Speaking to the Current in September about adjustments made upon the appointment of Riley Robinson as executive director, Archives & Communications Director Scott Williams said, “The first thing Riley said to us when he became the new director was, ‘Artpace isn’t going to turn people away anymore. If we’re here, we’re open.’ … Even if it’s not during our ‘hours,’ we will not turn you away if you come to the door wanting to experience art.” Additionally, Artpace has made Open Studios a new tradition, offering the public a “behind-the-scenes look into the artists’ process” as they build exhibitions for the esteemed International Artist-in-Residence (IAIR) program, which annually invites three guest curators to each select a trio of artists — one from Texas, one from elsewhere in the U.S. and one from abroad — to “live and create art in San Antonio for two months.” While some might argue that sneak peeks are essentially spoilers for all the potential drama of an exhibition reveal, this sort of personal access to artists in their element can demystify certain complexities of contemporary art and even debunk some of its lingering pretensions.

Held on the evening of October 16, the Fall 2018 Open Studios welcomed guests into the workspaces of artists Ana Fernandez (San Antonio), Alice Khalilova (London) and Clifford Owens (New York), all of whom were selected for IAIR by British curator, writer and radio producer Morgan Quaintance. While most who follow the local art scene will already be acquainted with Fernandez — the proprietor of the wildly popular raspa truck Chamoy City Limits who expertly captures the spirit of San Antonio via watercolors based on her own moody photographs of homes, street scenes, gas stations and taco joints — the other two residents are far from familiar names in these parts, despite considerable successes in their home bases and beyond. Khalilova, who identifies as an “Anglo-Russian multimedia artist,” works between installation, sculpture and video, often challenging concepts associated with representation, objectification, technology and desire. As for Owens, his work relies on photography and interactive performance but also encompasses conceptual processes and works on paper. In terms of aesthetics, approaches and mediums, the three don’t share immediately identifiable commonalities but they still seem to mesh effortlessly. As the only local in the bunch, Fernandez rose to the occasion of showing Khalilova and Owens some of the less-obvious aspects of San Antonio.

During the Open Studios, I spoke with this oddly dynamic trio about human statues and the term “eat shit” (Khalilova), contemporary applications of the ancient medium of fresco (Fernandez), “conceptual conceit” and performance’s unusual ability to spark bonds between strangers in the same audience (Owens).

So, I read your bio and also searched online for your previous work. Technology, spirituality and philosophy: can you tell me a little about how those concepts intersect in your work?

That’s kind of maybe [more relevant to] my old work. I’m interested in how we approach desire and search for meaning today in a world that’s constantly being displaced by another medium [of] communication — not so much social media … but accessing a feeling [that] goes through the screen … how we approach desire and displace desire through the screen ... in terms of the capitalist system that we’re in. That’s why I’m interested in [the idea of] the human statue — someone becoming an object [or] being forced to become an object, their labor is objectified. And those lines are completely blurred with what we see as objectification through pornography or extremely violent films.

Do you have a clear vision for your completed exhibition here?

Seventy-five percent yes.

So part of it’s developing organically.

How I work usually is I research months and months and months, and write. And then all those ideas kind of come together. But since I’ve arrived here, I’ve had so many new ideas, about so many different directions I want to bring in. So it’s been a bit of a dance, which has been really fun. I’m going to be taking some risks with this show, which I’m very excited about.

The new ideas you’re getting, are those directly related to San Antonio or your experiences here? Or just how you’re seeing your own work develop?

Maybe America. Well, more specifically San Antonio, but being in America — especially being Russian — and at this time, what’s happening. Yeah, it’s influencing me and making me look at certain political issues that I may not bring out obviously in the work but it’s making me look at them in a slightly different way.

And so the 75 percent that you’re clear on, we’ve got a human statue, but what else can you tell us about what you’re working on?

You can say that rocks are involved. You can say that physical activity is involved. And climbing is involved. [There’s a video that’s] a direct reference to San Antonio, a direct love letter in that I kept hearing this phrase “eat shit.”

Like when you fall?

[Yes], I hear it from skateboarders all the time. [The video] was pretty physically intense, I’ve got to tell you.

One of your projects I found online, and it may be an older one, is about making gazpacho with fake nails.

Oh, yeah, that’s really old!

So how did that come about?

It kind of came about from going to the Caribbean. It’s actually quite related to this in a way. I was thinking about labor and femininity. I guess coming from a position of being an Eastern European woman and not having that position in society — of being the cook, being the cleaner — but then going to the Caribbean and meeting a lady who was essentially cooking for my family. And we [formed] this bond and she gave me that recipe for gazpacho. It’s super-authentic — she was Spanish but living in the Caribbean. So I wanted to kind of play around with the extremely fake idea of femininity together with what is the labor of women across the world.

It somehow reminded me of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

Yes! Good! Good, I’m so pleased! [Laughs.]

What’s the social dynamic been like with the three of you?

Absolutely amazing. Ana [Fernandez] is a saint.Are you the youngest?

I’m a lot younger. I’m the baby. I think I might be one of the youngest residents here ever.

Are Clifford and Ana acting like big brother and big sister?

Ana has been showing [us] everything. And if I’m scared, I’m like, “Ana!” Clifford and I have a great rapport as well. It’s been great.

So you’re having fun.

I’m having the best time. Too good of a time.

Will we be seeing a different side of your work with this exhibition?

A little bit, yeah, because I’m doing some fresco work – which, with the fresco, because the binder’s been taken out of the pigment, it’s like I’m backing into a sculpture. It becomes more sculptural just by definition [and] it opens up a lot more possibilities.

What inspired that?

Well, when I went to my summer program at Skowhegan [School of Painting & Sculpture], that’s probably the … class it’s [best] known for — they teach you fresco if you want to learn it. And so I learned it and I liked it. My job duty was to work in fresco because every [resident artist] has a job to do. And so I had a catering job and I transferred into fresco because I liked it so much.

So the one you just showed was small, but are you thinking of doing large-scale frescoes here?

Possibly, I might, but I want to finish the watercolors first. It really depends. I want to [make] it more object-oriented. I like the sculptural element of it, to build it out using cement … and found objects. My grandfather used to work with cement so I’m using some of his tools. And the one thing I wanted to do is — I don’t know if I’m going to do it — is make some chili-powder pigments and natural pigments with the fresco because it kind of combines my grandmother’s work and my grandfather’s work. I want to do some experiments, but I think that I’m going to be using some found objects for sure.

The large pieces we’re seeing here are all watercolors?

Two are large-scale watercolor gouaches and one is an oil.

And are the scenes depicted from recent photographs? And are they in San Antonio?

These are all recent shots. One is in Corpus, the one with the convenience store, and I’m kind of playing with the scale, more of a human scale, to where it’s more actual size. And having these big walls for the watercolors is cool — just to have a giant watercolor, just to be able to feel like it’s more to a person’s scale. And like this lady, I liked her bedazzled jeans. And I was like, I think I want to paint her.

So you’re working on all these paintings at the same time versus completing one and moving onto the next one.

Yeah, I work on — I always work like that. And then at the end I tie them together.

As a local, how responsible do you feel for Clifford and Alice to have an authentic San Antonio experience?

Only to an extent. I feel like I’m just one person, so I would encourage them to get out and meet other people.

Right, but you are sort of showing them around.

Oh, yeah, for sure.

So what can you tell me about where you’ve taken them and what y’all have done together?

Well I took them to Patricia Ruiz-Healy’s opening [for the exhibition “Made in Mexico”]. I took Alice to Papa Jim’s Botánica because I had tripped and twisted my ankle outside, so I was like, we need to sage [the area]. We go to H-E-B a lot and Walmart. I took [Alice] to Walmart; she’d never been to a Walmart, and I felt like she needed to go to a Walmart just to get an idea — take the temperature of the society. Every place has their own Walmart and every Walmart is a sampling of people in the city. We’ve been to openings, a couple of parties … This is [Alice’s] first time in middle America. We’re going to go to a gun shop, because she wants to see a gun shop.

How did the San Antonio version of your Photographs with an Audience performance series go?

It went really well and I am exceedingly happy with the outcome.

Will your exhibition rely heavily on those images?

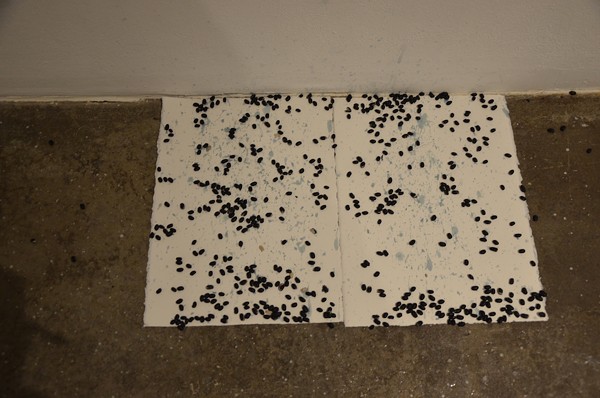

The way I’m thinking about the exhibition and the residency is sort of three parts: Photographs with an Audience — San Antonio; the other part is a body of color photographs that I made between 2017 and 2018, so a whole calendar year. The third part is works on paper; and they’ll include coffee and Vaseline on watercolor paper but also a suite of works on paper that I sort of describe as the outcome of an action or a kind of gesture. So I’m thinking about acting upon these pieces of paper [rather] than it being proper drawing. In other words, there’s a piece on the floor, these two pieces of watercolor paper, and so I soaked some black beans and tossed those black beans across the table so that they would hit the wall. And then they’ve been there on the floor for about 24 hours. So this is kind of an example of a work on paper that the image is produced by a gesture, an action on the paper somehow. I don’t want to say a kind of “performance drawing” but a performance-based work on paper.

No, not at all. It’s going to be an exhibition of photographs mostly and then the works on paper. The only performance I did here was Photographs with an Audience — San Antonio, two nights. The second night was really, very intense. It was really quite moving.

Can you tell me about any of the specific results?

It’s so interesting. I think with Photographs with an Audience, I mean, this is the eighth iteration of the project since 2008. I think the best witnesses of the performance are the audience — the people who were there. So I can kind of give you a conceptual framework for the project. But I think the affect of it is mostly felt by the people who were in the room. And there’s a way in which what happened in the room is only between the people who were there. So there are some details that I wouldn’t want to disclose here.

Because it won’t translate necessarily to another audience?

Exactly. And the photographs necessarily fail to do that as well — but that’s the conceptual conceit of the project.

There’s a mystery to it.

That’s right. What are the limitations, what are the failures of documenting a live performance? I’ve always been interested in that. But since I’ve been here, already one person who was at the Saturday performance told me that he made a new sort of friend out of the performance who shared a commonality, a common experience. He and that person are in conversation and they’ve become friendly. And this is what it’s always been about.

So do you approach Photographs with an Audience with any particular script in mind or do you let the audience kind of determine which direction it goes?

The performance is definitely structured. It has to be, so I know beforehand what the prompts will be. For example, one thing I did in the performance is talk about when I arrived here in San Antonio, at the airport there were advertisements and kiosks, etc., claiming San Antonio to be the Military City. So the prompt was, “Who here has served in the military or is in a military family?” And a number of people stood up. And weirdly of course, that would never happen in [the] New York art-world scene. I sort of like that. So it progresses from there and certain things come up. There was a moment on Saturday when a woman needed to sort of have a space, a place to disclose some things to the audience. So I allowed that and it was very powerful and very moving and very courageous.

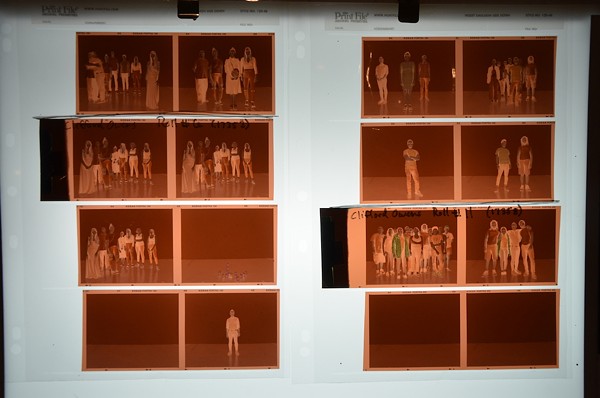

Was it videotaped as well?

No, I don’t videotape — only photographs, only film. Not digital, just film. So what I have here, these are rejects, but I sent the frames, the images that I like, and those are being scanned in New York now. And [film] is so important to the project; it’s always been shot on film.

I did a random Google Image search for you and two things that I noticed from your previous performance work is kissing and nudity. Is there anything you can say about that?

I don’t talk about either anymore.

Get our top picks for the best events in San Antonio every Thursday morning. Sign up for our Events Newsletter.