Before winding another string, Macias leans over and turns up the Frank Sinatra song on the radio so he can hear it over the whirring machine. Then he takes the final product, a pair of low E strings for a signature Macias bajo sexto, and loops them through the intricately carved bridge of the instrument resting on the workbench before him. He makes every string this way, precisely and by hand. It is just one of many steps taken along the path his own father walked as a master bajo craftsman for some 60 years. The exactness is one of the reasons why the name Macias is now synonymous with the finest bajo sextos in the world.

The exact history of the bajo sexto is unclear. Some historians say it was first brought to Mexico by the Spaniards, while others claim it evolved from the 12-string guitar in the Bajio region of Mexico sometime late in the 19th century. According to Alberto's son George, his grandfather Martin learned to make bajos from a Spaniard in Morelia in the Mexican state of Mihoacan. "I think the man was either sick or very old, but he was dying and he gave his patterns to my grandfather to keep his work alive."

| George Macias carefully shaves down the edge of an assembled bajo sexto body. Photo by Mark Greenberg |

Martin Macias left Mexico to work the rails in 1916, wound up in San Antonio and established his own instrument business in 1925. During WWII however, materials such as brass wire became scarce, and the family moved into the countryside, where they farmed and worked the migrant circuit. Alberto remembers getting booted from a tomato canning factory in the Midwest when he was 11 for being too young to work. The family moved back to San Antonio in 1949. Eventually, Alberto built his own house on the back of his father's property and worked at Nationwide Paper Co. before turning to bajo making fulltime after his father's death in 1983 at the age of 85. "My dad always thought he'd retire and get back out to the country, but he worked until the day he died. I guess I might too," muses Alberto.

Together with the three-row button accordion, the bajo sexto is the heart of conjunto music. In Spanish, the word conjunto can have three meanings: the style of music, the musician who plays it, or the group of musicians who play it. In the Macias house, the word bajo has at least as many meanings. It means history. It means family. It means commitment to hand-crafted quality.

On this Saturday morning, like hundreds of Saturdays before it, several generations of the Macias family gather in the workshop. Alberto's son George recalls visiting his grandfather's workshop as a boy, "I'd always ask him if he needed any help, and he'd think about it for a while and then say, 'Well there is a broom. You can sweep the shop.' I got a lot of the broom."

George now has his own workbench in the back of the shop. Although busy with his own roofing company he says "every weekend I'm here." His 15-year-old son Chris is here too, helping put the finishing touches on a bajo. "I like it," says the spiky-haired, soft-spoken teenager. "This was important to my grandfather and to my father and now to me. My friends think it is cool that I can make the instruments. Some of them come around here." Chris says he likes all kinds of music and gets sandwiched between his grandfather's "oldies" and his dad's "country." He also knows who's boss. "It depends. When I'm working with my grandfather, I have to do it his way and when I work with my dad, I have to do it his way."

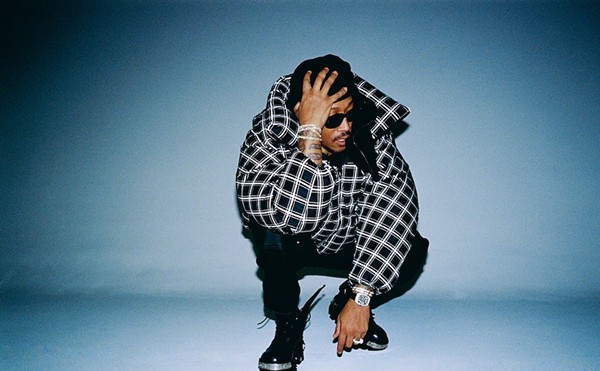

| Chris Macias looks on as his father George demonstrates the proper technique for trimming the edge of a bajo sexto body. Chris, 15, is learning the family trade several days a week after school and on weekends. Photo by Mark Greenberg |

"My dad is so busy, and a lot of people think we take too long," admits George. "But then we get all these bajos that other people made that have warped or cracked, and they want us to fix them. We take long because we do it right." During one of my visits to the shop, Alberto is working on a bajo for a California musician named Anicete Seratto. "Put his name in your article," Macias quips. "That way he won't be mad that it took so long."

Alberto Macias is now 65 and claims that he is slowing down; but in the shop, he never stops moving: shaving a spruce top, sanding a mahogany neck, winding endless strings. "All those years I'd come in to see my father before work, and I'd say, 'You know, someday I really want to learn your trade.' He'd say to me, 'When I see you standing at my bench then I'll know that you are serious. And here I am. Here I still am."

Alberto's wife, Idiana, stands in front of a wall thickly papered with images of conjunto greats who play Macias bajos. Her granddaughter Francesca pulls out a photo album. "There is Chris with the first bajo he made on his own," she says. "There is George's wife putting on the finishing coat of varnish." Idiana laughs and says, "You know some kids make mud pies. Well, ours made sawdust pies. We've set up lots of playpens back here." She speaks almost reverently of her father-in-law. "He was a great, great man. You know Alberto likes to work outside sometimes, and I tell him to be careful with his dad's patterns. They are like gold, you know, like gold."