The movie, which features Tejano music icons including Flaco Jiménez and Lydia Mendoza, was primarily filmed in San Antonio. As such, it deserves credit for introducing conjunto, South Texas’ homegrown musical form, to much of the outside world.

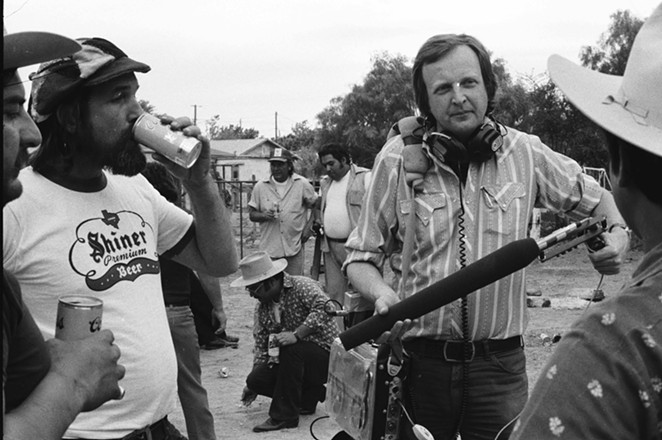

Co-directed by film legend Les Blank and Chris Strachwitz, founder of groundbreaking roots music label Arhoolie Records, Chulas Fronteras — which translates to “beautiful borders” — is a moving and culturally significant time capsule of Tejano music and border culture. In testament to its cultural significance, the movie was entered into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 1993.

“What’s beautiful about that film is its vibrancy and the performances,” said Hector Saldaña, curator of Texas State University’s Wittliff Music Archives. “There is a reverence, there is a sense of respect and love of the culture. They weren’t filming it to put it down or ghettoize it. They were holding it up and saying, ‘My God, this is beautiful!’”

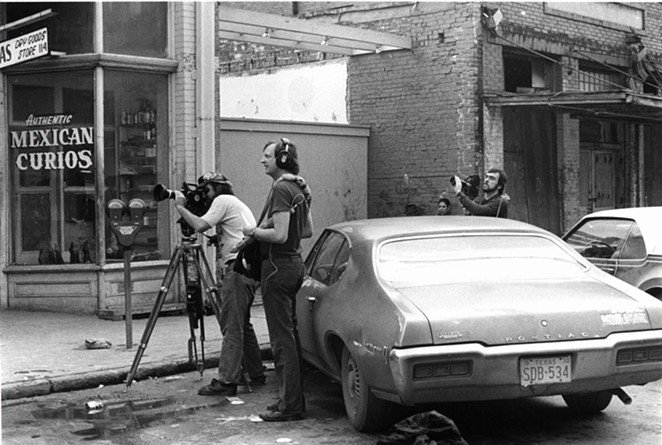

Chulas Fronteras employs Blank’s trademark “tone poem” style, largely eschewing the standard talking-head documentary format. Instead, it dives straight into the world it seeks to depict. The lens often draws back from the musicians to see everything else happening around them.

Blank, who died in 2013, received the American Film Institute’s Maya Deren Award for outstanding lifetime achievement for his work as an independent moviemaker.

“It shows a San Antonio and a West Side that don’t exist anymore. And that’s one of the coolest aspects of it,” added Saldaña, a former Express-News writer and frontman for long-running garage rock band Krayolas. “The vibe of San Antonio was so different then, in the ’70s. It was really wide open.”

One by one, the documentary introduces the musical giants who helped define Tejano and Norteño music. Along with the aforementioned Jiménez and Mendoza, viewers encounter Narciso Martínez, Santiago Jiménez Sr. and Jr., Los Alegres de Teran, Los Pingüinos del Norte, Rumel Fuentes, and San Antonio musical giants Jose Morante and Salomé Gutiérrez. The camera explores an independent and thriving South Texas music culture that includes record shops and homegrown recording studios, even a small-scale San Antonio record-pressing plant.

The significance of the film, which was digitally remastered and released on DVD and BluRay in 2018, isn’t lost on Strachwitz.

“It really flows, doesn’t it?” he asked during a recent phone conversation. Strachwitz, who just turned 90, is still a master storyteller. And Chulas Fronteras is certainly evidence of that.

‘The beauty of a culture’

Like many of America’s regional musical styles, the one created along the Texas-Mexico border is a unique hybrid found nowhere else — the sound of Czech and German polkas and accordions fused with Mexican and indigenous culture and the bajo sexto, a distinctive 12-string Mexican instrument in the guitar family.

“We created a very unique original American ensemble, called ‘conjunto’ north of the border and ‘Norteño’ south of the border,” said Juan Tejeda, a former Palo Alto College professor and activist whose resume includes helping launch the Tejano Conjunto Festival and heading the Xicano Music Program at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center. “We are this hybrid, this fusion, and our music and culture reflects that. We are this border people ... that transcends borders.”

To that point, Chulas Fronteras depicts not only the region’s music but the Mexican American border experience in its totality. The viewer gets an up-close look at migrant workers, racism, police brutality, dances, weddings, delectable food and even cockfighting.

“It blew me away,” Tejeda said of his first viewing of the documentary. “It was the first time it had been put out like that. And when it came out, it had a tremendous impact — it reverberated. Not just in the film or music industry, but throughout the Chicano community. ‘This is what we need to see! Something positive, not this gang shit that’s always being depicted.’ It showed the beauty of the culture.”

The Strachwitz story

The making of Chulas Fronteras begins with one unlikely man: Strachwitz himself.

A German immigrant fleeing the invading Russians at the end of World War II, Strachwitz immigrated to the U.S. in 1947 and lived with a great aunt in Reno. He was a stranger in a strange land, but quickly became enamored of U.S. regional music styles — conjunto, hillbilly, blues and jazz — emanating from XERB, one of the high-wattage “border blaster” radio stations operating from Mexico.

It was a breath of fresh air.

“In most of Europe, opera and classical music was so embedded in the popular culture, and they had no local dance music like people have here,” he said. “They listened to war marches and pop music, which was horribly schmaltzy.”

After working for several years as a schoolteacher, Strachwitz couldn’t resist the lure of the music world. The folk scene of the early ’60s, inspired by folklorist Alan Lomax, sought to document America’s regional styles — the “old weird America,” in the words of critic Greil Marcus — and so did Strachwitz. He joined other musical obsessives sniffing out and chronicling undiluted regional folk styles before they vanished. Think Indiana Jones with a tape recorder instead of a bullwhip.

Thus began Strachwitz’s many forays into Texas, first focusing on African American blues and Creole music in East Texas and Louisiana where he helped “discover” and bring attention to Mance Lipscomb, Lightnin’ Hopkins and Clifton Chenier through his then-fledgling Arhoolie label.

During his early 1960s trips from California to Houston, Strachwitz would inevitably drive through San Antonio, and the conjunto and Norteño music playing on the radio caught his ear. Of particular interest was the use of accordion, originally a German instrument, and the duetos, or tight vocal harmonies.

“I quickly found out that I liked music with accordion,” Strachwitz remembers. “I became aware of these myriads of labels that sprung up in South Texas since the late ’40s — Rio, Falcon, Ideal. I heard the music, and I became very fond of it.”

Digging for the Frontera collection

That music ended up being Strachwitz’s first lure to San Antonio for a proper visit.

During the ’50s and ’60s, as 33 and 45 rpm records dominated the marketplace, many stores and juke box operators dumped their now-obsolete 78 rpm discs for dimes. On a tip from Alamo City folklorist Larry Skoog, Strachwitz ended up in a West Side warehouse, sifting for hours through old 78s from the collection of radio station KCOR.

He purchased 1,000 records that day.

“The 78s were heavy,” Strachwitz recalled. “It was probably 500 pounds of records! I was totally dehydrated because it was a hot day, and I was furiously looking for more and more in this mini storage. At one point, a tarantula popped out. I was scared but didn’t drop the records!”

That haul immersed Strachwitz in the regional style of the corrido, a genre of border folk balladry depicting current events and tragic heroes. The songs serve as a “musical newspaper” for border communities. Older corridos depict the assassination of JFK, Pancho Villa’s exploits and struggles against the Ku Klux Klan while new “narcorridos” chronicle the border drug trade.

Corridos date back hundreds of years, descendants of the Spanish “romantic” songs of the Middle Ages, but the form was filtered through the South Texas waltzes and polkas as well as the Tejano experience. The style takes its name from the verb “correr” (to run), referencing the songs’ brisk pace.

Strachwitz continued exploring South Texas border music for another 10 years before deciding to document the scene on celluloid. He and Blank decided to shoot a documentary about the major musical figures of San Antonio, but he hadn’t met them yet. Thus began another sleuthing adventure.

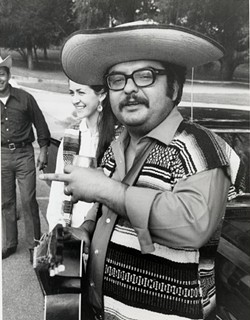

“I first met Fred Zimmerle and his Trios San Antonio. Then I met Salomé Gutiérrez, who founded Del Bravo Records,” Strachwitz said. “I immediately sensed that Salomé was a real character. He was so helpful for the film, tracking down folks, making connections.”

Del Bravo, founded in 1966 and situated on Old Highway 90, is considered by many to be the oldest record shop in Texas. In 2018, San Antonio’s Historic and Design Review Commission designated Old Highway 90 (a.k.a. Enrique Barrera Parkway) as a Cultural Heritage District, making it only the city’s second area to land the designation. Del Bravo is still there — and still slinging vinyl, cassettes and CDs.

Del Bravo is a reminder of the vibrant South Texas musical ecosystem that grew out of the region’s conjunto scene, a network of independent record shops, studios, publishers and promoters.

In the 1920s, northern record labels looked to boost sales by dispatching mobile recording studios to other parts of the country so they could expand into regional styles — among them, blues, hillbilly, Mexican, Cajun and German. These labels would advertise in local newspapers and book all-day sessions with regional musicians. This was still the Jim Crow era, however, which complicated the process.

“In San Antonio, they had to make sure they would allow people of color to come to top floors. In those days, they still had ‘No dogs, no Blacks, no Mexicans’ [signs] outside of businesses,” said Rudy Guitiérrez, son of Del Bravo’s Salomé Gutiérrez. “And back then there was no air conditioning. They were recording onto wax, so if it got too hot ... the masters would melt. So, they had to pick the right seasons ... and the right hotels that would allow minorities inside.”

By the end World War II, big labels ended their regional recording expeditions, leaving an opportunity for local enterprises to release records of their own. Into this gap stepped Armando Marroquín. As founder of Ideal Music in the Rio Grande Valley, many consider Marroquín the first Mexican American studio owner.

“That sounds like a fancy title ... but he was recording in his living room,” Gutiérrez said with a laugh. “But people loved it. And now the jukebox owners had new records to spin.”

Beyond feeding jukeboxes, Marroquin pioneered a new business model, one where Mexican Americans took control of their own music without waiting for major label support.

“We see Ideal as the origin of local record labels here in Texas,” Gutiérrez added. “If he can make it, we can make it.”

Inspired by that success, the senior Gutiérrez started the Del Bravo Record Shop, the DLB record label (along with its 10 sublabels), a recording studio and San Antonio Music Publishers, which grew into one of the largest publishers of Tejano music and possesses one of the largest independent Latin catalogs. Beyond his entrepreneurial activities, he also somehow found time to write more than 1,000 songs.

“He was really there at the beginning of commercial conjunto and Norteño music,” Strachwitz said of Gutiérrez in a 2016 obituary. “He quickly realized the [vitality] of the music of the underclass. He also composed, which was the other amazing thing. The songs had to be in the vernacular so that people liked them, and he knew how to do that. His knowledge of the local language was extraordinary.”

Along with legendary San Antonio producer Jose Morante — whose amiable presence features prominently in the film — and Ideal’s Marroquín, Gutiérrez forged an impressive musical community.

“Those three men together helped each other. Everybody here knew somebody,” the younger Gutiérrez said. “We lent a hand. ‘Why don’t you sell my product in the Valley, and I’ll sell your stuff up here in San Antonio? So, people started hearing all the different styles.”

Meeting Flaco

Also crucial in helping Strachwitz and Blank assemble the musical cast of Chulas Fronteras was San Antonio’s Rio Records.

After a stint teaching electronics at Kelly Air Force Base, Hymie Wolf founded Rio at 700 W. Commerce St. in what used to be his family’s liquor store. During the remodel job, he built a recording studio in a back room of his new record store.

“For authenticity, no other label or producer captured pure cantina music the way Hymie Wolf did on his Rio recordings,” wrote Strachwitz in the liner notes for Tejano Roots: San Antonio’s Conjuntos in the 1950s, released by Arhoolie in 1994.

However, by the time Strachwitz and Blank got around to making their film, Wolf had died, leaving the business to his wife Genie.

“I went to Mrs. Wolf, and I asked her, ‘Who do you think I should be looking for?’ And she came right out and said, ‘There’s a really handsome guy. He’s a really good musician and he’s really gonna go places; he has real charisma. His name is Flaco Jiménez.’”

When Chulas was filmed, Jiménez wasn’t the household name he is today thanks to his subsequent mainstream breakthroughs, including his stint with the Texas Tornados. Though he’d already become a regional star with his hit single “Un Mojado Sin Licencia,” which he performs in the film, Flaco was only beginning his journey into the mainstream. Even so, he’d already met Bob Dylan and other music industry luminaries during the 1972 session for Atlantic Records’ Doug Sahm and Band. During the filming of Chulas Fronteras, he also became close with slide guitar maestro Ry Cooder, who further elevated his career.

“The film brings a lot of memories of my fellow musicians, especially my dad,” Jiménez said in a Q&A following a 2018 Austin Film Society screening of the documentary. “It’s very hard to explain those memories — the long roads and ... flat tires. Homemade trailers, hauling U-Hauls to the gigs, every 30 minutes a blow-out. We carried three spare tires to the gigs. ... Les Blank and Chris Strachwitz managed to put our scene into a film. In some ways, the music has changed — change of instrumentations, too many synthesizers, not the nitty gritty of our kind of music. But ... I’m lucky to still be here.”

Chulas also spotlights Jiménez’s father Santiago Jiménez Sr., another of the true giants of South Texas music, performing with Flaco’s brother Santiago Jr. Those scenes have a particular resonance for Juan Tejeda.

“I come from this tradition,” said the conjunto scholar. “I learned my first polka, which was originally played by Santiago Sr., when I was 9 years old. So, it’s very special to me, those scenes.”

Strachwitz himself has a warm place in his heart not just for Flaco and his father, but for the whole family.

“Puro conjunto is a very limited thing when you’re dealing with a gringo audience,” Strachwitz said. “Flaco has expanded beyond, crossed genres, with the Tornados and Ry Cooder. But I love Santiago Jr., ‘El Chief.’ He’s holding down the tradition, the puro conjunto style. The traditional approach is more limited in its reach, but thank God he’s holding it down.”

For the film’s scenes in the Rio Grande Valley, Strachwitz relied on Ramiro Cavazos, the bajo sexto player for conjunto ensemble Los Donneños. In that more rural swath of South Texas, a music-obsessed folklorist like Strachwitz was a novelty.

“At that time, they had never met somebody like me,” he said. “It was always record people or businesspeople, and here comes this fanatic. Ramiro Cavazos introduced me to his wife, I’ll never forget, as ‘Chris, el fanático de música Norteña.’”

Through Cavazos, Strachwitz met Los Alegres de Teran, a group that supplies some of the film’s most haunting performances.

“For recording with one mic, it was the most gorgeously balanced acoustic music I’d ever encountered,” says Strachwitz.

In the valley, Strachwitz also met Narciso Martínez, “El Huracán del Valle,” considered the father of conjunto. In the early 20th century, Martínez learned accordion from Czech and German families living near the town of Bishop, 40 miles from Corpus Christi, and in 1935 teamed with bajo sexto player Santiago Almeida.

That collaboration established the accordion and bajo sexto as the core of the fledgling conjunto style. Martínez was honored in 1983 with a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, the nation’s highest honor in folk and traditional art.

One particularly memorable scene in Chulas Fronteras shows Martínez working his day job at the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville and feeding the elephants and toucans.

‘The Meadowlark of the Border’

Martínez wasn’t the only legendary originator captured in the film. Lydia Mendoza, called “La Alondra de la Frontera” (“The Meadowlark of the Border”), provides a compelling gravitas and welcome feminine presence in Chulas Fronteras.

“She’s the only woman they focused on in the film, which makes her role all the more important,” scholar Tejeda said. “Most of the time, it’s about men. Across cultures, music has been more of a macho, patriarchal business, but there’s always been women, they just haven’t gotten their due. That’s why it’s important that Lydia was in here. She’s one of the greats.”

After a recording session by the Mendoza family for Okeh Records in a downtown San Antonio hotel, Lydia became a musical star at age 12. A later session went down in the Acuña furniture shop — explained because furniture makers were among the sellers of early phonographs.

Eventually, Mendoza struck out on her own, signing with Bluebird Records, and becoming the star of the family with her famous solo version of “Mal Hombre.” She designed and sewed her own stage clothes and played to massive crowds across the U.S., Canada and Latin America. Thanks to her forceful guitar work and emotion-wrenched vocal approach, her classic 1934 recording “Mal Hombre” still sends shivers down the spine.

“Lydia sang in the vernacular, the peoples’ way of singing, not the highly trained or theatrical performers,” Strachwitz said.

The film takes the viewer inside Mendoza’s home, showing her making tamales by hand, singing at a wedding and describing her process.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s a corrido, a waltz, a bolero, a polka or whatever,” Mendoza said on camera. “When I sing that song, I live that song.”

Ultimately, Mendoza was honored with the National Medal of Arts, the Texas Cultural Trust’s Texas Medal of Arts, a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and even performed at Jimmy Carter’s 1977 inauguration.

“When I think of Lydia, I think of somebody like Leadbelly,” Texas State’s Hector Saldaña said. “Like a rock, just so singular. She was playing for the poorest of the poor ... and she was poor herself. Though she’s an icon and superstar today — in the relative sense — she wasn’t celebrated in her day. She was playing worker camps, in the plaza, on the streets. Her music was the people’s music. When she emerged, Texas was largely agricultural and poor.”

Only after her rediscovery in the 1960s was the singer celebrated and given the recognition she deserved, Saldaña said.

“The film is part of the reassessment. It’s way past her heyday,” he said. “The film shows her rediscovery.”

Soy Chicano

One of Chulas Fronteras’ most significant cultural contributions was that it didn’t just capture the originators of conjunto, it also showed a new generation picking up the mantle.

“It was the era of the Chicano,” Strachwitz said. The term ‘Chicano’ had previously been used with disdain — somebody destitute and uneducated — but, by the late ’60s, a new generation of Mexican Americans, tired of apologizing for their skin color and their culture, embraced the term.

In the film, Rumel Fuentes gives voice to the Chicano movement with a particularly rousing performance of the song “Soy Chicano.”

“Chicano, soy Chicano / ’Cause I’m brown and I’m proud / And I’ll make it in my own way,” he sings.

“The new Mexican Americans were proud of being Chicanos,” Strachwitz said. “There was a pride there. And that became a pretty popular song for Rumel and for Los Pingüinos del Norte, another group from the film.”

Fuentes’ youthful exuberance provides a compelling counterpoint to the film’s older generation. The bandleader had emerged from the civil rights and rock ’n’ roll era, making him a new type of performer.

“My God, you talk about a Bob Dylan type character, who had the balls to say it, to say what needed to be said,” Texas State’s Saldaña said. “When he’s expressing that stuff, there was a line drawn. Not all Mexican Americans wanted to be called Chicanos. In fact, many did not. ‘Chicano’ was more of a radical term and more confrontational. ... But, at the end of the day, Fuentes was right! He tapped into something, and you had to say, ‘Wow! .... This is us!”

Arhoolie recently released a posthumous collection of Fuentes’ songs from the ’70s, Corridos of the Chicano Movement.

Chulas Fronteras’ unflinching depiction of the Chicano movement, as well as the racism and police brutality faced by brown people, also impressed Palo Alto professor Tejeda when he saw the film as a youth.

“Be proud of who you are. That’s what Rumel said to us,” Tejeda said. “A lot of films wouldn’t get so politically involved. It captured the way it was, not only for our roots music, but for our young people in the Chicano movement. We were demanding our rights, learning our roots and our cultural identity, learning to take pride in who we are, when society would humiliate us as brown people and poor people. It’s the struggle of the indigenous, and it’s been happening for 500 years.”

That struggle finds musical form in Chula Fronteras’ opening scene, where Ramiro Cavazos sings the classic “Canción Mixteca” accompanied by footage of a ferry crossing the Rio Grande.

“It’s interesting that song is called ‘mixtec,’ which means indigenous,” Tejeda said. “It’s a beautiful lament [about] the people who had to leave on the migrant trail to survive. Like this whole border culture, it’s a fusion — an indigenous song played on a European instrument and sung in Spanish.”

Hidden history

While music may be the primary draw for modern viewers looking to explore Chulas Fronteras, it wasn’t the only thing that drew Strachwitz to make the film. He was also motivated by his desire to share a hidden history.

“I had always enjoyed history in school, but it was usually taught from the perspective of the ruling classes and their culture,” he wrote in the liner notes for 2000’s The Journey of Chris Strachwitz boxset. “Suddenly, as a record producer, I found myself face to face with other social strata, whose music, culture and history no one seemed to have charted.”

As an immigrant and an outsider himself, Strachwitz sympathized with those on the margins.

In the 1990s, following a lifetime of hunting down the most unique and fantastic regional music in America, Strachwitz made arguably his greatest and most lasting contribution to Mexican American Culture — the Strachwitz Frontera Collection at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC).

Founded in collaboration with Guillermo Hernández, a UCLA Spanish professor who was one of the foremost authorities on the corrido and was later the CSRC’s Director, Frontera maintains the largest repository of commercially produced Mexican and Mexican American vernacular recordings. Its more than 160,000 individual recordings, many rare or impossible to find, are available free online at frontera.library.ucla.edu and at youtube.com/c/FronteraCollection.

Getting the archive off the ground required an infusion of capital, and Strachwitz turned to musicians for help with that. After bringing Grammy-winning Norteño group Los Tigres del Norte to California for a folk festival, Strachwitz played the group some of his original 78 rpm recordings of early 20th-century corridos.

“They were amazed that these songs they play were recorded way back then,” he said. “They thought it was just an oral tradition! But we had the records!”

Jorge Hernández, Los Tigres’ leader, realized the importance of the recordings and the group donated $500,000 to jumpstart the Frontera collection.

“[Strachwitz’s] life work documenting the history of Mexican American music marks one of the great social and artistic contributions to U.S. pop culture of the 20th century,” wrote Los Angeles Times journalist Agustín Gurza, editor of the Arhoolie Foundation’s UCLA Frontera Collection.

Besides giving the recordings a home in perpetuity where they can inspire future generations of musicians, historians and culture buffs, the project gives artistic legitimacy to corridos, Strachwitz said.

“UCLA believed that these corridos were the literature of the people that they cater to,” he added. “By doing an academic study of these corridos, it legitimized it as literature of the common man.”

Corrido legacy

After the completion of Chulas Fronteras, Strachwitz returned to San Antonio for a shorter follow-up film, Del Mero Corazón. Released in 1979, Del Mero Corazón focuses less on corridos and more on the love songs of the border. Later trips to South Texas found Strachwitz researching the narcorrido movement, including a visit to the hideout compound of legendary narco Pablo Acosta and his girlfriend Mimi Webb Miller, whose whirlwind romance was depicted on the current Netflix series Narcos.

“She was a real character,” Strachwitz said. “That was a bit scary, that trip. But fascinating.”

Recalling the magic captured in Chulas Fronteras, Strachwitz concedes that the film likely documented what was just a brief window in time for South Texas’ indigenous music.

“You’ll never repeat that music the way it was then,” he said. “But the lives of the people it shows ... haven’t really changed that much.”

To that end, Strachwitz brushes off the “roots” tag often used to describe the music he documents.

“I don’t want to call it ‘roots music,’ because ‘roots’ indicates being stationary,” he said. “I think of all music as rivulets that run into a river and a river that runs into something else. Everything is moving constantly, and one rivulet brings one influence, another rivulet brings another influence.”

Conjunto scholar Tejeda has a similar view.

“The songs document this history that we’re still living through, and that’s the importance of the arts, of music, of literature: it documents our culture,” Tejeda said. “This is who we are. And we are proud of it. This film gave us that pride. Because there’s still not that much in film form that depicts our culture — as Tejanos, as Chicanos, as Texas Mexicans, as border crossers.”

He added: “And that is what makes this film so much more important. There are so many great stories yet to be told. We just keep working for a better future for our kids. That’s where our liberation lies. And I hope the music shows the joy of that struggle for liberation.”

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.