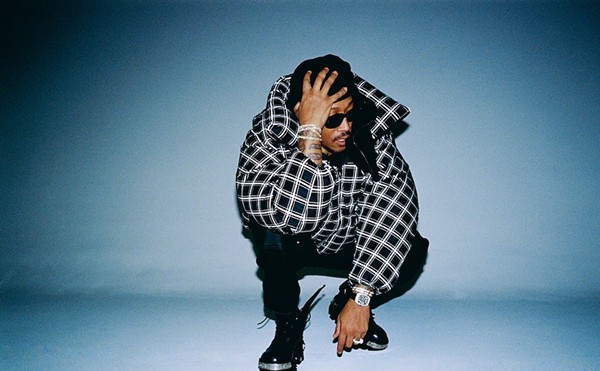

Big Sam's Funky Nation is bringing its raucous, brass-fueled funk to San Antonio as a headliner for the 40th annual Jazz'SAlive, scheduled for Sept. 29-30 in Hemisfair's Civic Park.

The New Orleans-based group is known for working from an eclectic sonic palate that includes not just the jazz and funk of its Big Easy roots but also rock, hip-hop and more. It's an accessible mix meant to get audiences up and moving as part of a communal experience.

Big Sam's Funky Nation will perform Saturday, Sept. 30. A full schedule of Jazz'SAlive performers — who also include Kirk Whalum, Jackie Venson and the Yuko Mabuchi Trio — is available at saparks.org/event/jazz-sa-live.

Bandleader and trombonist Sammie "Big Sam" Williams launched Funky Nation in 2000 after a stint with his city's revered and long-running Dirty Dozen Brass Band. He joined the Dirty Dozen at the age of 17.

In common with the Dirty Dozen, Funky Nation has collaborated with a wide variety of artists. Notably, Williams played with Elvis Costello and Allen Toussaint on their critically acclaimed The River in Reverse album and tour.

Jazz'SAlive will mark something of a homecoming for Williams, who settled in San Antonio for two years following Hurricane Katrina. Appropriately, he also had a recurring role on the HBO drama Treme, which followed New Orleans residents rebuilding after the storm.

We caught up with Williams by phone to talk about what separates New Orleans' funk from the rest of the pack, what inspired his break from the Dirty Dozen and his memories of the Alamo City.

There's a ton of bands that purport to play funk, but not everybody can get people up and moving. What's that special ingredient in your music that makes people dance?

Yeah, you're right. In my personal opinion — and professional opinion, now (laughs) — it's all about the vibe and the energy that you bring. You know what I'm saying? Overall, I like to live a positive life, and I like to bring a lot of energy and a lot of good spirits to the stage. You know what I mean? When I'm performing, I'm all about, let's have fun, let's make it about all of us and have a good time. Let's put all our words behind us and let's be in the moment and have a blast, you dig?

A lot of musicians, no matter what type of music they play, some of them make it about them and only them. And that's cool if that's your thing. ... But for what I do, and from what I notice with a lot of musicians that make people get up and dance and make them feel good, the music is about simplicity too.

You want them to be able to groove and move with you. You don't want to be doing so many things, where it's so intricate where they can't really enjoy themselves. ... But to have them focus on the music and having a good time at the same time and dancing, just dancing — "Oh, this is great. I love this song." Or "I love this music. I'm having such a blast." That's a whole other level, man.

Could you talk a little bit about the difference between New Orleans funk and what separates it from the funk people might be familiar with from elsewhere?

So, in New Orleans we add that little extra sauce with it, and that's the thing. We all take our interpretation of whatever we want to play, and we create our own musical gumbo. You dig? So, I'm a fan of different rock bands and funk bands, jazz bands, hip-hop, everything. I'm a fan of all of that, and I make it all into my own one little thing. ... I mean, I call it funk. It's a funky pot of music. You dig?

New Orleans, specifically, though, man, we play on that back beat. A lot of cats just like stick to a straightforward boom-chick, boom-chick, boom-chick. And that's cool, and that's funk — we get into that too. But in New Orleans, you go, [emulates a drum kit hitting a syncopated rhythm heavy on the backbeat.] I don't know how you're going to write that out. (Laughs.)

I was thinking that as you said it. Might be a challenge.

Right. (Laughs.) It's one of those things where we play more syncopated than a lot of other cats, and I give you that extra pep in your step when you're doing your thing. So, I would say New Orleans music and New Orleans funk is more syncopated, you know what I'm saying? If you listen to Zigaboo Modeliste from the Meters and Russell Batiste [Jr. of the Meters and others] and [New Orleans rock 'n' roll pioneer] Earl Palmers and all these cats, you see where they were coming from.

In the old school with the Mardi Gras Indians, it's all about beats. It's African beats with our New Orleans things. That big four is important on the bass drum, but the accents that we play with, it's just so different than anywhere else in the world, man. Everybody else will play it straight, but we play more syncopated and we just do our thing with it.

You up got early tutelage from saxophonist Kidd Jordan, an undisputed legend in New Orleans music. I'm wondering when you look back on that, what do you take away as the one or two most important things you learned from that exposure?

Kidd always taught me to be intentional and never be afraid of stepping outside the box. Especially coming from New Orleans, people want to put you in one box and say, "Hey, you play this type of music," or "You play this instrument, you should do this." And Kidd always taught me to be intentional, do what you want to do. Don't let anyone box you in. If you want to play country or whatever you want, you want to play folk music and you're on trombone and you want to be doing that, go ahead and do that. Just as long as you do it with great intentions. You show people, "Look, this is what I'm meant to do. I'm doing this, and you're going to love it because it's just genuine and that's what you're feeling. So, it's all going to work out."

You also performed with the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, again, a legendary New Orleans ensemble. But the impression I got was that you found that a little too confining. You wanted to break out on your own and blend more styles in with the brass.

Exactly. And here's the thing: Dirty Dozen, they were ahead of their time. Dirty Dozen back in the day, man, they were playing bebop tunes in a brass band setting, and that's what was being played on radio back in the '70s [in New Orleans]. You know what I'm saying? And when I was with them, they were still breaking boundaries, man. They were still doing their thing and pushing and pushing the envelope as far as musicians, especially from New Orleans, can do to contribute to the musical scene.

My time there, I felt like the four years that I was with them, I was kind of like, "OK, I need to keep going now." It was something that I wanted to do since I was 16 years old. Then I was 19 and playing with them — my favorite band of all time, at that point. They're the band that inspired me to start playing music in the first place. So, playing with them for those years, I was like, "OK, this is pretty cool. But, kind of like, what's next?" I wasn't content. Once I did it, I was like, "OK, cool, I'm in this now," and we're still family to this day. We say once a Dozen, always a Dozen.

So every now and then, they'll call me if they need somebody on play 'cause somebody can't make it. ... That's my people, man. Money isn't even an object, I'm there. You need me. I'm free. I'm there.

You mentioned earlier that you try to have a positive attitude. I'm guessing that played into things as well.

Oh yeah, I hope so. I was like, "Hey, got to figure out one way or another, we're going to be all right." And thing is too, we were doing 300 shows a year. We were on the road nonstop. We were doing stuff with Dave Matthews, Widespread Panic, James Brown. I mean we were rolling, man, Modest Mouse. It was a ton of bands that we were working with at the time too, and Gov't Mule. But I just had to be like, "All of this is great, but let me see what else I can do now on my own."

You've kept up that spirit of collaboration since leaving Dirty Dozen. Funky Nation's played with a lot of people as well.

Oh, yeah. And that's the beautiful thing about music, man, and it's so cool, especially in my city. We get to still travel the world and collab and get to meet some of the other cats, and people always want to work together. So, that's a plus for us. It's always a good thing to work with other people.

Do you have any memories of your time in San Antonio after Katrina?

I'll tell you what, man, it's two things actually.

One was actually meeting Buddy Miles. Buddy Miles was doing a show there. It was a restaurant, outside on the patio, and he was just looking for something to add to the show, and I got the phone call that he was looking for someone [to sit in]. ... So, I got to meet Buddy Miles, and we did a whole show together. He was trying to get me to go on the road with him and all that, but I said, "Man, I have too much going on right now. I'm really trying to do something." But Buddy Miles, that's a living legend right there, especially meeting him for the first time. He played with Hendrix and everybody, bro, so he's that dude.

But that was one of my most favorite memories of being in San Antonio. And my second one, man, was my love for Mexican food. I had no idea, man. In New Orleans, I would eat Mexican every now and then. ... Had a spot here called Not Your Mama's, it was pretty good. I'm like, "Alright, cool." Then I got to San Antonio, and the Mexican food is killing.

So, two years later, when I finally got back to New Orleans, I said, "I want some Mexican food. OK, that spot has some good food. Let me go check it out." Then I was like, "What the hell is this? Get this out of here, man, what the hell?" I started trying to find another spot and, man, I couldn't find nowhere to compare to the food out in San Antonio. I was like, this is food, yes, but it's not Mexican food. I said, "Man, I got to get back to Antonio, get me some real Mexican food." Now, though, about 27 years later, we have some better spots here in the city now, so I got my fix.

What should people be expecting when you come back to perform at Jazz'SAlive?

They can expect one hell of a party. I kind of feel like these kind of festivals, people going to have their lawn chairs out there and all — and that's cool. It might be hot outside, you might want your lawn chair for a minute, but once we hit that stage, I'm going to have you up and dancing. So get ready to shake something.

Free-$60 (special packages available), 4:30 p.m.-11 p.m. Friday, Sept. 29, and 11:00 a.m.-11 p.m. Saturday, Sept. 30, Civic Park at Hemisfair, 210 S. Alamo St., (210) 709-4750, saparks.org/event/jazz-sa-live.

Subscribe to SA Current newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter| Or sign up for our RSS Feed