT movement is seriously failing queer young people in matters of sex. Sure, Ellen and Rosie have come out, and we can all laugh at Evangelical Christians targeting SpongeBob SquarePants, but where can young gay men and lesbians learn about queer sex? Probably not from their parents or from their school's sex-ed programs. Not from safe-sex and HIV-prevention programs that, in recent years, call attention to the dangers of sexual activity. Not from shows like The L Word and Queer As Folk, or endless website advertisements for circuit parties, or porn sites that depict silly, overblown sexual fantasies and that have nothing to do with the realities of everyday human sexual interaction. The trouble here isn't with learning how to put tab A into slot A, or what lube to use, or what two women "do together" - most people can figure that out pretty easily. Nor is it with learning what one likes sexually, which can be figured out through trial and error. Rather, it concerns how to think about yourself as a sexual person, what sex means to you, and how it is intrinsic to your identity, your life, and your relationships. How do young queer kids learn how to be gay? How do they learn how to be sexual? How do they learn to think of themselves as sexual human beings with queer sexual desires?

Young queer people today are growing up in a world that, in both gay and mainstream culture, gives them deeply mixed signals about sexuality and sexual behavior. At best this is confusing; at worst it is harmful. The two historical circumstances that made growing up gay so unique for those born in the mid '80s and after - the fight for marriage equality and the AIDS epidemic - are also making it almost impossible to have informed, healthy, and sane discussions about sexual desire and sexual activity. That's because in recent years the clanging of wedding bells and the insistent tattoo of bad news about HIV transmission (much of it fueled by anti-gay hysteria in the mainstream media) has completely shaped - distorted, really - how the gay and lesbian community talks about sex. Over the past five years, safe-sex education has largely shifted from promoting healthy sexuality and sexual behavior to a new tone that harkens back to the "be afraid to have sex" scare tactics of the early-to-mid '80s. Moreover, the fight for marriage equality, and the elevation of marriage as the idealized queer relationship, has moved front and center in gay politics and, to a large degree, in the imaginations of young gay people, much to their detriment.

While the conservative and religious right (and even many moderates and liberals) accuse the gay movement of injecting sex into everything, the reality is radically different - in fact, the movement has been quite consciously removing sex from everything. Television shows like Will and Grace and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy that win awards from GLAAD present us with images of asexual gay men. Transgender politics generally avoids all issues of sexuality, concentrating instead on gender identity and expression. And, all too frequently, misinformed, hysterical AIDS reporting is taking the sex out of safe-sex. Now, in a stunning display of political engineering, the gay-rights movement has actually taken the sex out of marriage.

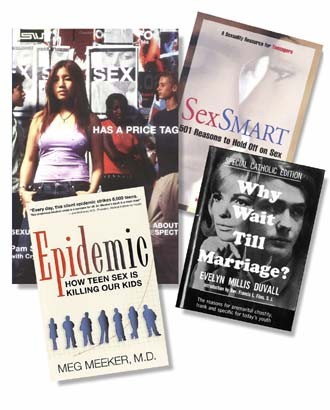

There is a great, doleful irony here. In almost all the community discussion of marriage equality, the word "sex," or even the idea of "sex" - is glaringly, appallingly absent. This isn't to suggest that we're going "back to the 1950s"; the 1950s had a healthier attitude about sex and marriage. The standard teen sex guides of the 1950s and '60s - Evelyn Millis Duvall's 1950 Facts and Love and Life for Teenagers and her 1965 Why Wait Till Marriage? (which offers "the reasons for premarital chastity, frank and specific for today's youth," according to the cover) were huge bestsellers - are quite clear that sexual pleasure is one of the great joys of marriage and that the intimate emotional, physical, and psychological relationships fostered by marriage are unique and wonderful. But you'd never know that from the rhetoric of the marriage-equality movement. It has become so focused on securing the right to civil marriage that it promotes a sexless image of gay marriage and gay life. It's a shrewd if hypocritical political tactic, and one that sends a dangerous, duplicitous message to gay youth.

| Marriage, many of its proponents argued, would help end the AIDS epidemic because it would give gay men the option - even the mandate - to pair up and be monogamous. |

Teaching courses on gay and lesbian issues at Dartmouth College over the past five years, I suddenly realized that last year's freshman class was born in 1986. This means that they grew up in the shadow of the full-blown AIDS epidemic in the United States, which was continually connected with gay-male sexual behavior. It also means they grew up in a media culture increasingly comfortable with depicting homosexuality. They grew up watching tapes of Tootsie and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, and they were 12 when Will and Grace premiered on television, in 1998. Hell, forget Will and Grace; at the same age, thanks to Bill and Monica, they even learned the details of oral sex on the evening news. Why Wait Till Marriage? Indeed.

They also grew up with the idea that same-sex marriage was an actual possibility during their lifetimes. In 1986, the Lesbian and Gay Rights Project of the ACLU suggested that the time had come to launch the fight for marriage equality. By 1993, the battle for same-sex-marriage rights in Hawaii was headline news. Since that time, the issue has grown larger than its proponents or critics could have imagined. It is now, like it or not, the most salient political and cultural gay-rights issue.

Before the current shift in HIV-prevention education and before the advent of same-sex marriage, it was a hallmark of queer life that sex had positive value and that gay relationships, which, by necessity, existed outside of legal matrimony, were as valuable, moral, and honorable as any connubial union. The discussion has now changed from encouraging people to engage in and enjoy sex, to how to control sexual activity. HIV-prevention discussions that should be about safe sex now focus on having less sex. Discussions that were once about how to explore one's sexuality through various types of relationships are now about how (presumably monogamous) marriage should be the goal of all lesbians and gay men. Goodbye, sexual liberation; hello, strict sexual regulation.

The connection between AIDS and marriage here is not incidental. When the AIDS epidemic exploded, one of the first responses to it, both within and outside the queer community, was to urge gay men to stop having sex and to enter into monogamous relationships. Even after the specifics of AIDS transmission became known (sometime in the mid 1980s), much AIDS education focused not on simply promoting "sex safe" practices, such as condom use, but on curtailing sexual experience altogether. For many gay male commentators, such as Larry Kramer, Bruce Bawer, and Gabriel Rotello, the curtailment of sexual activity was the only "cure" for the AIDS epidemic.

When the same-sex marriage debates began to escalate in the early 1990s, the "pro-marriage" arguments became eerily similar to the previous arguments about AIDS. Marriage, many of its proponents argued, would help end the AIDS epidemic because it would give gay men the option - even the mandate - to pair up and be monogamous. As noted legal scholar and distinguished same-sex-marriage proponent William N. Eskridge Jr. wrote in his 1996 book The Case for Same-Sex Marriage: From Sexual Liberty to Civilized Commitment: "Human history repeatedly testifies to the attractiveness of domestication born of interpersonal commitment, a signature of married life. It should not have required the AIDS epidemic to alert us to the problems of sexual promiscuity and to the advantages of committed relationships. A self-reflective gay community ought to embrace marriage for its potentially liberating effect on young and old alike."

When I talk to my gay and lesbian students and other young queer people, there is no doubt that they are in favor of marriage equality. It's a no-brainer: Why shouldn't there be equality under the law? But very few of them actually seem interested in getting married, now or later. That's true of both gay men and lesbians, although the women are more inclined to consider marriage in the future. Such ambivalence stands in sharp contrast to my heterosexual students, many of whom expect to get hitched sometime in the near future and some of whom have even made plans to do so after graduation.

So what's the problem? Young queer people are growing up and trying to figure out what sex and relationships are all about. It is both an exhilarating process and a confusing one. I think most young people know that there are two paths - parallel, but quite different - that will help them gain the life experience they need to find a happy, contented, exciting adult sexuality. The first is a vibrant, active, experimental, and wide-ranging sex life with a number of people, through which they will start that endless journey to better and more fulfilling sexual experience. The second is an ongoing, maturing relationship with one, or maybe more, persons, through which they will discover not just the moral pleasures of an expanding emotional relationship, but the physical pleasures that come with it. Most of us, excluding, of course, the president and a significant part of the religious right, which favors abstinence-only sex-ed, have come a long way from Why Wait Till Marriage? and Evelyn Millis Duvall's advice that both women and men benefit from premarital chastity. We know that people get better at sex not only by having a range of sexual experiences, often with different people, but by thinking and talking about sex - about what they like and want and expect and can give. That is the conversation that gay men and lesbians as a community are not having now, and that is being stifled by the power and the enormous consequence that the same-sex-marriage debate - drained of sex - has assumed in our politics and lives. •

Michael Bronski's last book was Pulp Friction: Uncovering the Golden Age of Gay Male Pulps (St. Martin's Press, 2003). This article originally appeared in the Boston Phoenix.