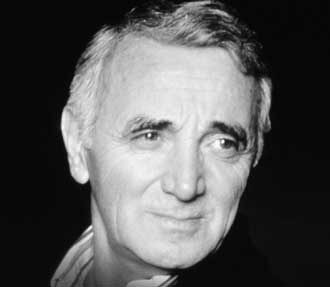

| Charles Aznavour |

That Charlie appearance was so winning that, without knowing his work all that well, I jumped at the chance to see Aznavour in concert last month in Toronto. He had decided to go on a farewell tour (he’s done this before, but this time he may mean it), although it’s a peculiar sort of goodbye: A bit-by-bit abdication, as he described it to a reporter for the Toronto Star. “I am saying goodbye to all the parts of the world where I sing in different languages. I have already done the German countries. The English-speaking ones are next, then the Spanish, then the Japanese.” His followers in France, so far, need not fear his disappearance.

In a city with plenty of Francophones, Aznavour had little trouble selling every seat in the enormous Hummingbird Centre for the Arts. The crowd ranged from well-groomed retirees to, unexpectedly, pairs of 20-ish women who clearly knew many of his songs by heart. On the way in, I was confronted by the breadth of his repertoire: Sitting contentedly alongside the many individual records and souvenir booklets at the merchandise table was a Complete Recordings box set — 44 CDs, housed in a comically pompous two-foot-tall model of Paris’s Arc de Triomphe. (I believe the price tag was just over $1,400.)

When he took the stage, it was easy to understand what drew the crowd. However self-conscious he may have been early on about his height, Aznavour has acquired a master entertainer’s comfort with his body. In a shiny black dinner jacket and open-necked black shirt, he was debonair despite the fact that his art relies so much on vulnerability. With expressive but restrained body language, he made listeners feel they were in a much smaller venue.

The evening’s arrangements, unfortunately for me, weren’t quite as evocative of the small cafés where French chanson first flourished. More reminiscent of a late ’70s or early ’80s Sinatra gala, they flowed like syrup off the stage. The band of more than a dozen players included strings and acoustic instruments, but relied far too heavily on a standard drum kit, electric bass, and (somewhat strangely in a group that already had a piano, violins, and most other things keyboards generally substitute for in these settings) a synthesizer. Only in rare moments did Aznavour cut his sidemen free, singing a number accompanied only by his own piano playing.

The songs themselves, though, had an appeal that survived the instrumentation. Full of romanticized regrets and soaked in wine, many of them are so effective in picturing a man near the end of life’s road that you wonder how he put them across when he was (as with “Yesterday When I Was Young”) barely 40. Jean Cocteau once suggested that Aznavour made despair popular, and as a young woman joined him to sing a mid-set duet, he was clearly one of those men who only become more attractive in resignation. (The song pictured an aged man and a girl on a park bench. “The young girl is traveling out into her future,” he explained wistfully, “and the old man, into his past.”)

But after crowd-pleasers such as “She” (made popular by Elvis Costello in the film Notting Hill) and “I Could Never Forget,” the crooner — still in remarkable voice, easily emoting in cognac-like tones over the hubub behind him — showed a side his English-speaking fans may not have known. In France, Aznavour has made waves from time to time by singing about politics, war, and homosexuality. Here, he presented a recent composition, “The Living Dead,” inspired by the plight of journalists taken hostage in Iraq. He sang it in French, but translated the raw lyrics beforehand: “I crawl in blood, dirt, and shit,” he intoned, and the bittersweet theatrics of his sad-old-man routine were replaced by an obviously heartfelt admiration for those who risk their lives trying to tell the truth.

That detour didn’t last long, but the crowd received it enthusiastically. Cathartic despair, it seems, works for more topics than just lost love.