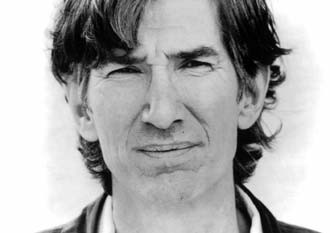

When Townes Van Zandt died of a heart attack in New York City at age 52, it seemed like one more nail in the coffin for the American songwriter. Sure, we still have Dylan, but he gets

Van Zandt expressed the confused emotions of his generation with the true voice of a poet, and the finger-picking of a good ol' boy. He effortlessly bridged the gap between the folkies and the hippies, his voice rising up from the Houston wards to speak the name of feelings that had just begun to be felt at the end of the '60s. The four earliest albums in the series - For the Sake of the Song, Our Mother the Mountain, Townes

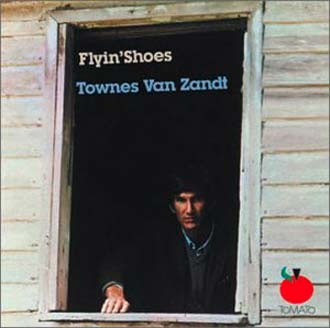

Van Zandt, and Delta Momma Blues - represent an intense handful of years in the artist's life, a time of incredible prolificity and influence in songwriting circles, when one illuminatory record seemed to follow another in a string of inspired writing and recording. From deep folk to the walking blues to the white man's honky-tonk, Van Zandt summoned the musical forces of the time to create something free and new. During these years, his music took shape as a force to be reckoned with, and it never lost that freedom. On the fifth reissue of the series, Flyin' Shoes, Van Zandt experimented with a sound that alienated many fans at the time, but rings true in hindsight. (To draw an unexpected analogy, this is his Electric Mud album - critically panned but great on its own). The last album Van Zandt cut before he died, 1993's The Nashville Sessions, allowed him to rework some older songs and bolster the bare

Yet for all the songs Van Zandt shared with the world, his music also expressed a sad personal journey, a constant need to escape the emotional demons that haunted him. As Jimmie Dale Gilmore says in the new liner notes to Our Mother the Mountain, "In his songs, Townes is usually talking about the consciousness and the primal, universal battle of darkness and light. Townes was so articulate about it, he was so passionately feeling that he spent a whole lot of energy trying to escape the intensity of his feelings." The energy he spent was physical as well as creative, and he took more than musical cues from his forebear, Woody Guthrie. A consumate rambler, Van Zandt traveled the country, constantly floating between Texas and the Colorado Rockies with a notebook full of poems (songs in progress) and little

Despite the music's success and all the running, Van Zandt never fully outran himself. It comes through in the songs: Van Zandt could make a love song sound incredibly sad, and I sometimes think he might have mixed up the lyrics and the music, recording a funeral dirge where he should have recorded a ballad. Of course, there were always tensions throughout his life, starting from when he eschewed his prominent Texas oil family's gilded roots for the life of a roving troubador. Then came alcoholism, and a number of other obstacles that prevented him from taking his place among the pantheon of well-known (and better paid) songwriters. By the time he died, he should have been taking it easy as a star in his own right. Instead, as a friend remarked, "He had it all, but he always had the blues."

As painful as this constant uneasiness must have been for Townes, perhaps it was a blessing in disguise for the rest of us. Among the 70 or so songs Van Zandt left the world, there are innumerable hard truths about life resting like glowing pearls within the lyrics. "Sometimes I don't know where this dirty road is taking me," he sings on "Waitin' Around to Die" (For the Sake of the Song), "Sometimes I don't even see the reason why/I guess I keep on gamblin', lots of booze and lots of ramblin'/It's easier than just a-waitin' 'round to die." •