| A vibrant cowboy rallies his herd under the "Saga of the Seven Flags" and the Randolph Air Force base tower on the eastern wall of the Alameda Theatre. A new Smithsonian study confirms the importance of the black light murals in a brief, but brilliant, artistic trend of the '40s and '50s. (Photo by Mark Greenberg) |

It's almost painful to look at the four large, ragged holes that mar the blue plaster of the Alameda Theatre's eastern ceiling and wall. Even in the black light that brings out the glowing murals for which the Alameda is once again famous, dark streaks caused by roof leaks bleach the images of oil derricks and gleaming buildings of the future. A large vertical scar marks the seam where partitions split the 2,400-seat auditorium into a movie triplex during the theatre's decline.

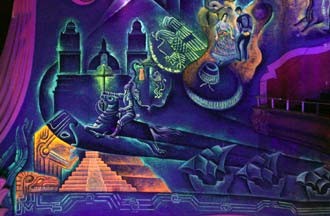

Despite the water damage and a half century's accumulated grime, a vibrant cowboy clad in an orange shirt gallantly waves his hat beneath the seven flags of Texas. Across the way, on the western wall, his Mexican counterparts are frozen in a dance, surrounded by an Aztec temple, Spanish ships, and other images from their country's last 600 years.

A recently completed study of the paintings by the Smithsonian Institution confirms what those lucky enough to have seen the murals suspected: The artworks are an international treasure, possibly the largest existing example of a brief trend in theatre design that flourished in the '40s and '50s, during the last hurrah of the great movie palaces. The Smithsonian study will be presented this fall at the conference of the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works at the new Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, a prestigious gathering of art conservators from around the world.

The Alameda opened to the San Antonio public on March 9, 1949, with a gala dedication that included performances by Prima Donna Soprano Josephine Lucchese, sister of the theatre's builder and owner, G.A. Lucchese, who operated several cinemas in the city. Lucchese conceived the theatre as a tribute to the city's Mexican-American population, which was confined to segregated seating in San Antonio's other premier entertainment facilities. During its heyday, the Alameda showcased Spanish-language films, vaudeville acts, live music, and dance.

In his statement in the dedication booklet, Lucchese wrote that he hoped the Alameda "would be a permanent symbol of good faith and understanding between the Latin-American and Anglo-American. It should become a meeting place for the two peoples where they might share and recognize two different cultures."

| The artworks are an international treasure, possibly the largest existing example of a brief trend in theatre design that flourished in the '40s and '50s, during the last hurrah of the great movie palaces. |

But for every known fact about the mural's composition, or bit of lore about the theatre's history, an equal number of questions remain. No one knows, for instance, exactly what the colors in the murals looked like when they were first painted. Black light painting has just begun to receive attention from art conservators, but it has not yet been studied in great detail. Conservators first turned their attention to the preservation of works by Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, and their contemporaries, but the rediscovery of interior design with the paints has generated immense excitement.

"I don't think it's something people knew they knew about," says Sarah Eleni Pinchin, a paintings conservation fellow with the Smithsonian who co-authored the study of the Alameda. When she questioned members of her parents' generation, though, they would say, 'Oh, sure, we remember that.'

One of the reasons the Smithsonian is so excited about the Alameda's treasure trove is that it offers an unparalleled chance to study the earliest days of the medium in a unique setting. Even during the height of black light decorating in theatres, many venues appear to have ordered pre-fabricated murals on canvas, rather than commissioning original works on plaster. The only other known venue with comparable images is the Linda Vista Theatre in Mexico City, built in 1942 and featuring fluorescent dancing couples, but one of the Institution's hopes is that publicity and attention for this neglected tradition will bring new examples to light.

According to Daniel Hagerty, executive director of Centro Alameda, the umbrella organization responsible for building the Museo Americano in Market Square and the renovation of the theatre, until recently it was thought that, unless carefully preserved, fluorescent paints might have a lifespan as short as 10 years, so it is an exciting puzzle that these murals have survived so long under adverse conditions.

San Antonio architectural firm Killis Almond & Associates is overseeing the building's preservation and renovation. The initial cost of renovating the Alameda so that it can be used for film screenings and small-to-midsize theatre productions has been estimated at $5 million, but the expense could increase depending on the money and effort put into preserving the murals. It's not known whether there are any restoration artists with experience in recreating the hues and effect that were achieved through carefully layering the fluorescent pigments. "Artists and decorators had to forget the old color rules and learn new ones," notes a theatre catalog from the period. "In fluorescent black-light art, blue and yellow do not make green ..."

But, says Pinchin, "I'm convinced that there are people who are very talented and who will do a very good job." She adds that the opportunity to work in an emerging and fairly rare field will be very enticing to professional conservators.

Museo Americano is an affiliate of the Smithsonian, which has brought the resources of the Institution to the theatre as well. Centro Alameda receives no direct funds from that relationship, but one of the great boons has been the detailed study and analysis of the murals conducted by the Institution's staff. During the course of last winter and summer, a team of conservators and chemists analyzed the composition and condition of the pigments and the underlying plaster and researched the development and use of black light paints.

Among the team's discoveries were that the Alameda's interior walls and ceiling are made of a special light-weight plaster blend that probably results in enhanced acoustics. The technical examination report notes that unofficial tests of the auditorium's acoustics "have exceeded expectations," which is very exciting for Hagerty, who envisions full-scale opera and dance productions in the theatre once a planned stage expansion is completed.

| A detail of the western wall of the Alameda's black light murals reveals Spanish ships on their way to conquer the Aztec empire as Cortez looks on. The western wall is better preserved than the paintings on the eastern wall, which have suffered from extensive roof leaks. (Photo by Mark Greenberg) |

Fluorescent paints were tested and used extensively with aircraft during World War II. Beginning in the '30s, fluorescent dyes began to be used in the performing arts. Switzer Brothers, Inc. of Ohio, a major producer and supplier of black light pigments for the military and public, was the source of the paints used in the Alameda. Hagerty has approached the Switzer family, and the Day-Glo Corporation to whom Switzer sold their business, to seek help in recreating the "carnelian rose," "topaz," and other colors used.

In addition to chemical formulae and ultraviolet analyses, the Smithsonian report also offers a bounty of less technical information. The Alameda's foyer, for instance, is similar in layout and decoration to the entrance of the Chapultepec Theatre of Mexico City, built in 1944, and may purposely echo its design.

Under the watchful eye of "The Spirit of the Dance," the lithe aluminum figures sculpted by Teran for the Alameda's foyer, Hagerty plans the theatre's rebirth. He hopes the Smithsonian report will draw more attention, and more funding, to the Alameda's cause. While the theatre's complete renovation will follow the 2005 opening of the Museo Americano, Hagerty is currently working to raise $250,000 for the conservation conference in Bilbao. The monies will be used for additional work on the murals for presentation at the conference, an investment that could dramatically support the effort to preserve this priceless piece of Latin-American and architectural history. •