A Hill Country woman helps 25 Sri Lankan families rebuild their homes and their lives

Epiphanies happen in the most ordinary moments. For Becky Westbrook, it happened to be while she was watching television.

On December 31, 2004, Westbrook, a horse breeder, came in from her Hill Country ranch to get lunch, and switched on Fox News, as she always does. Correspondent Jennifer Griffin was covering New Year’s Eve in Southeast Asia. Six days earlier, a Magnitude 9 earthquake had ruptured the sea floor just off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. In the resulting tsunami, 33-foot waves swelled across the Indian Ocean at 500 miles per hour, destroying villages and killing more than 225,000 people in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, South India, and Thailand.

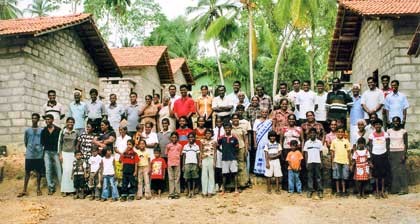

| The villagers of Lassanagama, founded on October 20, 2005, on the southwestern side of Sri Lanka. These 25 families once inhabited the coastal town of Totagamuwa, which was destroyed by the 2004 tsunami. (Photos courtesy of Becky Westbrook) |

Westbrook doesn’t remember from where Griffin was broadcasting, only that as Griffin described the people lighting candles to welcome in the new year the reporter broke down emotionally. “She lost every bit of professionalism and allowed a little bit of humaness to show through,” says Westbrook, “and when she did, it became very real to me. I realized that I had to do something.”

Two months later, Westbrook went to Sri Lanka, where, with the help of a non-governmental organization and $120,000 of her own money she bought two acres of land on an old cinnamon farm and two concrete block machines, and built a village on the southwestern side of the island, providing homes for 25 families whose village had been destroyed by the tsunami.

Westbrook’s Boerne home is modest by some standards: A light-filled central living area with a small kitchen, and one large bedroom at each end of the building. From her limestone patio there’s nothing to see but the sunlight filtering through the oaks, and only the shrieks of her cockatoo to break up the quiet.

On the wall of her spare bedroom there’s a photo of Westbrook riding in a cutting competition labeled “Rookie of the Year 2001.” In it, the horse she’s riding is nearly parallel to the ground, but her expression is dead calm and her tall, white cowboy hat is square; she could be sideways on a horse, or she could be waiting for a bus.

Yet, when Westbrook describes her first trip to Sri Lanka, she talks about fear. “I’d never been to a Third World country,” she explains in a stream of words. “You are dodging people, tuk-tuks, goats, there’s four different faiths there, and poverty like I’ve never seen.

“In the north country, where the Tigers are still fighting, they have checkpoints and there’s guns everywhere. What was it like for me? It broadened my world.”

In Colombo, Sri Lanka, Westbrook met with Basil Fonseka, former national director and South Asia coordinator for Habitat for Humanity and founder of Jana Tharana Padanama, a non-governmental organization that provides education, job training, and housing programs. Fonseka guided Westbrook on a tour of devastated areas, and introduced her to the various small NGOs doing tsunami relief work.

In her journal, Westbrook describes the destruction in Peraliya: buildings reduced to rubble; blue Tyvec tents with families of six packed into them, sweating in the 90-degree heat; and trees uprooted and dragged across the land, forming huge trenches filled with stagnant water and mosquitoes. It was in Peraliya that villagers, seeking refuge from the tsunami’s first wave, climbed onto a crowded commuter train, only to have the second wave sweep it off the tracks, killing all 1,500 people aboard. “I would see these huge black spots on the road,” says Westbrook, “and I would say, ‘What is that?’ ‘Well,’ Basil would say, ‘That’s where they had to pile up the bodies and burn them.’”

| Becky Westbrook, a Hill Country rancher, presents Ariyasiri Rajapaksa with a hearing aid (below). Rajapaksa is one of 101 Sri Lankans Westbrook relocated to Lassanagama, a beautiful village in Sinhalese. |

After almost three weeks of travel in Sri Lanka, Westbrook had eliminated all of the NGOs but Jana Tharana. “I was amazed at the crookedness of some of the NGOs,” she says. “Especially the orphanages — my God, children in squalor, grass 4-feet high. It was just a ruse to make money.”

Initially, Westbrook was interested in a school that had been destroyed in Totagamuwa, a small village near Hikkaduwa and Peraliya, on the southwestern coast. Fonseka thought they could rebuild the school for $40,000, but on the day they returned from traveling in the north they found the entire village celebrating: The Italian government had agreed to rebuild the school — for $500,000. “I thought, ‘These people had no money, they had lost their homes, jobs, businesses, and loved ones,’” Westbrook says. “And here the Italian government was buying them a half million dollar school. It didn’t make sense.”

While she was visiting the site, a 10-year-old girl wandered up and introduced herself as Primali. “She says, My house, no — tsunami. And I said, ‘Oh honey I’m sorry,’” explains Westbrook. “We walked along, ‘My school, no — tsunami’, and I said, oh I see. Then she looked at me, just expressionless, and said, ‘my father, no — tsunami.’”

Determined to help Primali, Westbrook gathered the women of the village, explaining that the government forbade anyone to build within 100 meters of the ocean, so she couldn’t build in Totagamuwa, but if she could find land, would they be willing to move?

The villagers no longer wanted to live near the ocean; they feared another tsunami would strike at night, and wash them away while they were sleeping. Fonseka and Westbrook formulated a plan: As the Los Encinos Foundation, named for her ranch, Westbrook would buy enough land and materials for 25 homes, and she would pay one skilled carpenter to oversee the project. Fonseka would coordinate building the village in Sri Lanka, acting as a translator and a counselor, and providing the plans for the houses.

Only Totagamuwa villagers could live in the new village, Westbrook would not allow drug use (two families were excluded because of this), and the villagers would have to build their own homes. “We met with the people and I explained the concept of sweat equity, using all those little clichés,” says Westbrook. “I’m not breeding entitlement, you will work for this house or you don’t get this house.”

Westbrook keeps a floppy red binder she calls the Village Book. In it are the Totagamuwa villagers’ memories, most told to Westbrook in broken English, of what happened to them when the tsunami hit Sri Lanka on the morning of December 25, 2004.

Jinartne, his wife, and their eldest daughter survived the first tsunami, but the second wave washed them into the top of a coconut tree; while Jinartne clung to the tree, his wife and daughter lost their grip and drowned. A wall in Samanpriya Wejetillake’s home collapsed. In the ensuing flood he held his mother in one hand, his 5-year-old son in the other. When his mother’s hand slipped, he couldn’t abandon his son to swim after her, and she washed away. Primali fled the tsunami with her older sister and little brother, but their father, on crutches, couldn’t run and was carried off by the second wave.

|

Sri Lanka Total fatalities: In Sri lanka, population 20 million: In the Galle District of Sri Lanka: Sources: World Health Organization, Task Force for Rebuilding the Nation |

The Village Book also records the family’s hobbies — Primali plays badminton and is an avid reader — how they make a living — doctors, seamstresses, fisherman, businessman — and what the children want to be when they grow up. “I began to learn these people, their stories,” Westbrook says. “But the beautiful part is, when we completed the village, I was able to say, we need 10 sewing machines, a boat, and a hearing aid.”

Westbrook’s direct involvement in the project has earned her the respect of volunteers who worked in the village. “A lot of people gave what they could,” says Sara Heard, a New York City teacher who spent her summer helping build houses in the village. “And Becky gave more, but what I admire her for is doing it in a humane and personal way, and taking charge and seeing that her money changed lives, instead of handing it to someone else.”

For her own part, Heard believes that her physical presence carried more weight than the bricks she hauled. “I went naively thinking that they needed my labor; well, I’m not a skilled carpenter, so my labor is really not that important,” she says. “The fact that an unskilled American showed up every day, got sweaty and dirty, and learned their names, had a greater impact.”

Not all volunteers were as mellow. Although Westbrook is loath to say that building the village was a challenge, she admits there were clashes between volunteers — who showed up in large numbers from around the world — and Sri Lankans over construction.

Shawn Bonner, a friend of Westbrook’s who visited the village, says well-meaning volunteers believed the locals took too many breaks — tea at 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. in addition to lunch — and worried about the efficiency of building methods. Inevitably, a volunteer would present his or her way as “the only way” and “what Becky would want,” creating discord with the villagers.

“Basil handled the Americans, and I handled the business, we had our roles,” says Westbrook, explaining that she didn’t mediate those conflicts. “But my impression was that most people had a positive experience.”

Warren Borror, a San Antonio volunteer who worked on the village pre-school for almost two weeks last month, says the monsoon season hampered his work, but he still felt like the trip was a success. “I feel like one of the greatest accomplishments was being accepted by these people, whose perception of me is that I make so much more money than they do.”

In Sri Lanka, says Borror, days unfolded in a series of social interactions. Each day, a different family in the village hosted the workers, providing black tea and a sweet, such as shortbread. Women and children visited the workers during the day, and large meals were prepared together in the evening, on the floor of the kitchen or living room.

In the afternoons people gathered at the well in their sarongs, either as a family or in groups of men or women, to bathe. “Sometimes the families would take a 30- or 40-minute bath together,” Borror says. “Can you imagine? It was just really sweet.”

| Although Westbrook bought the land and provided the building materials, the villagers built and decorated their own homes. |

If there were challenges during construction, they had more to do with materials than conflicting work ethics: Sri Lankan workers sift and mix cement by hand, for example, and reuse materials until they can’t be used. “That’s where I’d get frustrated,” Borror says, “You’re not even using a piece of lumber, you are using shards of wood; you hit it and it splits apart — but they’re doing it and not even batting an eye, so you feel like a big whiner for asking for new wood.”

In the end, he adds, “you have to say, ‘I’m here to help them, and so it’s by their method I’m doing it.’ They were patient with me.”

Even without power tools, the village was completed in five months, with the exception of the pre-school, which opens at the end of January. Room to Read funded the school and is providing books, uniforms, furniture, a playground, and a teacher for one year.

On October 20, the villagers officially celebrated the completion of the village, which they named Lassanagama, beautiful village in Sinhalese. At the ceremony, Westbrook presented the families with the keys and deeds to their homes. The houses belong to the children of the village, but they may not sell or rent them.

The houses are 500 square feet a piece, with two doors, four windows, and either three or four rooms. Westbrook built two wells on the property, for drinking and cooking water, which are hooked up to spigots around the village; for some families, this is the first time they will have running water. Although Westbrook plastered the walls and exterior of each house, it’s up to the villagers to decorate and paint their own homes.

In addition, Westbrook and Fonseka gave the villagers 26 bicycles, a gift from the Dutch Reform Church, and 10 sewing machines, a boat and engine, and a hearing aid that were also donated by NGOs.

Westbrook predicts that Lassanagama will be thriving in five years, if for no other reason than that the villagers all know one another. “My concept is really a prototype. Other people are building houses and giving them to groups of strangers,” she says. “What I did was to move a village. It’s like a family: They will work on one another’s houses because I’ve told them they must.”

In a letter from Lassanagama, one of the villagers writes to Westbrook, “thank you for the sewing machine Now we earn our living by sewing dresses and 100 mosquito nets Furthermore, we sleep in our new house at Lassanagama without fear of Tsunami.”

The villagers view Westbrook as a respected member of the family, not a mother, but perhaps a larger-than-life grandmother. Before volunteering in Sri Lanka, Heard had never talked to Westbrook, a fact the people of Lassangama found unbelievable, “They would say, Friend of Becky, Friend of Becky,” says Heard, “I would try to explain that Texas and New York are very far apart, but they couldn’t accept that I didn’t know her, they would try to trick me by periodically asking, ‘What news of Becky?’”

Today, Westbrook is working on another village. In July, she attended a Fort Worth horse show where she encountered an old friend, Glade Knight. “I told him that I could build a village for what it cost to buy a good cutting horse,” she says, “and he said, ‘Let’s do it’.”

The new village will be completed in July, and will relocate 60 families to 2-and-a-1/2 acres. Room to Read has already committed to building another school. “Sometimes I think I should make Glade do the work on this next village, so he can get in there and work with those people,” she says, “To think that I was just going to write a check — how much would I have missed if I had stayed detached?” •

By Susan Pagani