Contemporary Artists Help Redefine the ‘Icons & Symbols of the Borderland’

By Dan R. Goddard on Wed, Oct 11, 2017 at 12:00 pm

Looking like he just stepped out of a Terminator movie, a cosmic knight wearing futuristic armor and holding a high-tech rifle like a medieval lance, the U.S. border patrol agent in El Paso artist Antonio Castro’s El Nuevo Coloso (The New Colossus) reigns supreme over the familiar-looking, long-haired, bearded, emaciated prisoner wearing a loin cloth and kneeling on the banks of a river in The Terrorist’s Weapons, merely the tools of a carpenter.

Castro, a graphic designer and children’s book illustrator, may be a tad romantic and his richly imagined style reminiscent of the popular Aztec calendars, but these two paintings eloquently illustrate the otherworldly contrasts of the militarized U.S.-Mexico border.

El Paso painter Oscar Moya juxtaposes the image of a man crawling over the green, glowing electrified wire of a border fence with that of another famous migrant, a giant Monarch butterfly. Moya paints from experience. Born in Mexico City, he crossed the border at age 15 and journeyed from San Antonio to Illinois as a migrant worker, eventually attending the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

With more than 100 works by about 25 artists from El Paso to Brownsville and including several from San Antonio, “Icons & Symbols of the Borderland,” on view through December 17, is the first touring show presented by the Department of Arts & Culture at Centro de Artes (in the Market Square space formerly known as Museo Alameda). Organized by the El Paso-based JUNTOS Art Association and curated by Diana Molina, the show debuted in 2015 at the University of Texas at El Paso Centennial Museum and traveled to Austin’s Mexic-Arte Museum last fall. Molina, who earned a computer science degree from the University of Texas at Austin, worked as a software engineer for IBM before shifting her focus to photography and journalism.

As the national political firestorm rages over border security and immigration, “Icons & Symbols” considers the shared religious beliefs, history, cuisine and environmental concerns of the people who live along both sides of the Rio Grande, and ponders what will be sacrificed if the fire-breathing, Mexico-hating leader of the free world succeeds in completely walling us off from our southern neighbors.

San Antonians used to consider the border the city’s backyard, an easy trip to an exotic land, but now it’s more like visiting the outskirts of a giant prison lined by metal fencing and razor wire. Automatic weapons fire, the whap-whap-whap of helicopters and heavily armed border patrol agents zipping around in all-terrain vehicles are now a routine part of life. Building a bigger, more imposing wall seems like overkill.

The “Frontera” section of the exhibit includes the works by Castro and Moya along with a photo collage by Molina that puts faces on the people most affected by our beefed-up border paranoia. She also documents the various types of fencing already in place along the border and notes in the wall label that the price tag is $20 million for the prototypes of President Trump’s wall currently under construction in San Diego, California, and with total cost estimates ranging from $15 billion to $75 billion — which, oddly, considering Trump’s fervent campaign promises, Mexico is not remotely likely to pay.

Inspired by the flattened perspective and simplified figures of Aztec codices, Brownsville artist Mark Clark, who lived in Corpus Christi as a child, paints simple border pleasures — fruit and paleta vendors, acrobats, vaqueros, wrestlers and other characters he observes from the balcony of the border town’s second-oldest building, dating to 1859, which he has turned into Galeria 409. Clark spent 22 years as a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and, after retiring, moved to the Valley in 2005. He’s been instrumental in helping invigorate the local art scene, but his appropriation of Aztec imagery has drawn criticism, though the paintings are bright, colorful and rather childlike. Other paintings are edgier, such as The Cycle of Violence, which transforms the Mexican drug war’s circle-of-death into the mask of the Aztec god of war, and Dance of the Three Powers, an angel, devil and skeleton battling over a drug addict’s soul.

Molina considers religion to be the most unifying force spanning the border, which she surveys in the “Sacred and Profane” section. In a photograph of a large-scale Virgin of Guadalupe tattoo on a man’s back, Delilah Montoya, who teaches at the University of Houston, tries to reintroduce the icon as a symbol of “the colonial dark side” signifying “captivity, oppression and servitude.” Describing himself as the “quintessential Chicano artist,” Gaspar Enríquez of El Paso reveals the contradictions of barrio culture tattooed on a vato’s chest in Mi Querida Madre. In a painting from 2003, Hombre que le Gustan las Mujeres, San Antonio artist César Martínez illustrates the “Madonna/whore” duality that undermines traditional machismo, showing a mustachioed muscle man with a Virgin tattooed on his left arm and a topless stripper on his right. Martínez also mocks religious and cultural authority by transforming the Virgin of Guadalupe into Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in his recent painting Mona Lupe: The Epitome of Chicano Art.

In the “Environment” section, Martínez looms large with his mural-size At Play in the Fields of César Chávez, inspired by the many streets named after the civil rights icon. In his painting of Huizache Jaguar, which vanished from South Texas in the 1940s, and his rattlesnake sculpture made with rusted barbed and baling wire, Martínez shows his respect for the region’s wildlife. But the most amazing sculptures in the show are by San Antonian Jose Rivera, whose figures and creatures carved in mesquite are stunning, not to mention the giant, bronze Chicharra. San Antonio artist Richard Armendariz flies into the mythic with his oil on carved plywood Tlazolteotl as a Horse.

Andy Villarreal of San Antonio mingles ancient Mayan mythology with contemporary pop images in his thickly painted oils, such as The Mighty Mayan Warrior Takes a Slave Peacefully in Front of the Bistro, and mixed-media on copper works, such as The Mayan Twins Meet the Leaping Jaguar.

“Icons & Symbols” is an impressive survey of Texas artists dealing with issues along the border, providing a far more nuanced perspective on the lifeways of the Rio Grande than anything you’re likely to encounter in the national media, or coming from the delusional Tweets of the Bloviator-in-Chief.

Free, 11am-6pm Tue-Sun through December 17, Centro de Artes, 101 S. Santa Rosa Ave., (210) 206-2787, getcreativesanantonio.com.

Castro, a graphic designer and children’s book illustrator, may be a tad romantic and his richly imagined style reminiscent of the popular Aztec calendars, but these two paintings eloquently illustrate the otherworldly contrasts of the militarized U.S.-Mexico border.

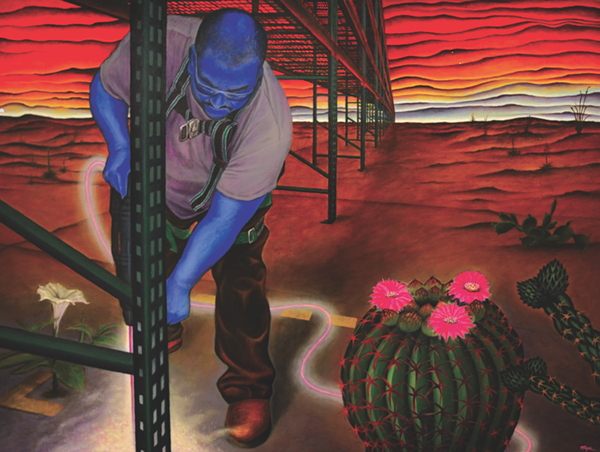

El Paso painter Oscar Moya juxtaposes the image of a man crawling over the green, glowing electrified wire of a border fence with that of another famous migrant, a giant Monarch butterfly. Moya paints from experience. Born in Mexico City, he crossed the border at age 15 and journeyed from San Antonio to Illinois as a migrant worker, eventually attending the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

With more than 100 works by about 25 artists from El Paso to Brownsville and including several from San Antonio, “Icons & Symbols of the Borderland,” on view through December 17, is the first touring show presented by the Department of Arts & Culture at Centro de Artes (in the Market Square space formerly known as Museo Alameda). Organized by the El Paso-based JUNTOS Art Association and curated by Diana Molina, the show debuted in 2015 at the University of Texas at El Paso Centennial Museum and traveled to Austin’s Mexic-Arte Museum last fall. Molina, who earned a computer science degree from the University of Texas at Austin, worked as a software engineer for IBM before shifting her focus to photography and journalism.

As the national political firestorm rages over border security and immigration, “Icons & Symbols” considers the shared religious beliefs, history, cuisine and environmental concerns of the people who live along both sides of the Rio Grande, and ponders what will be sacrificed if the fire-breathing, Mexico-hating leader of the free world succeeds in completely walling us off from our southern neighbors.

San Antonians used to consider the border the city’s backyard, an easy trip to an exotic land, but now it’s more like visiting the outskirts of a giant prison lined by metal fencing and razor wire. Automatic weapons fire, the whap-whap-whap of helicopters and heavily armed border patrol agents zipping around in all-terrain vehicles are now a routine part of life. Building a bigger, more imposing wall seems like overkill.

The “Frontera” section of the exhibit includes the works by Castro and Moya along with a photo collage by Molina that puts faces on the people most affected by our beefed-up border paranoia. She also documents the various types of fencing already in place along the border and notes in the wall label that the price tag is $20 million for the prototypes of President Trump’s wall currently under construction in San Diego, California, and with total cost estimates ranging from $15 billion to $75 billion — which, oddly, considering Trump’s fervent campaign promises, Mexico is not remotely likely to pay.

Inspired by the flattened perspective and simplified figures of Aztec codices, Brownsville artist Mark Clark, who lived in Corpus Christi as a child, paints simple border pleasures — fruit and paleta vendors, acrobats, vaqueros, wrestlers and other characters he observes from the balcony of the border town’s second-oldest building, dating to 1859, which he has turned into Galeria 409. Clark spent 22 years as a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and, after retiring, moved to the Valley in 2005. He’s been instrumental in helping invigorate the local art scene, but his appropriation of Aztec imagery has drawn criticism, though the paintings are bright, colorful and rather childlike. Other paintings are edgier, such as The Cycle of Violence, which transforms the Mexican drug war’s circle-of-death into the mask of the Aztec god of war, and Dance of the Three Powers, an angel, devil and skeleton battling over a drug addict’s soul.

Molina considers religion to be the most unifying force spanning the border, which she surveys in the “Sacred and Profane” section. In a photograph of a large-scale Virgin of Guadalupe tattoo on a man’s back, Delilah Montoya, who teaches at the University of Houston, tries to reintroduce the icon as a symbol of “the colonial dark side” signifying “captivity, oppression and servitude.” Describing himself as the “quintessential Chicano artist,” Gaspar Enríquez of El Paso reveals the contradictions of barrio culture tattooed on a vato’s chest in Mi Querida Madre. In a painting from 2003, Hombre que le Gustan las Mujeres, San Antonio artist César Martínez illustrates the “Madonna/whore” duality that undermines traditional machismo, showing a mustachioed muscle man with a Virgin tattooed on his left arm and a topless stripper on his right. Martínez also mocks religious and cultural authority by transforming the Virgin of Guadalupe into Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in his recent painting Mona Lupe: The Epitome of Chicano Art.

In the “Environment” section, Martínez looms large with his mural-size At Play in the Fields of César Chávez, inspired by the many streets named after the civil rights icon. In his painting of Huizache Jaguar, which vanished from South Texas in the 1940s, and his rattlesnake sculpture made with rusted barbed and baling wire, Martínez shows his respect for the region’s wildlife. But the most amazing sculptures in the show are by San Antonian Jose Rivera, whose figures and creatures carved in mesquite are stunning, not to mention the giant, bronze Chicharra. San Antonio artist Richard Armendariz flies into the mythic with his oil on carved plywood Tlazolteotl as a Horse.

Andy Villarreal of San Antonio mingles ancient Mayan mythology with contemporary pop images in his thickly painted oils, such as The Mighty Mayan Warrior Takes a Slave Peacefully in Front of the Bistro, and mixed-media on copper works, such as The Mayan Twins Meet the Leaping Jaguar.

“Icons & Symbols” is an impressive survey of Texas artists dealing with issues along the border, providing a far more nuanced perspective on the lifeways of the Rio Grande than anything you’re likely to encounter in the national media, or coming from the delusional Tweets of the Bloviator-in-Chief.

Free, 11am-6pm Tue-Sun through December 17, Centro de Artes, 101 S. Santa Rosa Ave., (210) 206-2787, getcreativesanantonio.com.

KEEP SA CURRENT!

Since 1986, the SA Current has served as the free, independent voice of San Antonio, and we want to keep it that way.

Becoming an SA Current Supporter for as little as $5 a month allows us to continue offering readers access to our coverage of local news, food, nightlife, events, and culture with no paywalls.

Scroll to read more Arts Stories & Interviews articles

Newsletters

Join SA Current Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.