Perhaps the most beautiful piece on Gib Wharton's 1994 album, Things I've Always Known, is the final cut, "Waltz of Life." The song is actually a musical pun; the chord progression is based on Wharton's philosophical observation that life seems to consist of "one step forward, two steps back."

When Gib wrote that composition a decade ago, he had no inkling of its prophetic nature.

One Step Forward

Gib Wharton grew up in the close-knit community of Dilley, Texas. Things came easily to him: A star athlete in high school, he made friends effortlessly. But his true passion was music. By age 12, he was playing professionally and already had a promising career ahead as a guitar and pedal steel player in country bands.

But Gib was a restless soul, never content with the status quo. He enrolled in the Southwest Guitar Academy, where he studied jazz. There he began to develop a unique voice on his instrument. He formed a power trio called Life Support, which played original music that synthesized his country roots with jazz. They opened locally for Bob James, Eric Johnson, and Spyro Gyra. In 1988, he moved to New York, where he played with avant-garde artist Laurie Anderson and Marianne Faithfull. He was featured on two of jazz singer Cassandra Wilson's albums. He toured with the Holmes Brothers for four years and recorded a solo album, Things I've Always Known. And he met Pamela Dean Kenny.

Born in New York, Pamela had lived all over the world. Her parents were visual artists, and she eventually settled on an acting career, living in Manhattan. She and Gib had much in common; each was an only child, and a creative, stubborn non-conformist with an outrageous sense of humor. They married in Dilley in September of 2000. Wedding pictures were taken in front of the giant watermelon statue in the middle of town.

In the spring of 2001, Gib and Pamela were splitting their time between New York, Florida, and Texas. Both of Gib's parents were in failing health; Pamela's mother had died recently, leaving Pamela to settle her Florida estate. Pamela's landlord was suing to evict her from her rent-controlled apartment, claiming non-residence due to her time spent in Florida.

In late April, Gib's mother called. She did not sound well, and he immediately flew to Texas. Pamela, in mid-rehearsal for a show and due in housing court, remained in New York.

Shortly after Gib arrived in Dilley, his mother slipped into a coma and died. His father's health and mental state had deteriorated to the point where he needed 24-hour supervision. Pamela flew down from New York, and they moved his father into an assisted living facility. Pamela went back to New York to deal with the landlord; Gib stayed to take care of his parents' home.

After a long period of upheaval, Gib would finally have a chance to breathe, and to mourn his mother's death.

Two Steps Back

The morning of July 17, 2001, was a typical summer day in Dilley, hot and humid. At noon, blues artist Neal Black got a phone call from Gib, who was on his way to the bank. They made plans to get together in San Antonio the next day.

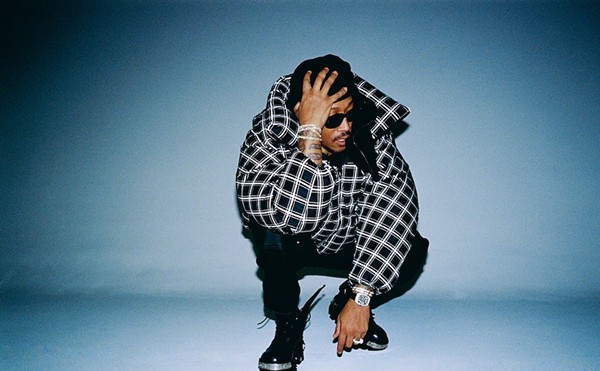

| Wharton plays pedal steel despite the loss of the fingers on his left hand. Photo by Mark Greenberg |

At five that afternoon, Pamela got a phone call in New York. There had been a bad fire. Gib was at the burn center at Brooke Army Medical Center.

"The doctor said Gib had third-degree burns on over 50 percent of his body. He was on a respirator," says Pamela, the strain still evident. "I was hearing words like 'escharotomy' and 'tracheostomy.' Then he started talking about damage to his hands. I told him they had to do everything they could to save his fingers, because he was a guitar player. The doctor said, 'At this point, we're doing everything we can just to save his life.'"

Over the next few days, details began to emerge. Apparently, Gib had returned from the bank and gone inside the house. There was a flash fire. Miraculously, he managed to drive three miles to the police station, where he was air lifted to the burn center. The police said that he'd been concerned about his dog, Zeke, who was now missing. Someone reported that Zeke had died in the fire.

When Pamela arrived in San Antonio, Black drove her straight to BAMC. "I just wanted to see him, and they kept stalling. The doctor said, 'He won't look anything like you remember.' And I just kept saying, 'Okay, okay, just let me in there.'" She had to wear a sterile "space suit," which is standard procedure for visitors to guard the burn patient from infection. "Everyone expected me to go into hysterics, but when I saw him, I was actually relieved. He was still Gib: horribly injured, yes, but still Gib. He was there. He was alive."

The next day, Black drove Pamela to Dilley. The house had literally burned to the ground; everything the Whartons owned was now a pile of ashes. They repeatedly called out for Zeke, then spied a small brown head peeking tentatively around some nearby brush. Zeke came bounding over and jumped into Pamela's arms, knocking her to the ground. They rolled in the red Dilley dirt, laughing and crying. "A true Disney moment," says Pamela.

The next few months were a nightmare of uncertainty, red tape, and paperwork for Pamela, working her way through the maze of social services (like many independent contractors, they had no insurance). It was also a time when friends, acquaintances, and strangers came through with amazing support. A fund was set up at the Dilley bank, and the community was helpful and generous. Fund-raising concerts were held in San Antonio and New York. Gib and Pamela found out they had friends they never even knew.

For Gib, the three months in intensive care were a blur: heavy sedation, morphine, multiple surgeries, and skin grafts. He developed pneumonia. It was touch and go for a while, but his condition eventually improved enough for him to be moved into a ward. For two months he endured more surgery, physical therapy, and torturous but necessary treatment.

"Every morning they'd take you into the shower and literally scrub the burned skin. It was the most horrible pain you could imagine, but they had to do it. And the physical therapists would push you until you'd cry or get totally pissed off. Then they'd give you a little break, then start over again." He laughs. "They liked me because I was creative in my language when cussing them out.

"But I've got nothing but great things to say about the people at BAMC. They saved my life."

It wasn't until Gib moved to another ward that Pamela realized just how sick he'd been. "I found out that, statistically, his chances of survival had been close to nonexistent. But we'd been soliciting prayers, good thoughts, good energy from every source available." The Catholic and Protestant churches in Dilley, a Buddhist congregation, a synagogue in New York, and numerous new-age and new-thought groups in San Antonio and elsewhere participated in his healing. "We weren't picky. We took spiritual help from wherever we could get it." They are both convinced that outpouring was instrumental in Gib's survival.

Man of Steel

It's almost a year since the fire. Pamela and Gib are living in a tiny apartment on South Presa in San Antonio. The physical, emotional, and financial challenges are ongoing. The hospital bills hit the million-dollar mark long ago.

"I'll be broke for the rest of my life," says Gib, "but, hey, I'm alive. Beats the hell out of the alternative."

"Death was never an option," Pamela says firmly.

Gib lost the greater part of all the fingers on his left hand and can no longer play guitar, but he is developing a technique for pedal steel using a steel socket over his thumb. Once again, as Goldstein says, Gib is renovating the sound, transcending the normal category of the instrument. "It's like you're starting over again, except you're not 14 years old with lots of energy. It's frustrating, but I'm gonna do it."

He's already playing gigs. "Thanks to Claude Morgan — he hauled me out to play. You can't turn back when you're up there on stage playing a gig."

I recently caught Gib at Wings, where he played with Rusty Martin. In his solos on pedal steel, the music is all there — a little tentative, perhaps, but definitely there. The music is still Gib's unique voice.

In the liner notes of Gib's solo album, New York arranger/composer/multi-instrumentalist Gil Goldstein writes about the pedal steel: "Gib has innovated and really renovated the sound of that instrument to make it adaptable to every style of music. He has transcended the normal category for that instrument, and I believe that the sky is the limit for where he will take it in the future ..."

One step forward.

Discography:

Things I've Always Known

(Dragon Lady Records, 1994)

Redneck Beatnik

(Blue Cobra Music, 1995)

www.gib_wharton.tripod.com/gibwharton