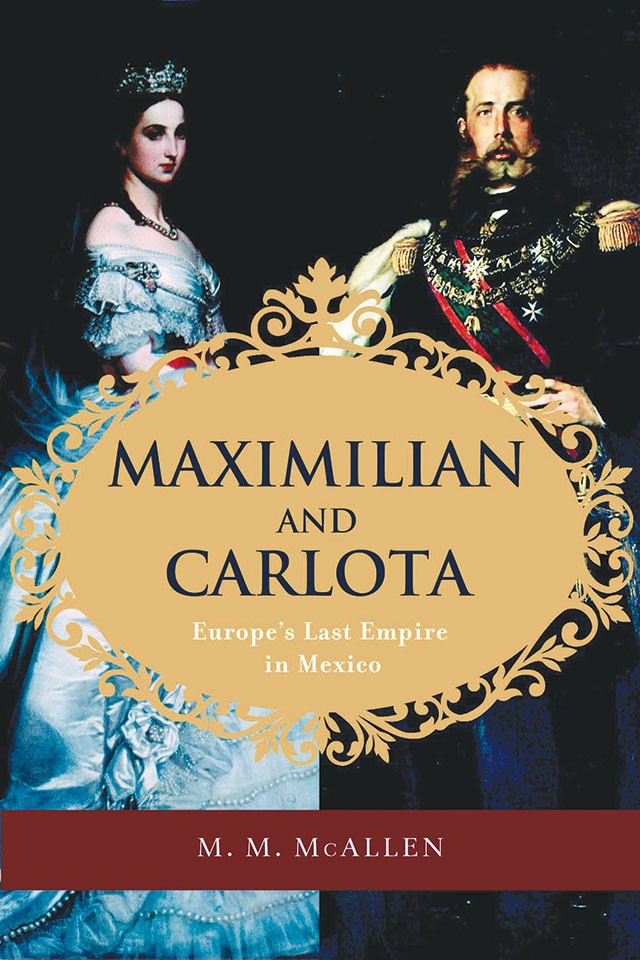

This month marks the 150th anniversary of the last attempt at European rule in Mexico. Local historian M. M. McAllen brings this fascinating story to life in her new book, Maximilian and Carlota.

It goes a little something like this: French Emperor Napoleon III, nephew of Bonaparte, sees an opening in the unsteady beginnings of Benito Juárez’s emerging Mexican democracy and puts the might and weight of Europe’s intertwined royal families into establishing a new empire there. He recruits young Maximilian von Hapsburg, second son of the Austrian royal family, and his wife, the Belgian princess Carlota, as the emperor and empress of Mexico, with tragic results.

Although full of detailed military and political intrigue, what sets this history apart is McAllen’s intimate portrayal of the young rulers. Especially sympathetic is Maximilian, an idealist always in the competitive shadow of his older brother, Franz Josef, emperor of Austria for his entire adult life.

Maximilian does not take Napoleon’s offer lightly. He repeatedly insists that the Mexican people must vote to show their desire to have him as their ruler. Establishing a monarchy through a democratic process may seem unusual, Maximilian’s insistence that as many of the Mexican people as possible be polled, not only the wealthy or the clergy, was even more novel. He endures additional sacrifices to accept the rule–including Franz Josef’s requirement that if he take up the throne of Mexico, Maximilian renounce all claim to any titles or right of succession in Austria.

Maximilian and Carlota begin their reign with a real desire to improve the lives of the Mexican people, attempting numerous and ambitious reforms. They build new public squares resembling European city centers, construct new roads, modernize the currency, rebuild the national portrait gallery to honor Mexico’s past (and, of course, present) rulers, preserve historic artifacts and “[deploy] scientists to study all matter of Mexican plant life, geography and mapmaking, agronomy, history, archaeology and medical sciences.” Carlota focuses her efforts on the poor, establishing charities to raise money for hospitals and schools. The couple invites leaders of the indigenous tribes, like the Kickapoo Indians, to court. After the first year, Maximilian feels the new, modern nation he aspires to rule is starting to come together. He rejects the European mentality that the Americas, and especially Mexico, are backwards and inferior, instead reveling in his new culture.

And yet, the country continues to be engulfed by violence. Juárez and the Republican militia continue to gain ground while the Catholic Church leadership refuses to fully back Maximilian, bent on their own need for more power and control of the country. Napoleon keeps hedging his bets in the United States Civil War, making lasting alliances with either the Union or the Confederacy impossible. European troops and money dwindle, leaving Maximilian’s supporters increasingly unsupported. Maximilian suffers from a string of sicknesses, including dysentery, prompting Carlota to step forward in his stead on several occasions. Although intelligent and ambitious, a woman ruler is not well received. The new monarchy is falling apart. In 1866, Napoleon abandons the project, withdrawing the last of Europe’s troops.

Brokenhearted, Maximilian considers abdication, but is urged by Carlota to stay and fight for what they have begun. Despite their decision to persevere without France, all that results is a difficult and protracted denouement. Carlota becomes mentally unstable, increasingly paranoid that she will be assassinated or poisoned. Her madness does not endear her to the European powers, including the Pope, whom she calls on for help. Maximilian returns to the military front, but he and his generals are captured by Juárez. Although personal escape is possible, he refuses to leave his men behind and is executed by firing squad.

McAllen notes that although Maximilian and Carlota had the best of intentions towards their adopted homeland, what they “did not anticipate was that the Mexican nation no longer remained open to discourse about its future or to interference by foreign countries … A modern Mexico had arrived.”

Young, naive and optimistic upon arrival, but broken and rejected in the end, I would still argue that Maximilian and Carlota rose above their roles as political pawns for Europe, in a small way succeeding in the “experiment” that was their moment in Mexican history.

Maximilian and Carlota: Europe’s Last Empire in Mexico

By M. M. McAllen Trinity University Press | $29.95 | 552 pp