But, in reality, the San Antonio area is ground zero for Trump’s zero-tolerance policies.

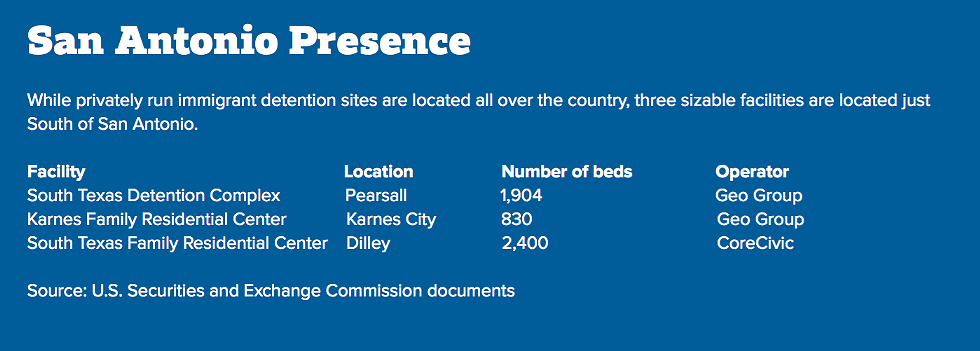

That’s because three of the largest federal immigrant detention centers are located in small towns an hour or less south of the Alamo City. And they’re all run by private prison companies whose treatment of inmates has been decried by human rights groups.

A 2,400-bed detention center in Dilley operated by CoreCivic Inc. and an 830-bed facility in Karnes City run by Geo Group Inc. represent 95 percent of Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s capacity for detaining migrant families. A third, higher-security detention site — Geo’s 1,900-bed jail in Pearsall — houses detainees awaiting immigration hearings, some jailed for nothing more than minor traffic violations.

ICE is spending $2 billion this year to hold immigrants at privately run jails like the three south of San Antonio, and it wants five more around the country, according to federal documents. Boca Raton, Fla.-based Geo and Nashville-based CoreCivic — two of the nation’s largest private prison companies — will likely benefit from that expansion, observers say.

“People should be asking why we’re spending so much tax money to have private companies lock up people who aren’t dangerous,” said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, a senior fellow at the NYU School of Law’s Brennan Center who follows the private-prison industry. “Our country has a history of stoking unfounded fears around immigration and crime.”

To be sure, groups like the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Human Rights Watch and Detention Watch Network have assembled detailed reports of medical neglect, sexual assaults and deaths of migrants in private custody. Those result, advocates argue, as corporate jailers cut corners on caring for detainees so they can attain higher profits.

Such concerns came into sharp focus this month when human rights groups demanded that 16 infants under a year old be released from the Dilley detention center, citing lack of medical care, baby food and clean water. The babies were released after the story made national news.

Responding to an interview request for this story, CoreCivic sent an email saying its Dilley site represents a “safe and appropriate” environment for families. In addition to recreational facilities, a library and chapels, it offers Pre-K through 12th-grade educational programs, the company added.

Similarly, Geo provided an email statement ticking off resources available at its Karnes City facility — among those, educational programs, 24-hour medical care and a range of recreational activities.

“The company’s employees are proud of our record in managing ICE Processing Centers with high-quality, culturally responsive services in safe and humane environments,” the Geo statement reads.

For its part, ICE issued an email statement saying allegations of unsafe conditions at Texas detention centers are “utterly false.”

The Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general issued a 2017 report calling family detention sites “clean, well-organized and efficiently run,” the agency added.

With its razor-wire fences and windowless concrete walls, Geo’s Pearsall site resembles a high-security prison. As such, it’s emblematic of the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy, which aims to use detention as a deterrent to asylum seekers.

And, according to immigrant rights groups, the conditions inside are no picnic.

Work at the lockup isn’t mandatory, but advocates say it may as well be. It’s one of the few releases from boredom and the only way many of the detainees are able to make money to spend at the commissary. Those lucky enough to pull kitchen duty make $3 a day, while those sweeping floors and doing other menial work make just $1 a day.

Geo manages its end-run around minimum wage law because ICE considers those who do labor “volunteers” instead of employees. The availability of those volunteers, critics argue, allows the company to hold down its own labor costs and add to the bottom line.

“I don’t see any excuse for a corporation to make a profit off of someone’s indentured servitude,” said Sara Ramey, executive director for the San Antonio-based Migrant Center for Human Rights and an attorney who represents clients held in the jail.

Washington State also has concerns with the practice. Its attorney general sued Geo last year for using that pay scale at its Tacoma facility, arguing that the company is violating state minimum wage laws.

In its email statement, Geo defended the practice, saying its pay rate was set by ICE and the company is “required to abide by these federally mandated standards.”

But low wages aren’t the only problem human rights groups have with the private detention centers south of San Antonio.

Geo’s Pearsall site was cited in a recent Human Rights Watch study that documents the high number of recent deaths at ICE detention facilities. And, in 2014, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund submitted a complaint over allegations of ongoing sexual abuse of women detained in the Karnes City center.

In Dilley, an ICE contractor provides medical care, but is unable to provide on-site specialists, such as cardiologists or obstetrician-gynecologists, advocates said. What’s more, many of the detained children, already traumatized by the conditions that led their families to flee their home countries, are unable to cope with weeks or months of detention as they wait for their asylum cases to play out.

“We have serious concerns about the mental and physical effect detention has on these children,” said Katy Murdza, advocacy coordinator with the Dilley Pro Bono Project, which provides legal help at the site. “We see behavioral regression — children wetting their beds, insisting on being carried by their mothers, even though they can walk on their own. We see them refusing to leave their mothers’ side.”

Prison companies such as Geo and CoreCivic bill the government up to several hundred dollars a day per inmate in their custody, according to human rights groups. That makes warehousing migrants a big business.

Last year, Geo turned a tidy $144.8 million profit on revenues of $2.33 billion. For its part, Core Civic reported earnings of $159.2 million on revenues of $1.84 billion.

And those corporate gains are likely to grow as the Trump administration continues its crackdown, observers say. Federal data obtained by the New York Times shows that in September of last year, 12,800 migrant children were in federally contracted shelters — a five-fold jump from a year prior.

“The costs to continue warehousing people are astronomical,” said U.S. Rep. Joaquin Castro, a San Antonio Democrat. “For the cost we’re paying per day, you could put them up in a Ritz-Carlton pretty much anywhere in the world.”

But Castro, who chairs the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, said his concerns go beyond the waste of tax dollars. His recent tours of detention facilities in Texas, New Mexico and Florida have convinced him the current system is “morally bankrupt.”

“In addition to the problematic profit motives, the use of these private contractors creates a system of less transparency and less accountability,” he said.

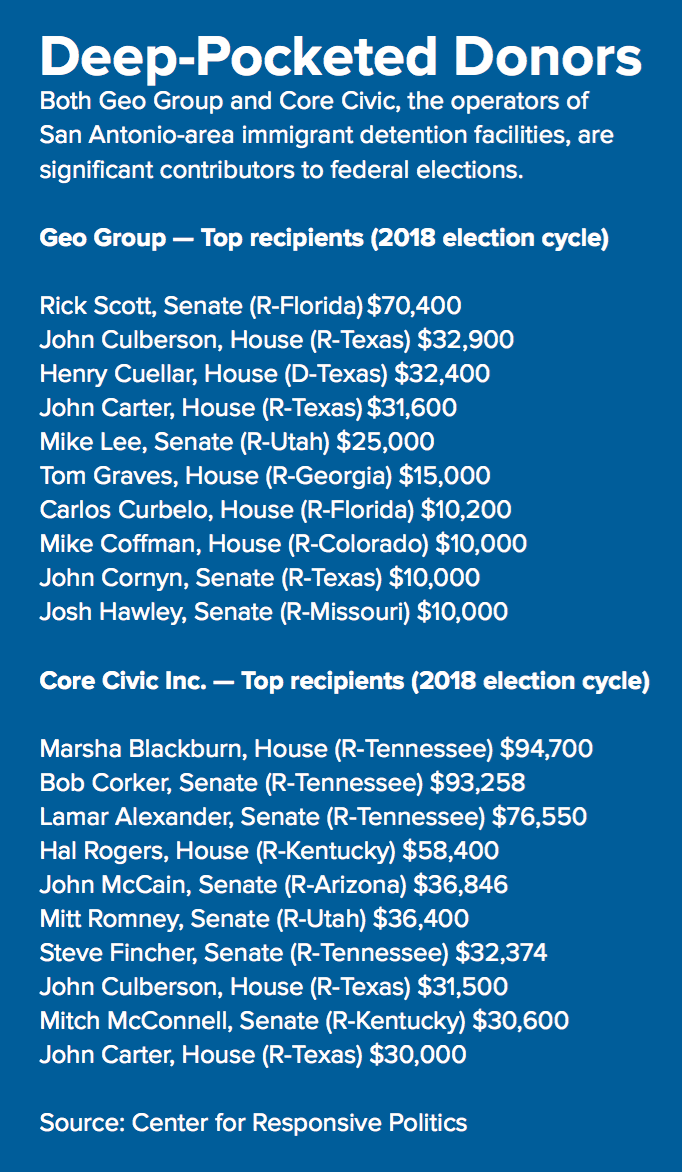

Castro is among a growing number of lawmakers advocating for more scrutiny for private detention facilities. However, Geo and CoreCivic have spent freely to make sure they have Washington allies, mostly on the Republican side of the aisle.

Last year, Geo reported nearly $1.6 million in federal lobbying expenditures, while CoreCivic reported $1.2 million, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics.

In the last election cycle, Geo also flowed $1.3 million to federal candidates, including San Antonio Congressman Henry Cuellar, a Democrat, and Republican Texas Sen. John Cornyn. CoreCivic funneled more than $378,000 to federal campaigns during the cycle.

What’s more, the companies’ expenditures suggest they see an ally in Trump. Geo gave $250,000 to fund the president’s inauguration ceremony, according to CRP’s data. Meanwhile, a subsidiary of CoreCivic ponied up an equal sum for the festivities.

“These companies have an incentive to keep costs down and to keep beds filled,” said Kathrine Russell, a staff attorney with San Antonio-based immigrant legal services provider RAICES, which represents clients at the San Antonio-area detention sites. “There’s a real concern the companies are lobbying for more people to be detained and for detentions to last longer.”

The predictable response from immigration hardliners is that if people don’t like being locked up like criminals, they shouldn’t cross the border illegally.

But immigrant rights groups argue that the punishment doesn’t match the crime. Being in the U.S. without papers is a misdemeanor offense. Not to mention, immigration detention is technically a civil, not criminal, matter.

Why then, advocates ask, are detention facilities being run like prisons for hardened criminals? And since most of the detainees don’t represent flight risks as they await immigration hearings, why aren’t they being released on their own personal recognizance or with an ankle monitor?

The Obama administration’s Justice Department in 2016 determined that private prisons were more violent that government-run facilities and began phasing them out. However, Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, reversed the order after taking office.

And with Trump’s turbocharged approach to immigration enforcement, it looks likely his administration will only increase its reliance on private detention.

At present, there are 829,000 cases pending in U.S. immigration courts, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, which tracks federal spending. That backlog has increased by 50 percent since Trump took office in 2017.

Last month, 86 U.S. reps sent a letter to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Director L. Francis Cissna demanding an explanation for the delays and voicing concern over the “adverse effect on American families, U.S. businesses and vulnerable populations.”

While there have been baby steps such as the recent hiring of 50 new immigration judges, the backlog doesn’t appear to be clearing up any time soon. In the meantime, the Trump administration seems sure to continue its reliance on private detention sites like the three south of San Antonio.

“What makes it troubling is that these detainees haven’t been convicted of anything,” said the Brennan Center’s Eisen. “All they’ve done is cross the border seeking asylum.”

Stay on top of San Antonio news and views. Sign up for our Weekly Headlines Newsletter.