Cine en el Barrio

La Onda Chicana (1976, 18 min.)

Chicano Love is Forever (Amor chicano es para siempre) (1977, 92 min.)

$6

2pm Sunday, July 17

Guadalupe Theater

1301 Guadalupe

(210) 271-3151

guadalupeculturalarts.org

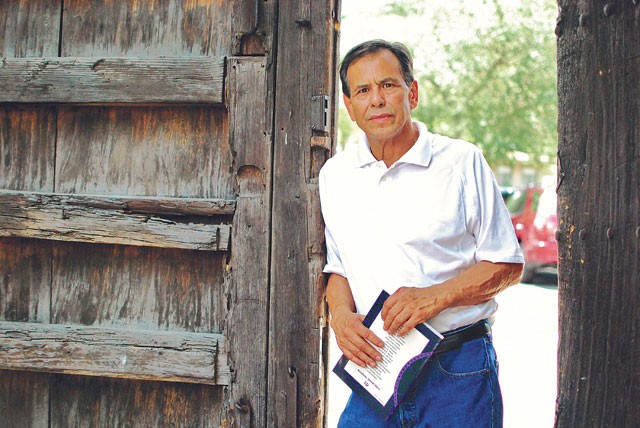

It’s easy to dismiss the films of Efraín Gutiérrez. His movies are rough, unpolished, and lacking those things cinema experts consider, well, good. If Ed Wood was “the worst director of all time,” you can almost say Gutiérrez is a Chicano Ed Wood with a political conscience — bad acting, weak writing, and lousy camera work. Gutiérrez knows it, but he smiles and takes no offense.

“Three!” he says, holding up three fingers on his right hand. “Three takes! I never took more than three takes!” He’s not bragging about it, but he’s not about to apologize either. Time proved Gutiérrez right. Despite countless limitations, his films are so raw and honest that Gutiérrez became the first Chicano filmmaker with three movies in the UCLA Film and Television Archive (the world’s largest university-based media archive), which restored his films. Two of those movies will be shown at the Guadalupe this Sunday (see info box), another reminder that Gutiérrez has earned his place in the history of Chicano — scratch that — in U.S. film history, thanks to movies he did on shoestring budgets and on his own terms.

“I was the first independent,” he says. “Nobody wanted to work with us [in the mid-’70s], so we produced it ourselves, we raised our own money, we acted, we directed, and the stories were something that we knew was going on at that particular time. Ninety percent of the cast were not actors and I didn’t come about wanting to be an actor at first. I was kinda pushed into that role.” But he went ahead and did it, and he did it before anyone else.

Of course, that legacy was virtually ignored for years. It took San Antonio journalist, poet, playwright, and long-time Current contributor Gregg Barrios to raise it from the depths of cultural amnesia. In the book Chicano Cinema: Research, Reviews, and Resources (edited by Gary Keller), it was Barrios who set the record straight. “It must be pointed out that single-handedly Efraín created the first real Chicano cinema,” Barrios wrote in his essay, “A cinema of failure, a cinema of hunger: The films of Efraín Gutiérrez.”

“Yes, [California filmmakers] Jesús Treviño and Moctesuma Esparza … might feel they alone have pioneered Chicano filmmaking. Yes, they were among the first, but it was Gutiérrez whose first feature [Please Don’t Bury Me Alive!] was shown theatrically with success (especially in the Southwest) in 1976, prompting Azteca films to buy the distribution rights for Spanish-language circuits in the United States and Mexico,” he wrote

Then came La Onda Chicana (1976, a short), Chicano Love is Forever (1977), Run, Tecato, Run (1979), A Lowrider Spring Break En San Quilmas (2000, his first “entertainment” film after three political ones), and the family-oriented Barrio Tales: Tops, Kites, and Marbles (2008).

“I think my strength was that I was able to put something together and finish it with minimal costs,” Gutiérrez told the Current. “We weren’t filmmakers, we weren’t camera men, we’re weren’t technicians, we had no equipment, we had no money, but we had something to say.”

When he wrote his essay, Barrios was also well aware of Gutiérrez’s limitations and strengths as an auteur. “By refusing to give us the typical Cenicienta [Cinderella]-leaves-the-barrio-for-the-big-time tale, [Gutiérrez] is stating a reality that many of us have forgotten. … For every Chicano who gets educated, who aspires to greater heights, who leaves the streets, there are hundreds more who never leave … He has given us a cinema of hunger … and he has taken more chances than any of our other filmmakers has.”

The two films to be shown at Guadalupe have an undeniable historical value. La Onda Chicana was supposed to be a feature film documenting a mammoth Chicano music concert at Port Lavaca on July 4, 1976. But the 16mm camera broke and only Little Joe y La Familia, Snowball and Company, Los Chachos, and La Fábrica made it to the final 18-minute cut. Chicano Love is Forever is a Gutiérrez-style love story: a tragic Chicano love triangle.

Each of his movies was supposed to be the last, but he’s always managed to make one more. No longer.

“No more movies for me,” Gutiérrez said. “I feel old, and most of my friends that worked with me in movies are all starting to pass away.” Most notable is the death of former partner Josie Faz, the mother of two of his daughters, who passed away July 4 of heart failure. She was a co-star in his first film and did camera work and was executive producer of Run, Tecato, Run. “She was a true pioneer.”

But there is another reason — beyond the elusivity of commercial success — that Gutiérrez is walking away from movie-making. “I was upset with some of the artists that I felt weren’t getting involved with the [Chicano] movement,” he said. “That was the reason I started in the first place: I was frustrated with our own civil rights movement and channeled my anger into making a movie. So we did what we did because we thought it had to be done, and I’m very proud of the work that we’ve done. If only people understood what we had to work with.” •