|

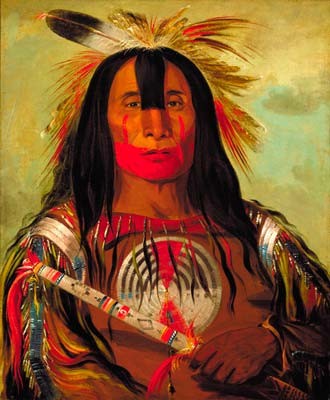

The story of the American Indian told twice by eyewitnesses and once by the heirs When painter and amateur ethnographer George Catlin began to tour his Indian Gallery in the eastern United States in 1837, he often invited Native American warriors and chiefs to appear and vouch for his accuracy. Whether the famous guests, including the Sac Chief Black Hawk, who endorsed his veracity were free of influence themselves it's hard to say; prominent American Indians circulating in white East Coast culture at that time were often current or former prisoners of war, or on missions of trade and appeasement. Nonetheless, Catlin's reputation as a faithful chronicler of the twilight of the North American Indian is largely unblemished. His original body of work, more than 400 portraits of the Plains Indians from North Dakota to Oklahoma created between 1830 and 1837, was a labor of love born of the Enlightenment ideal of the Noble Savage - virtuous man uncorrupted by civilization. Many of Catlin's paintings are familiar as the templates for our images of the continents' original inhabitants: The full headdress and decorated tunic of the Mandan chief Four Bears; the Seminole chief Osceola in opulent Western-influenced dress shortly before his death. A selection of these paintings, which were usually begun in the field and completed in a studio, is touring the country courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (which holds the vast bulk of Catlin's first series) and is currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Accompanying the paintings are some of the artifacts that Catlin collected and exhibited with his work to support its stature. We can shake our modern heads at Catlin's shameless romantic projection - the lawyer-turned-artist presented the Northern Plains tribes as nature's royalty and in his writings made frequent comparisons to the ancient Greeks and Romans - but we also have to acknowledge his sincere advocacy for their social status. He originally gained access to the Western tribes through General William Clark, the famous explorer and first federal overseer of the much-botched Indian "affairs," but Catlin grew increasingly critical of U.S. policy toward the American Indians.

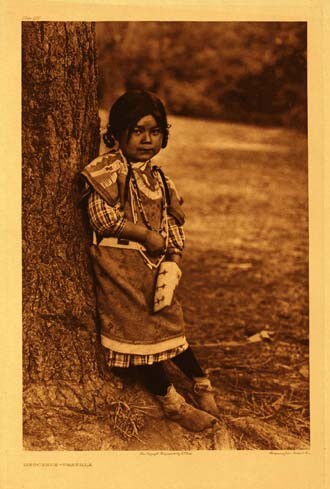

As Catlin's paintings and artifacts attest, the tribes with whom he interacted - some 50 in all - were still using the traditional quills to augment their dress and accessories. By the time the photographer Edward S. Curtis came through 70 to 100 years later, shiny glass seed beads ornamented cradle boards, vests, and bandoliers with little quill work, and European-style fabrics were in wide use; these surface changes represented a deeper truth: little remained of the traditional Native American way of life. The transition is evident in the dark, almost wine-colored photogravures on display at the San Antonio Museum of Art through January 9, 2005, accompanied by (spottily relevant) artifacts from the Witte Museum's collection. Much of the ritual and costume that Catlin recorded in its twilight was no longer in use by Curtis' day, but Curtis often staged his photographs, asking his subjects to don old ceremonial headdresses and robes. Most infamously, he faked an entire ceremony on film with recreated masks. This practice, and others, has left Curtis' reputation in sorrier shape than Catlin's, and the contrast between their legacies highlights one of the major developments in 20th-century culture: " ... the transformations associated with modernity," write the historians Vanessa Schwartz and Jeannene Przyblyski, "can be generalized as having been waged along a cultural axis between investment in the positivist certainty of visual facts and ambivalence regarding the illusiveness of mere appearances." Can we trust the camera lens? Only so far, Curtis tells us, but his subjects' faces are real. Curtis has more recently been academically rehabilitated as a means to talk about how we define the "other." Both artists romanticized the North American Indian and, in their portrayals, often isolated them from the cataclysmic change in which they were swept up, presenting them as timeless archetypes. Whether or not it was intentional, this reinforced the idea of the immutable separateness of indigenous culture even though, like many cultures in conflict, the native population had a long history of interaction and even accommodation with the European invaders. It also subtly reinforced the then-accepted notion that primitive culture, no matter how admirable, must inevitably make way for the progress of civilization. Curtis is additionally accused of contributing to the infantilization of Native Americans, an attitude that legitimized the parisitic Bureau of Indian Affairs. (To this day, the BIA has not accounted for millions in revenue from Indian lands and a host of other violations of its responsibility.)

Fortunately for Texans, the Catlin and Curtis exhibits arrive just after the grand opening of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington. Directed by a Native American, and including contemporary Native American art and craft, the Museum responds to another point of contention between the indigenous population and European culture at the point of contact: the West's reliance on empiricism - sight in particular - and its attendant "facts." As has been widely noted by critics, the new museum eschews such information as how human ancestors came to this continent in favor of Native American creation myths. It may make some visitors uncomfortable that the Museum of the American Indian is not what we have learned to expect of museums: catalogs of European assimilation and mastery of a subject, be it a people, an ancient civilization, a species, a science. It upends the old saw that history is told by the winners. "Visitors will leave this museum experience knowing that Indians are not part of history," founding director W. Richard West, a Southern Cheyenne, says in the official press release. "We are still here and making vital contributions to contemporary American culture and art." And suffering from the worst health and life expectancy in the U.S., we should add. Modern-day Native Americans have the right to tell their story the way they wish it to be told, but it, too, will inevitably be a story more than a record, because the arc of the narrative has been pre-determined by the storytellers, much as it was in Catlin's and Curtis' day. Only now, the story is about the persistence of cultural remnants against the odds rather than Manifest Destiny. It is worth noting that the introduction to the Curtis exhibit softpedals the destruction of the Native American population. No numbers are given to tell us how many indigenous peoples populated the country before the Europeans arrived; there is no real accounting of battles, disease, land grabs, and incarceration. The facts can tell us many damning things: Curtis' photographs were largely commissioned by the magnate J. Pierpont Morgan, who directly benefited from the removal of Indians from their lands. They also leave us with some puzzles that can't be solved in hindsight: Curtis bought cattle to feed the Sioux at Pine Ridge Reservation during a famine, but he also bought Indian land after the Dawes' Act violated tribal ownership. Naked opportunism? Useless sentimentality? Why did Catlin sell prints of his famous portrait of Osceola after the chief's death rather than give the original to the U.S. government, which had commissioned it? Crass capitalism? Contempt for the federal bureaucracy? We can't make sense of these actions without supplying our own, modern narrative and so, while we can recreate a Catlin, a Curtis, or an Osceola, that serves our current national story, we can never recover the past. Yet, these images, whether reproduced through a mechanical eye or a human lens, offer us a glimpse of what was once the truth. • By Elaine Wolff

|

Tags:

KEEP SA CURRENT!

Since 1986, the SA Current has served as the free, independent voice of San Antonio, and we want to keep it that way.

Becoming an SA Current Supporter for as little as $5 a month allows us to continue offering readers access to our coverage of local news, food, nightlife, events, and culture with no paywalls.

Scroll to read more Arts Stories & Interviews articles

Newsletters

Join SA Current Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.