In his keynote to the Democratic National Convention in September, Mayor Julián Castro spoke of his grandmother, an orphaned immigrant from Mexico, who cleaned houses, cooked, and babysat to raise her family. “My grandmother never owned a house,” Castro said. “She cleaned other people's houses so she could afford to rent her own.”

The story of Castro's grandmother is part of the fabric and history of San Antonio's working class, says Genaro Rendon, director of the local nonprofit Southwest Workers Union. “That story is San Antonio, it's what thousands of workers here have done to provide for their families, to give them better opportunities,” Rendon said.

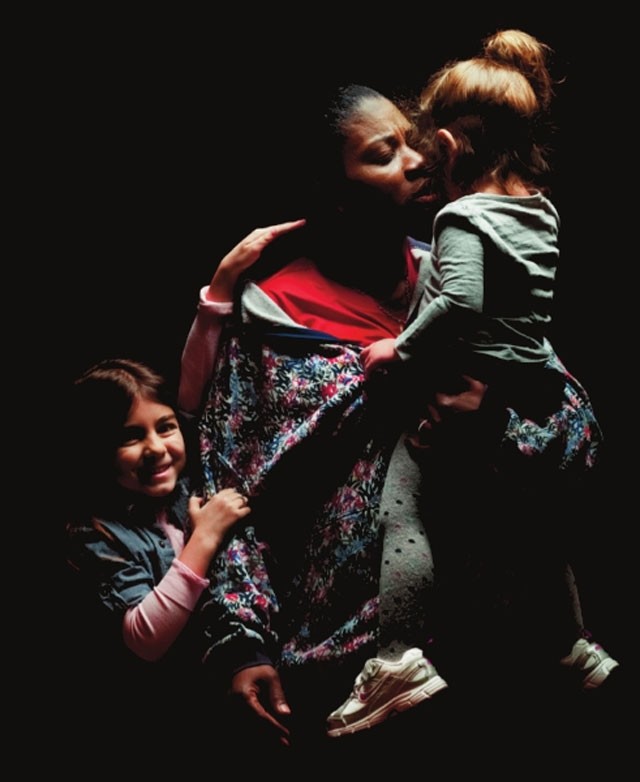

In 2010 SWU launched its local effort to organize domestic workers, hosting monthly meetings educating workers about their rights. This year SWU helped locate and interview over 150 local domestic workers as part of a first-of-its-kind national survey looking at pay and treatment of domestic workers. The report, released last week, says the workers often overworked, underpaid, abused, and excluded from protections that regulate other professions.

The report, from the National Domestic Workers Alliance, spelled out findings from interviews with over 2,000 housekeepers, nannies, and caregivers across the nation. According to the survey, workers, the vast majority of whom are women of color, face seriously low pay, with 23 percent paid below minimum wage in their respective states. Nearly half surveyed weren't paid enough to support a family, and 10 percent were paid below what employers had originally agreed to. Some 20 percent said there were times within the past month when they couldn't afford food.

Only 4 percent of domestic workers surveyed for the report received health care from an employer. While some managed to buy coverage on their own, 65 percent worked without any health insurance at all. Many told stories of being fired after getting sick, injured, or even pregnant, said report co-author professor Nik Theodore of University of Illinois at Chicago. Some spoke of verbal, physical, or even sexual abuse at the hands of employers or their families, according to Theodore.

The roots of unequal protection and mistreatment go back to the 1930s, Theodore says, when domestic and farm workers were left out of federal fair labor protections. “That started a pattern of what has been historic exclusion from employment and labor laws that most U.S. workers take for granted,” he said. “The vulnerabilities for these workers lie at the intersection of race and immigration status, gender, and the ways in which we've viewed women's work for far too long in this country.”

Emilia, a local undocumented immigrant, says she's worked in and out of North Side homes cooking, cleaning, and providing childcare for the past two decades. “When the holidays came around, it was always double the work, double the time,” she said. “Still, I never got paid more.” Recently at a local dentist's office, Emilia says she cleaned and did groundskeeping work, often working from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. She was paid just $100 a week.

Organizing with SWU and the local group Domestic Workers in Action, Emilia said, “We're just trying to say we're humans, too. We just want to be paid for what we work.”

According to the national report, 91 percent of domestic workers surveyed faced problems in the workplace but didn't complain out of fear of losing their jobs. For those who lost their jobs, 23 percent said they were fired for protesting poor workplace conditions, while another 18 percent were fired for contesting a contract or agreement their employer failed to live up to. Around 85 percent of undocumented workers said they quietly endured poor conditions, or low pay, or even abuse because they feared their immigration status would be used against them.

Groups like SWU and the National Domestic Workers Alliance hope to push local, state and federal legislative reforms to offer domestic workers the same protections afforded professions. They're also encouraging workers to draft written contracts with employers – though the national survey showed employers often considered those agreements non-binding when challenged.

While SWU's Rendon sees little chance for moment on the issue at the Texas Legislature in the near future, he looks to New York City, which in 2010 passed a domestic workers bill of rights. Rendon says local organizers plan to push for San Antonio City Council to consider something similar this year.